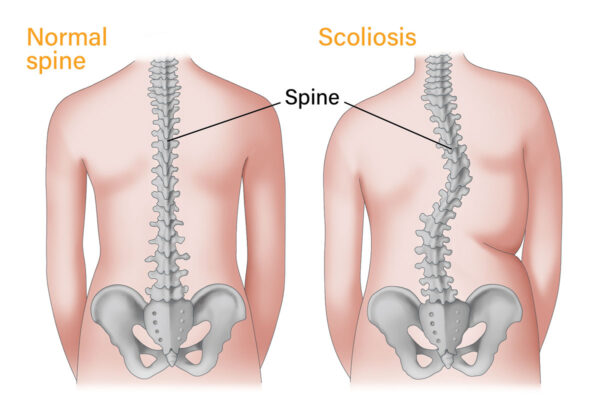

Beneath the skin and muscle of the back lies one of the most elegant and complex structures in the human body—the spine. It is our central support column, the architectural marvel that allows us to walk upright, bend with grace, and carry the burdens of life, both literal and metaphorical. Yet this intricate structure is not immune to error. Sometimes, for reasons still not fully understood, the spine begins to twist and curve in ways it was never meant to. This condition is known as scoliosis.

Scoliosis, from the Greek word skolios, meaning “crooked,” describes a sideways curvature of the spine that occurs most often during the growth spurt just before puberty. Unlike the natural curves that help the spine absorb shock and maintain balance—the gentle S-shape when viewed from the side—scoliosis manifests as a lateral deviation when viewed from behind. The spine may curve in a C-shape or S-shape, with the vertebrae often rotating in addition to shifting laterally. This rotational element is what distinguishes scoliosis from mere postural abnormalities and makes it such a unique orthopedic puzzle.

When the Backbone Becomes a Question Mark

Scoliosis does not announce itself loudly. It can creep into a child’s body quietly, sometimes only noticed when a parent sees a shoulder blade protruding unevenly or when clothes begin to hang awkwardly. The most common form, idiopathic scoliosis, bears a name that betrays our ignorance—idiopathic meaning “of unknown cause.” It accounts for about 80 percent of scoliosis cases and typically appears in children between the ages of 10 and 18. Girls are more likely than boys to develop more severe curvatures that require treatment.

This silence, this lack of early pain or discomfort, can be misleading. Many children with scoliosis feel perfectly fine, even as their spine begins to form exaggerated curves that, if left unchecked, may cause long-term complications. It is a condition where the body seems to betray its own symmetry, where the axis that once stood straight now draws a distorted question mark through the torso. That silent asymmetry is not just physical—it can affect posture, body image, and self-esteem, especially during the sensitive years of adolescence.

The Many Faces of a Crooked Spine

Scoliosis is not a single disease but a spectrum of disorders with various causes and manifestations. Beyond idiopathic cases, other forms of scoliosis include congenital, neuromuscular, degenerative, and syndromic types. Congenital scoliosis arises from abnormal vertebral development in the womb, leading to spinal malformations that are present at birth. These structural anomalies—such as hemivertebrae, where only half of a vertebra forms—can lead to uneven growth and dramatic curvatures.

Neuromuscular scoliosis occurs as a secondary complication of conditions like cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, or spinal cord injury. In these cases, muscle weakness or imbalance fails to support the spine properly, allowing gravity to pull it into abnormal shapes. Syndromic scoliosis is associated with systemic diseases like Marfan syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, where connective tissue abnormalities contribute to spinal instability.

Even in older adults, the spine can begin to curve anew. Degenerative scoliosis, also called adult-onset scoliosis, often develops due to age-related changes in the spine—intervertebral disc degeneration, osteoporosis, or arthritis can lead to an imbalance in spinal mechanics. These cases, while different in origin from adolescent scoliosis, may share similar symptoms: back pain, stiffness, and limited mobility.

Anatomy of a Curve and the Mechanics of Misalignment

To understand how scoliosis progresses, one must first understand the anatomy of the spine. The human spine is made up of 33 vertebrae divided into five regions: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal. Each vertebra is separated by intervertebral discs that act as shock absorbers. The entire structure is supported and stabilized by ligaments and muscles that allow movement while maintaining alignment.

In scoliosis, the curvature often begins subtly. The thoracic region, which encompasses the upper and mid-back, is the most commonly affected area. However, curves can also occur in the lumbar spine or span both regions. As the curvature increases, it exerts mechanical stress on adjacent vertebrae and soft tissues. The muscles on the convex (outer) side of the curve may become overstretched, while those on the concave (inner) side may contract and tighten. This muscular imbalance can perpetuate the curvature, creating a feedback loop that worsens over time.

The vertebrae themselves often rotate along the axis of the curve, causing one side of the rib cage to protrude more prominently. This is known as a rib hump and is a hallmark sign observed during physical exams, especially when a person bends forward. The more the spine curves and rotates, the more it can affect surrounding structures—compressing lungs, crowding abdominal organs, and altering posture.

How Growth Accelerates the Spiral

The progression of scoliosis is intimately tied to growth. During the adolescent growth spurt, the spine elongates rapidly. In individuals predisposed to scoliosis, this period becomes a window of vulnerability. If a curve is present when growth accelerates, it can magnify dramatically within a matter of months. That’s why early detection is so critical. What begins as a mild 10-degree curve can, if unchecked, progress into a deformity greater than 40 degrees—often the threshold at which surgery becomes a consideration.

The magnitude of a curve is measured in degrees using the Cobb angle, calculated from spinal radiographs. A Cobb angle less than 10 degrees is generally not considered scoliosis. Between 10 and 25 degrees, most cases are monitored. From 25 to 45 degrees, bracing is often recommended for growing adolescents to prevent further curvature. Beyond 45 or 50 degrees, surgery may be necessary, especially if the curve continues to worsen.

Growth is a double-edged sword. While it allows the body to reach adult form, it also fans the flames of asymmetry in those with spinal curvature. As a result, managing scoliosis often becomes a race against time—a matter of catching the curve before the spine grows too far out of line.

The Psychological Weight of a Crooked Frame

For adolescents, scoliosis is more than a skeletal disorder. It is a visual and emotional disruption that can cast long shadows over self-image and confidence. Teenagers with scoliosis may feel self-conscious about the way their back looks, especially if the curve is visible through clothing or if a brace is required. While most children do not experience physical pain from scoliosis, the emotional toll can be significant.

Studies have shown that adolescents with scoliosis are more prone to anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal, especially when bracing is involved. Braces, though life-altering in their potential to prevent surgery, can be uncomfortable and stigmatizing. They must often be worn for 18 to 23 hours a day, and the bulkiness of the device can interfere with daily activities.

Surgical intervention also carries emotional weight. While spinal fusion surgery can correct severe curves and prevent future progression, the scars and limitations—both temporary and permanent—require a deep well of resilience. It’s important to recognize scoliosis not just as an orthopedic concern but as a holistic condition that touches the mind as much as the spine.

Diagnosing the Silent Curve

Diagnosing scoliosis involves a combination of physical exams and imaging. The Adam’s Forward Bend Test is a simple but effective screening method. During this test, the patient bends forward at the waist with arms hanging, allowing a physician to observe asymmetries in the back—particularly a rib hump or uneven shoulders. A scoliometer, a small device that measures the angle of trunk rotation, can provide a more precise assessment.

If scoliosis is suspected, an X-ray is taken to visualize the spine and measure the Cobb angle. In some cases, an MRI or CT scan may be ordered, especially if there are neurological symptoms or concerns about congenital abnormalities. These imaging techniques offer a clearer view of spinal anatomy and help guide treatment decisions.

Diagnosis is not just about identifying the curve—it’s about understanding its type, severity, and potential for progression. Each case of scoliosis is unique, requiring personalized evaluation and management. A ten-degree curve in a ten-year-old is not the same as a similar curve in a seventeen-year-old. The younger the patient and the more growth remaining, the higher the risk of progression.

Bracing the Curve with Hope and Plastic

For many adolescents with moderate scoliosis, bracing is the frontline defense. Modern braces are vastly improved from the heavy, uncomfortable contraptions of the past. Today’s thoracolumbosacral orthoses (TLSO) are made from lightweight plastic, molded to fit the contours of the body. Though still restrictive, these braces are designed for discretion and mobility.

The goal of bracing is not to straighten the spine completely, but to halt further progression. By exerting pressure on the outer curve and supporting the inner one, the brace guides the spine to grow more symmetrically. It must be worn consistently—typically for most of the day and night until the child stops growing. Success depends on compliance, curve flexibility, and early intervention.

Bracing is not a cure, but it is a powerful tool. When used appropriately, it can reduce the likelihood of surgery by more than 70 percent. For families navigating the uncertainty of scoliosis, a brace can be both a physical intervention and a symbol of control—a way to actively shape the future of a growing spine.

When Steel and Bone Must Fuse

In severe cases, when curves exceed 45 to 50 degrees or continue to progress despite bracing, surgery may be necessary. The most common procedure is spinal fusion, in which the curved portion of the spine is straightened as much as safely possible and then fused together using bone grafts and metal rods. Over time, the vertebrae grow into a single solid bone, preventing further curvature.

Spinal fusion is a major surgery, but it has a high success rate and can dramatically improve spinal alignment and quality of life. Recovery typically involves a hospital stay, followed by months of limited activity and physical therapy. Advances in surgical technique and instrumentation have made the procedure safer and more effective, with reduced recovery times and better long-term outcomes.

For adults with degenerative scoliosis, surgery is more complex due to existing spinal wear, reduced bone density, and comorbidities. In these cases, the decision to operate is often based on pain, neurological symptoms, and functional impairment rather than curvature alone.

Life After Scoliosis and the Resilience of the Human Frame

Scoliosis does not end with a brace or a surgery. It becomes a part of one’s story, a thread woven into the fabric of identity. Many people with scoliosis go on to lead active, fulfilling lives—playing sports, having children, building careers. For some, the condition becomes a source of strength, a challenge that forged resilience and empathy.

Long-term outcomes vary. Some individuals experience chronic back pain, especially if the curve was not treated or progresses in adulthood. Others may develop compensatory curves or muscular imbalances that require ongoing physical therapy. Regular follow-up, exercise, and posture awareness become essential tools for maintaining spinal health.

Advances in research are shedding new light on the genetic and biomechanical underpinnings of scoliosis. Studies suggest that certain genes may predispose individuals to curvature, while newer imaging techniques are improving early detection. The future may bring personalized medicine approaches, more effective braces, and even non-surgical interventions that reshape the landscape of treatment.

Rediscovering Balance in an Asymmetric World

Scoliosis is, in essence, a deviation from symmetry. But perhaps it is also a lesson in the beauty of imperfection. The human spine, with its curves and twists, is a symbol of adaptability. It reminds us that strength is not always found in straight lines but often in the capacity to bend and still carry weight, to shift under pressure without breaking.

In telling the story of scoliosis, we tell the story of the body’s quiet battles and bold adaptations. We trace not just the curvature of vertebrae but the resilience of those who live with it. In every brace worn, in every surgical scar, in every adolescent who walks taller despite the odds, there is evidence that a crooked spine can support an upright life.