Imagine living with a constant burning in your stomach, a gnawing pain that worsens when you’re hungry or late at night, and sometimes eases for a while after a meal. For millions of people around the world, this is the lived reality of peptic ulcer disease (PUD). More than just a medical condition, it is a disorder that can disrupt daily life, impact nutrition, affect emotional well-being, and, if left untreated, lead to dangerous complications.

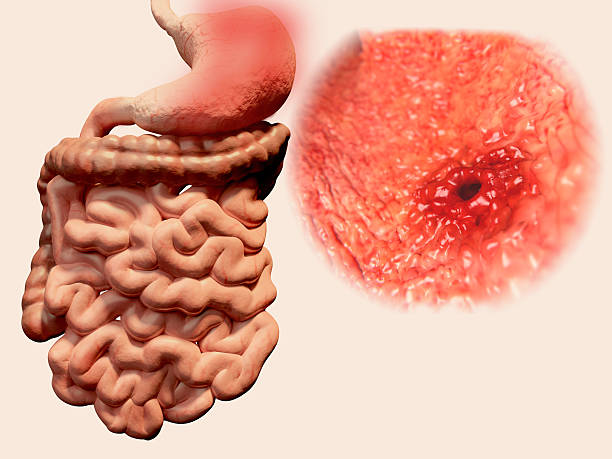

At its core, peptic ulcer disease refers to open sores that develop on the inner lining of the stomach, the upper portion of the small intestine (duodenum), or occasionally the esophagus. These sores occur when the protective barrier of mucus that normally shields the lining from stomach acid is compromised. What follows is a painful interaction: the highly acidic digestive juices, designed to break down food, instead erode the body’s own tissues.

The story of peptic ulcers is both ancient and modern. For centuries, ulcers were thought to be the inevitable result of stress, spicy foods, and a “nervous stomach.” Then, in the 1980s, two Australian scientists, Dr. Barry Marshall and Dr. Robin Warren, discovered that a bacterium—Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)—was a leading culprit. Their groundbreaking work, which won them the Nobel Prize, transformed the way we understand and treat peptic ulcers. Today, we know that ulcers are the product of a complex interplay between infection, lifestyle, medications, and physiological vulnerabilities.

To truly grasp the impact of peptic ulcer disease, we must explore its causes, recognize its symptoms, understand how it is diagnosed, and appreciate the diverse approaches to treatment that restore both comfort and health.

The Anatomy of an Ulcer

To understand how peptic ulcers form, it helps to visualize the digestive tract as a dynamic environment. The stomach produces hydrochloric acid and an enzyme called pepsin to digest food. This acidic mixture is powerful—strong enough to break down proteins and even corrode metal if left unchecked. To protect itself, the stomach and duodenum are lined with a thick layer of mucus and bicarbonate that neutralize excess acid and act as a physical barrier.

When this balance between “offense” (acid and pepsin) and “defense” (mucus and bicarbonate) is disturbed, the lining becomes vulnerable. Acid can then dig into the tissue, creating an open sore. If this sore develops in the stomach, it is called a gastric ulcer. If it develops in the duodenum, it is a duodenal ulcer.

Though both fall under the umbrella of peptic ulcer disease, duodenal ulcers are generally more common, especially in younger individuals, while gastric ulcers tend to occur more in older adults.

Causes of Peptic Ulcer Disease

The development of peptic ulcers is rarely the result of one single factor. Instead, it emerges from an interplay of biological, environmental, and lifestyle influences.

Helicobacter pylori Infection

Discovered in the 1980s, H. pylori is a spiral-shaped bacterium uniquely adapted to survive in the harsh acidic environment of the stomach. It burrows into the protective mucus layer and releases enzymes and toxins that weaken this barrier, allowing acid to damage the lining beneath.

H. pylori infection is astonishingly common, affecting more than half of the world’s population. However, not everyone with the bacterium develops ulcers. Genetics, immune response, and environmental conditions determine who will experience symptomatic disease.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Medications such as ibuprofen, aspirin, and naproxen are widely used for pain relief, but their prolonged use can erode the protective lining of the stomach and duodenum. NSAIDs inhibit enzymes (COX-1 and COX-2) that normally promote the production of prostaglandins—substances that help maintain the mucus barrier and regulate blood flow in the stomach lining. Without this protection, the risk of ulcers rises dramatically.

NSAID-induced ulcers are particularly dangerous because they may occur without obvious symptoms until complications, such as bleeding, appear.

Excess Acid Production

Certain conditions can lead to excessive acid secretion, tipping the delicate balance in favor of tissue damage. One rare but notable condition is Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, in which tumors called gastrinomas release excessive amounts of gastrin, stimulating the stomach to produce enormous quantities of acid.

Lifestyle and Risk Factors

While once thought to be direct causes, lifestyle factors like stress, alcohol consumption, and diet are now recognized as contributors rather than sole culprits. They can exacerbate existing vulnerability by:

- Increasing acid secretion

- Slowing healing of the stomach lining

- Weakening the body’s defenses against H. pylori infection

Cigarette smoking, for example, not only increases acid production but also interferes with ulcer healing and doubles the risk of recurrence. Excessive alcohol use irritates and erodes the mucosal lining, compounding the effect of acid.

Genetics and Family History

Ulcers tend to cluster in families, suggesting a genetic predisposition. Certain blood types, particularly type O, have been associated with higher rates of duodenal ulcers.

Symptoms of Peptic Ulcer Disease

The hallmark symptom of a peptic ulcer is abdominal pain, but the presentation is far more varied and complex than a single complaint. Symptoms can range from subtle to severe, and some individuals may not experience pain at all.

Typical Symptoms

- Burning or gnawing abdominal pain: Often located between the breastbone and the navel. Duodenal ulcers typically cause pain when the stomach is empty (between meals, at night), while gastric ulcers may hurt during or after eating.

- Relief with eating or antacids: Food and antacids can temporarily neutralize acid, reducing discomfort in duodenal ulcers.

- Bloating, belching, and nausea: These non-specific symptoms often accompany the pain.

- Loss of appetite or weight loss: Particularly common with gastric ulcers, where eating may trigger discomfort.

Silent Ulcers

Not all ulcers announce themselves loudly. Some remain “silent” until they cause serious complications like bleeding or perforation. Silent ulcers are more common in older adults and in people taking NSAIDs.

Complications and Warning Signs

When ulcers are left untreated, they can lead to potentially life-threatening complications. Warning signs include:

- Vomiting blood (which may appear red or like coffee grounds)

- Black, tarry stools (a sign of gastrointestinal bleeding)

- Sudden, severe abdominal pain (suggesting perforation, where the ulcer creates a hole through the stomach wall)

- Unexplained weight loss or persistent vomiting

Such symptoms require immediate medical attention.

Diagnosis of Peptic Ulcer Disease

Accurate diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease is crucial, not only to confirm the presence of ulcers but also to identify underlying causes and rule out more serious conditions such as gastric cancer.

Medical History and Physical Examination

Doctors begin by taking a detailed history of symptoms, medication use (especially NSAIDs), lifestyle factors, and family history. They may also perform a physical exam, though this often provides limited clues beyond tenderness in the abdomen.

Endoscopy

The gold standard for diagnosing peptic ulcers is an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy. A flexible tube with a camera is inserted through the mouth into the stomach and duodenum, allowing direct visualization of the ulcer. Endoscopy not only confirms the diagnosis but also enables biopsies to test for H. pylori and rule out malignancy.

Tests for H. pylori

Since H. pylori is a major cause of ulcers, detecting it is central to diagnosis. Common tests include:

- Urea breath test: Patients drink a solution containing urea; if H. pylori is present, it breaks down the urea, releasing detectable carbon dioxide.

- Stool antigen test: Detects H. pylori proteins in stool samples.

- Blood antibody test: Indicates past or present infection, though less useful for determining active cases.

Imaging Studies

In certain cases, imaging studies such as an upper GI series (barium swallow) may be used. However, endoscopy remains superior for direct visualization and biopsy.

Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease

The treatment of peptic ulcer disease has been revolutionized in recent decades. Once managed primarily with surgery or long-term acid suppression, today most ulcers can be cured with targeted therapies.

Eradicating H. pylori

When H. pylori is present, treatment focuses on eradication. The standard approach involves combination therapy, often called “triple therapy”:

- Two antibiotics (such as clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole)

- A proton pump inhibitor (PPI) to reduce acid and promote healing

This regimen, usually taken for 10–14 days, can cure the infection in the majority of cases. If resistance is an issue, alternative combinations or longer courses may be used.

Reducing Acid Production

Acid suppression is central to ulcer healing. Two main classes of medications are used:

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Such as omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole. These drugs block acid production at its source and are highly effective in promoting healing.

- H2-receptor antagonists: Such as ranitidine and famotidine, which reduce acid secretion by blocking histamine receptors in the stomach.

Protecting the Stomach Lining

In some cases, additional medications are used to enhance mucosal defenses:

- Sucralfate, which coats ulcers and protects them from acid.

- Misoprostol, particularly useful in preventing NSAID-induced ulcers, as it mimics protective prostaglandins.

Addressing NSAID Use

If NSAIDs are the culprit, discontinuing or reducing their use is essential. When necessary, safer alternatives or protective medications may be prescribed.

Surgery: Rare but Sometimes Necessary

Before the discovery of H. pylori’s role, surgery was a common treatment for ulcers. Today, it is reserved for complications such as perforation, uncontrolled bleeding, or when ulcers fail to heal with medical therapy.

Living with Peptic Ulcer Disease

Treatment does not end with medication. Managing peptic ulcer disease also involves lifestyle adjustments and long-term vigilance.

- Avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol helps reduce recurrence.

- Eating smaller, more frequent meals can ease symptoms.

- Managing stress through relaxation techniques or therapy supports overall well-being, even if it is not a direct cause of ulcers.

- Regular follow-up with healthcare providers ensures healing and detects any complications early.

The Emotional Impact of Ulcers

Living with a chronic or recurrent ulcer can be emotionally draining. The unpredictable pain, dietary restrictions, and fear of complications often create anxiety. Many patients report disrupted sleep, difficulty concentrating, or feelings of isolation. Recognizing and addressing the emotional dimension of peptic ulcer disease is crucial. Counseling, support groups, and open conversations with healthcare providers can help restore not just physical health but also emotional balance.

The Global Burden of Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcer disease is not confined to one region or socioeconomic class—it affects people worldwide. In developing countries, H. pylori infection remains highly prevalent due to crowded living conditions and limited sanitation. In industrialized nations, NSAID use and aging populations drive much of the disease burden.

The economic cost is substantial, encompassing not only medical expenses but also lost productivity and reduced quality of life. Yet, because effective treatments exist, peptic ulcer disease is also one of the most preventable and curable digestive conditions.

Looking Toward the Future

Research continues to expand our understanding of peptic ulcer disease. Scientists are developing vaccines against H. pylori, exploring new antibiotics to overcome resistance, and refining diagnostic tools for faster, more accurate detection. Precision medicine, which tailors treatment to an individual’s genetic and microbiome profile, may one day optimize ulcer therapy even further.

The broader lesson from peptic ulcer disease is profound: it reminds us that medical paradigms can shift dramatically. What was once considered a psychosomatic condition turned out to have an infectious cause. This discovery reshaped not only ulcer treatment but also our understanding of the relationship between microbes and chronic disease.

Conclusion: Healing Beyond the Ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease is more than just a sore in the stomach or intestine. It is a condition that touches nearly every aspect of a person’s life—physical comfort, emotional stability, and social well-being. Fortunately, it is also one of the greatest success stories in modern medicine: a disease once managed with invasive surgery is now curable with a short course of pills.

Still, the journey with ulcers requires more than just medication. It calls for awareness of symptoms, timely diagnosis, responsible lifestyle choices, and recognition of the emotional toll. For those living with the condition, healing means not only closing the ulcer but also regaining confidence in daily life—free from the fear of pain, bleeding, or recurrence.

Peptic ulcer disease teaches us something universal about health: the body’s defenses are strong but not infallible, and balance is everything. When that balance is restored—through science, medicine, and care—life can once again be lived with comfort, vitality, and peace.