A new study published in The BMJ suggests that the human body does not easily forget what is eaten in the earliest chapter of life. In a natural experiment made possible by a historical event — the end of UK sugar rationing in 1953 — researchers found that people whose sugar intake was restricted from the womb into toddlerhood grew into adults with significantly lower risks of heart disease, heart attack, stroke, and heart failure. The finding is striking not only for what it reveals about nutrition but also for how early the heart’s fate can be influenced: before a person even takes their first breath.

A Historical Quirk Becomes a Scientific Window

After World War II, the United Kingdom continued to ration sugar for years to stabilize supply. That policy ended abruptly in September 1953. This one-time national shift created a rare opportunity for scientists decades later: two large groups of people born just before and just after the lifting of rationing, similar in many respects except for what they consumed in early life.

Drawing on data from 63,433 adults in the UK Biobank — all born between 1951 and 1956 and free of heart disease at enrollment — researchers compared those who lived under sugar rationing in early development with those who did not. About 40,000 were exposed to rationing during gestation or infancy; about 23,000 were not. The investigators then followed their medical histories over time to see how frequently major cardiovascular events appeared in each group.

The differences were not subtle.

The First Thousand Days Leave a Cardiovascular Footprint

Participants whose sugar intake was restricted from conception to about age two were dramatically less likely to develop heart disease in adulthood. Compared with those who never lived under rationing, this group showed:

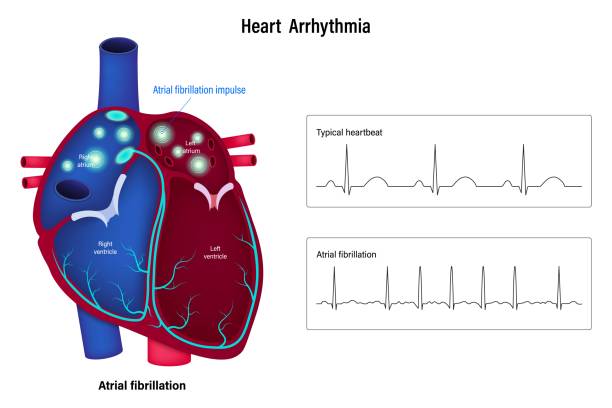

— 20% lower risk of overall cardiovascular disease

— 25% lower risk of heart attack

— 26% lower risk of heart failure

— 31% lower risk of stroke

— 27% lower risk of cardiovascular death

Even more striking, the onset of disease — when illness did occur — was delayed by up to two and a half years. That extra time is not trivial: in population health terms, it can translate to more years lived without disability, lower medical costs, and extended independence in aging.

The benefits were not mysterious. Much of the protection appeared to be mediated through lower rates of diabetes and high blood pressure in adulthood — two powerful drivers of heart disease that themselves often have dietary origins.

Why the Earliest Diet Matters So Deeply

The first thousand days of life — from conception to roughly age two — are a period of intense biological programming. During this window, organs are still forming, metabolic systems are being calibrated, and the body is learning what “normal” intake looks like. When sugar is heavily restricted in this window, the body may establish healthier set points for insulin response, blood pressure regulation, and fat storage. When excess sugar floods development, those same systems may be imprinted toward disease.

The rationing rules at the time are noteworthy when compared to today’s dietary turmoil. Daily sugar was capped below 40 grams for everyone — and babies under two were not permitted any added sugar at all. Those constraints are not far from the modern pediatric guidelines urging parents to avoid sugary drinks and ultra-processed foods during infancy and toddlerhood.

Policy, Not Willpower, Made the Difference

It is important that the health benefits revealed in the study did not emerge from personal choice or disciplined parenting. They came from policy. The environment itself reduced exposure. No single household needed heroic restraint; the guardrail was structural.

That matters for how this research should be read in the present. Modern families are immersed in an environment saturated with sugar and engineered foods. Expecting individual parents to outperform the food landscape ignores how much early health depends on conditions beyond personal control. What the UK’s rationing years show is that population-level nutrition policy — even one created for reasons unrelated to health — can leave a protective imprint across a lifetime.

Limits, Caveats, and What Still Isn’t Known

Like all observational studies, this one does not prove that sugar restriction directly causes lower heart risk. It cannot reconstruct exact infant diets from seventy years ago. Some confounders may persist despite adjustment. But the study’s design — especially the use of an external comparison group of adults born abroad — strengthens the inference that the rationing environment itself influenced cardiovascular outcomes.

The authors do not treat their findings as the last word. They argue that future work should follow individuals with precise dietary records, incorporate genetics and lifestyle interactions, and translate these population insights into personalized prevention strategies.

A Lesson With Future Consequences

If the results hold, their implication is powerful: heart disease — long assumed to be shaped mostly by middle-age lifestyle — may in part be prevented decades earlier than anyone typically intervenes. Sugar habits before memory begins may alter the probability of heart failure in a person’s sixties.

That possibility carries emotional and ethical weight. A society that protects developing bodies from excessive sugar is not denying pleasure; it may be postponing illness. The infants who could not taste sweetness in 1952 unknowingly inherited a quieter heart half a century later. The costs of rationing were felt immediately. The benefits were invisible until adulthood.

Public health rarely gives such long echoes, but this one does: the heart does not forget the appetite of infancy.

More information: Exposure to sugar rationing in first 1000 days after conception and long term cardiovascular outcomes: natural experiment study, The BMJ (2025). DOI: 10.1136/bmj-2024-083890