Liver cancer is one of the deadliest cancers on Earth, not because it grows fast but because it spreads silently. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form, often metastasizes before it is detected. For years, scientists have tried to answer a crucial question: what fuels this leap from a confined tumor to a roaming, lethal disease? Chinese researchers have now uncovered one of the hidden mechanisms — and it begins not inside the cancer cell itself, but in the immune cells that are supposed to defend the body.

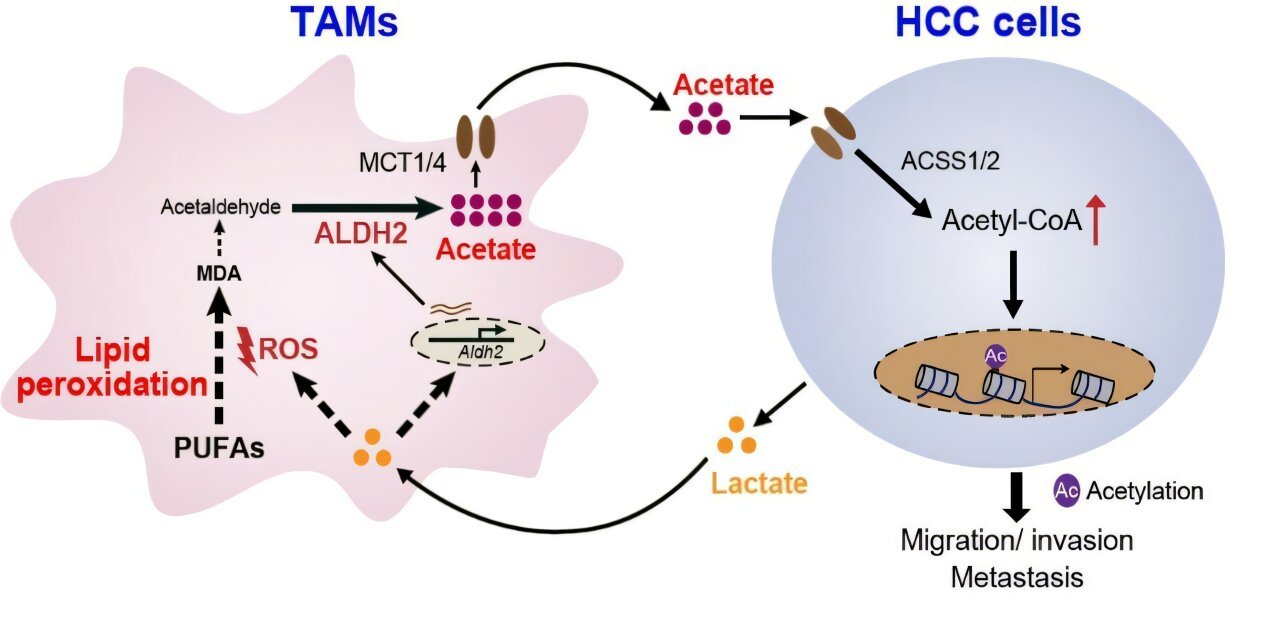

Inside a tumor, immune cells are not always enemies. Many of them are coerced into becoming accomplices. The study, led by Dr. Lu Ming of the Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health and published in Nature Metabolism, reveals how HCC hijacks tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and forces them to manufacture acetate, a metabolic fuel that accelerates metastasis. The finding does not just identify the source of acetate inside tumors — it exposes a chain of chemical persuasion that turns defenders into suppliers.

A Small Molecule With Outsized Consequences

Acetate may sound humble — a simple, small carbon molecule familiar even from vinegar — but inside a cancer ecosystem it becomes a strategic weapon. Once absorbed by cancer cells, acetate is converted into acetyl-CoA, one of the most central molecules in biology. Acetyl-CoA feeds the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, drives lipid synthesis, and, importantly, directs epigenetic control through histone acetylation. Metastatic cancers characteristically generate more acetyl-CoA — in effect rewriting their own identity to become more mobile, more invasive, and more resistant.

Previous clues hinted that acetate inside tumors is higher than in the bloodstream, meaning it must be locally produced rather than imported. But which cells were producing it, and under whose instruction, remained a mystery. The new work answers both questions: TAMs are the suppliers, and cancer cells are the instigators.

The Metabolic Conversation Inside a Tumor

The study shows that HCC cells do not passively coexist with macrophages — they chemically educate them. Cancer cells release lactate, a by-product of their warped metabolism. This lactate infiltrates TAMs and elevates reactive oxygen species (ROS), triggering a chain reaction known as lipid peroxidation. In response, TAMs activate the enzyme ALDH2 to detoxify the peroxidation products — and in that detoxification step, acetate is generated as a final product and secreted back into the microenvironment.

The tumor then reabsorbs the acetate and converts it into acetyl-CoA. The acetyl-CoA fuels histone H3 acetylation and drives the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the process through which stationary cells transform into migratory invaders. In essence, cancer cells outsource the production of metastasis-fuel to hijacked immune cells.

Proof in Mice, Proof in Cells, and a Point of Vulnerability

The discovery was not a speculative inference but demonstrated across models. In mice implanted with liver tumors, depleting TAMs sharply reduced acetate levels inside HCC cells. When ALDH2 was genetically knocked out in TAMs, lung metastases dropped significantly. In cultured systems, blocking either lipid peroxidation or ALDH2 stopped acetate-driven migration of cancer cells.

This is more than an elegant map — it is a therapeutic opening. Drugs that target ALDH2 in TAMs, or interfere with lipid peroxidation upstream, could cut off one of the metabolic engines of metastasis without directly assaulting the cancer cells themselves. That strategy matters, because cancer cells mutate relentlessly, but their enablers — such as TAMs — are genetically stable and easier to drug without breeding resistance.

A Tumor Is Not Just a Mass — It Is an Ecosystem

The significance of this research lies in how it reframes metastasis. Spread is not simply the property of a rogue cell becoming more aggressive. It is the product of a metabolic network — a communication loop in which cancer cells rewrite the behavior of neighboring cells to build their own launchpad. The tumor microenvironment is not a backdrop but an active partner in disease.

By exposing a precise biochemical axis — lactate from tumor to macrophage, ALDH2-mediated acetate out of macrophage, acetyl-CoA and histone acetylation back into tumor — the study replaces speculation with mechanism. And mechanism is what allows medicine to intervene.

Toward a Future With Smarter Interventions

This work adds to a growing realization: cancer is not just a genetic illness but a metabolic and ecological one. Targeting enzymes like ALDH2 in the right cell type at the right layer of the tumor ecosystem may slow spreading without needing to eradicate every malignant cell. For a disease where metastasis is the true killer, this shift in target could be profound.

The discovery also carries a subtler emotional weight. Our immune cells are designed to protect us, yet cancer can draft them into service through pure chemistry. But the same logic that explains betrayal makes intervention possible: if a conversation can be hijacked, it can also be interrupted. Blocking a single enzyme in the right cell might mean the difference between a contained tumor and a fatal metastasis.

In peeling back the layers of this malignant economy — who supplies what, under whose orders, and to what end — this study does more than document a process. It gives clinicians a new handle on one of cancer’s darkest tricks, and with it, a new reason to believe that even the most stubborn malignancies carry within them exploitable weaknesses.

More information: Li Shen et al, Tumour-associated macrophages serve as an acetate reservoir to drive hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis, Nature Metabolism (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s42255-025-01393-9