We live in an age that worships busyness. Our devices beep with notifications, our schedules overflow, and our minds are pulled in countless directions every minute of the day. To keep up, many of us proudly claim to be multitaskers, juggling emails while chatting, switching between work and social media, or cooking dinner while watching a show. Multitasking seems like a superpower in a world demanding speed and efficiency.

But beneath the surface of this frenetic dance lies a more complicated truth about how our brains handle multiple tasks. While it may feel like we are accomplishing more, what is really happening inside our heads? Does multitasking enhance productivity, or does it silently erode the very cognitive functions we rely on?

To understand the profound effects of multitasking on the brain, we must embark on a journey through neuroscience, psychology, and the rhythms of daily life, examining both the allure and the hidden costs of dividing our attention.

The Neuroscience of Attention: A Delicate Balance

At its core, multitasking challenges one of the brain’s most precious resources: attention. Attention is not a limitless reservoir from which we can draw endlessly. Instead, it functions more like a spotlight, capable of focusing intensely on one thing or, at best, quickly shifting between a few things—but never truly spreading itself evenly across many tasks at once.

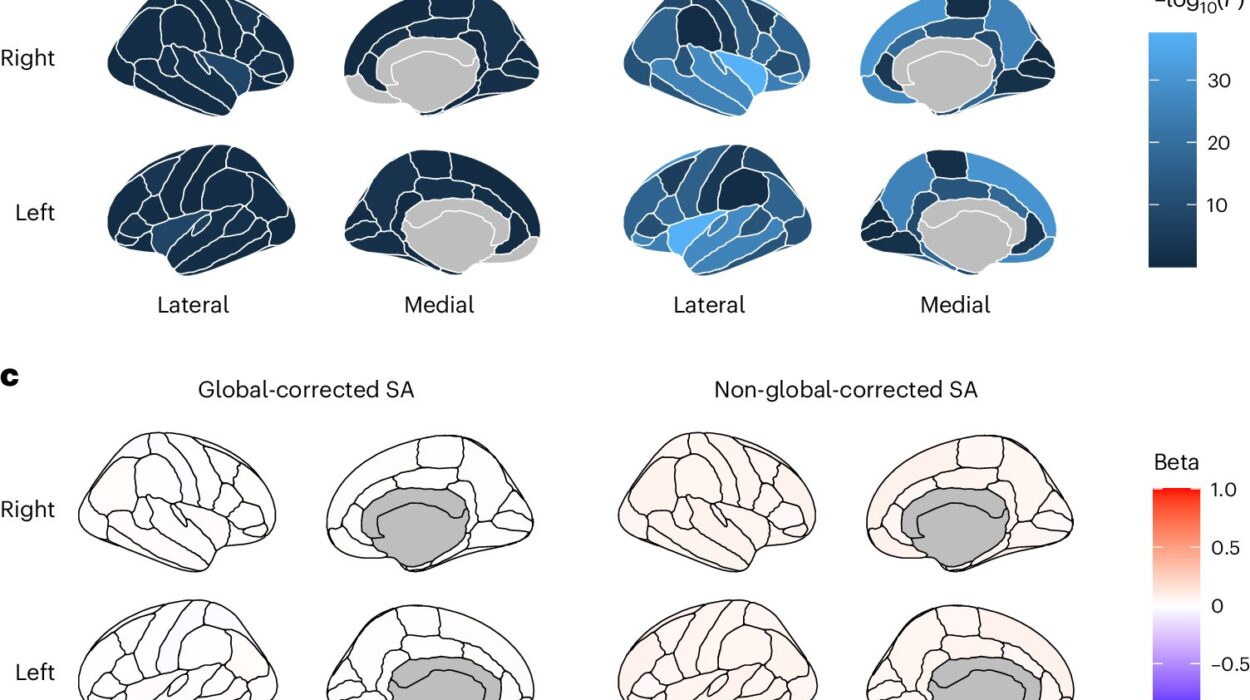

Neurologically, attention is governed by a complex network of regions, including the prefrontal cortex—the brain’s command center responsible for planning, decision-making, and problem-solving—and the parietal lobes, which help us orient ourselves in space and focus on relevant stimuli. The brain’s neurotransmitters, especially dopamine and norepinephrine, modulate attention, alertness, and executive control.

When we multitask, our brain rapidly toggles this spotlight back and forth between tasks, a process known as task-switching. This switching engages the frontoparietal network, which is highly active during tasks that require concentration and cognitive control. However, each switch demands time and energy. The brain must disengage from one task and reorient to another, and this “switch cost” results in decreased efficiency and increased error rates.

Myth of True Multitasking: Parallel Processing or Sequential Switching?

A common misconception is that the brain performs multiple tasks simultaneously by processing them in parallel. For simple, automatic actions—like walking and talking—this might be true because these activities rely on different neural circuits or have become so practiced they require little conscious attention.

However, when it comes to cognitively demanding tasks that require conscious thought, reasoning, or problem-solving, what we call multitasking is, in reality, rapid sequential switching. This means the brain momentarily focuses on one task, then shifts attention to another, then back again, and so forth.

This rapid toggling creates cognitive bottlenecks. For example, if you try to read an email while participating in a conference call, your brain may have trouble fully processing the information from either source. The result is shallow understanding, diminished retention, and an increased likelihood of making mistakes.

Studies using functional MRI have shown that when people switch tasks, brain regions involved in attention and cognitive control light up intensely, indicating high mental effort. The cost of this effort can lead to quicker mental fatigue compared to sustained focus on a single task.

Cognitive Load and Working Memory: The Hidden Toll

One of the key players affected by multitasking is working memory, the brain’s scratchpad where information is temporarily held and manipulated. Working memory allows us to keep track of ideas, numbers, instructions, or concepts while engaging in complex thinking.

When multitasking, working memory is bombarded with multiple streams of information. This overload decreases its capacity, leading to impaired reasoning and slower decision-making. Imagine trying to juggle multiple balls at once—adding more balls quickly overwhelms your ability to keep them all in the air. Similarly, excessive task-switching taxes working memory, causing mental clutter.

The prefrontal cortex, which governs working memory, also plays a role in inhibiting distractions and managing task priorities. Under multitasking conditions, its ability to filter irrelevant information is compromised, making the mind more prone to distraction. This can create a vicious cycle: distractions force more task switching, which increases cognitive load, which in turn reduces focus even further.

The Emotional and Psychological Impact of Multitasking

Multitasking doesn’t only affect raw cognition—it also influences emotional states and psychological wellbeing. The constant switching between tasks can increase stress hormones like cortisol, which negatively affect memory and mood.

People who frequently multitask tend to report higher levels of anxiety and find it harder to relax. The fragmented attention leaves the brain less capable of deep, reflective thought, often leading to feelings of overwhelm and burnout.

Moreover, multitasking can impact creativity. Creative insights often require the brain to enter a state of “diffuse mode,” where thoughts wander freely and connections form between disparate ideas. Fragmented attention makes entering this state more difficult, reducing innovation and problem-solving capacity.

Multitasking and Memory: The Cost of Shallow Encoding

Memory formation involves encoding experiences deeply enough to be stored for long-term recall. Multitasking disrupts this encoding process. When attention is divided, the brain cannot effectively process and consolidate new information.

Research shows that people who multitask while learning, such as checking their phones during lectures or meetings, retain less information. Their memories are often shallow and fragmented, making it difficult to retrieve useful knowledge later.

This phenomenon also explains why conversations conducted while multitasking often feel less satisfying. The brain fails to encode social cues and emotional subtleties fully, leading to misunderstandings and weaker interpersonal bonds.

Multitasking in the Age of Digital Distraction

The rise of digital technology has exacerbated multitasking habits. Smartphones, social media, and the internet flood the brain with constant stimuli and interruptions. Notifications and alerts act as potent distractions, hijacking attention and fragmenting mental focus.

Research highlights that the mere presence of a smartphone—whether in use or not—can reduce cognitive capacity. Studies have found that individuals perform worse on cognitive tasks if their phones are nearby, even if they don’t actively check them.

The addictive design of many apps, using variable rewards and social validation, encourages repeated task-switching. This creates a feedback loop where users compulsively check their devices, reducing sustained attention and impairing the ability to concentrate deeply.

The Social Cost: Multitasking and Human Connection

Beyond cognitive and emotional tolls, multitasking undermines the quality of human relationships. Engaging in conversations while distracted sends signals of disinterest and disrespect. The brain’s reduced capacity to process emotional nuances when attention is divided diminishes empathy.

In families, classrooms, and workplaces, multitasking can erode trust and connection. Children, for example, whose parents frequently multitask during interactions, may feel less emotionally secure and less able to regulate their own attention.

Work environments that glorify multitasking foster burnout and dissatisfaction. While workers may appear busy, their output and quality often suffer, and interpersonal collaboration weakens.

Can the Brain Improve Multitasking Abilities?

Despite its challenges, some individuals appear better at handling multiple tasks. This raises the question: can the brain improve its multitasking capacity?

Research suggests that extensive practice with specific tasks can create automaticity, reducing the cognitive load required. For instance, experienced drivers can talk or listen to music without impairing their ability to navigate traffic. However, this does not generalize to all types of multitasking—especially when tasks compete for the same cognitive resources.

Certain video games and cognitive training programs have been proposed to improve multitasking skills by enhancing working memory and attention control. While some evidence supports modest gains, the consensus remains that there are hard limits to human multitasking, especially for novel or complex tasks.

Strategies for Mitigating the Negative Effects of Multitasking

Understanding how multitasking impacts the brain empowers us to develop healthier habits. Mindfulness and meditation techniques can train the brain to sustain attention and reduce impulsive switching.

Setting clear priorities and batching similar tasks can help minimize switching costs. For example, checking and responding to emails during designated periods rather than continuously can preserve cognitive energy.

Turning off unnecessary notifications, using “do not disturb” modes, and creating distraction-free work environments support deeper focus. Breaks and rest are crucial, allowing the brain to recover and consolidate information.

The Paradox of Productivity: When Multitasking Backfires

The urge to multitask often stems from the desire to be more productive. Ironically, the evidence reveals the opposite: multitasking can drastically reduce efficiency. Tasks take longer, mistakes increase, and stress mounts.

The brain’s need for recovery between switches means that, even if multitasking feels urgent, focusing on one task at a time often leads to better results in less time. This insight challenges modern culture’s obsession with busyness, inviting us to rethink how we approach work and life.

Embracing Focus in a Fragmented World

Ultimately, the neuroscience of multitasking calls for a cultural shift toward valuing focus and presence. In a world that pulls us in many directions, reclaiming the ability to engage deeply with one task or one person can be revolutionary.

By understanding how our brains are wired, we can resist the illusion that doing many things at once is a strength. Instead, we can cultivate attention as a precious resource, protecting it fiercely amidst the noise.

The science is clear: multitasking is not a sign of cognitive superpower but a challenge to our brain’s natural architecture. Honoring our limits allows us to work smarter, think clearer, and connect more authentically—transforming not just productivity, but the very quality of our lives.