In a groundbreaking study led by researchers from the Complutense University of Madrid, scientists have discovered that when you eat might be just as important as what you eat—especially for people genetically predisposed to obesity. Published in the journal Obesity, the study reveals that eating earlier in the day can weaken the effects of genes that typically drive weight gain, providing new hope in the global fight against obesity.

This discovery isn’t just another piece in the ever-growing diet puzzle. It opens a new frontier in personalized nutrition, showing that meal timing could become a powerful tool in counteracting our inherited vulnerabilities.

What Time You Eat May Reshape Your Metabolism

For decades, scientists have understood that food, exercise, and sleep influence weight. But only recently has attention turned toward a subtler force: circadian rhythms—the body’s internal 24-hour clock that regulates everything from hormone levels to digestion. At the heart of this system lies the concept of a zeitgeber, a time cue that helps synchronize our internal clocks to the external world.

Light is the most powerful zeitgeber for the brain, but food acts as a time cue for peripheral clocks—those operating in metabolic tissues like the liver, pancreas, and fat stores. Eating at times misaligned with these biological rhythms can throw the whole system into chaos. Scientists have long suspected that this circadian misalignment might be a hidden driver of obesity, especially in people with high genetic risk.

Now, we have compelling evidence that meal timing can actually buffer the effects of those genetic risks.

The Study: A 12-Year Look at Genetics, Diet, and the Clock

The Spanish-led study analyzed data from 1,195 adults with overweight or obesity, mostly women, with an average age of 41. Participants were part of the ONTIME (Obesity, Nutrigenetics, Timing, and Mediterranean) study, which tracked them for over 12 years following a structured 16-week weight-loss program. The goal? To understand how long-term weight changes might be influenced not only by genes but by when participants ate their meals.

Using blood samples, researchers created a polygenic risk score for obesity. This score was calculated from nearly a million genetic variants—known as single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs—that are linked to increased body mass index (BMI). Then, they examined meal timing across weekdays and weekends to calculate the midpoint of food intake, or the average time between a person’s first and last meal of the day.

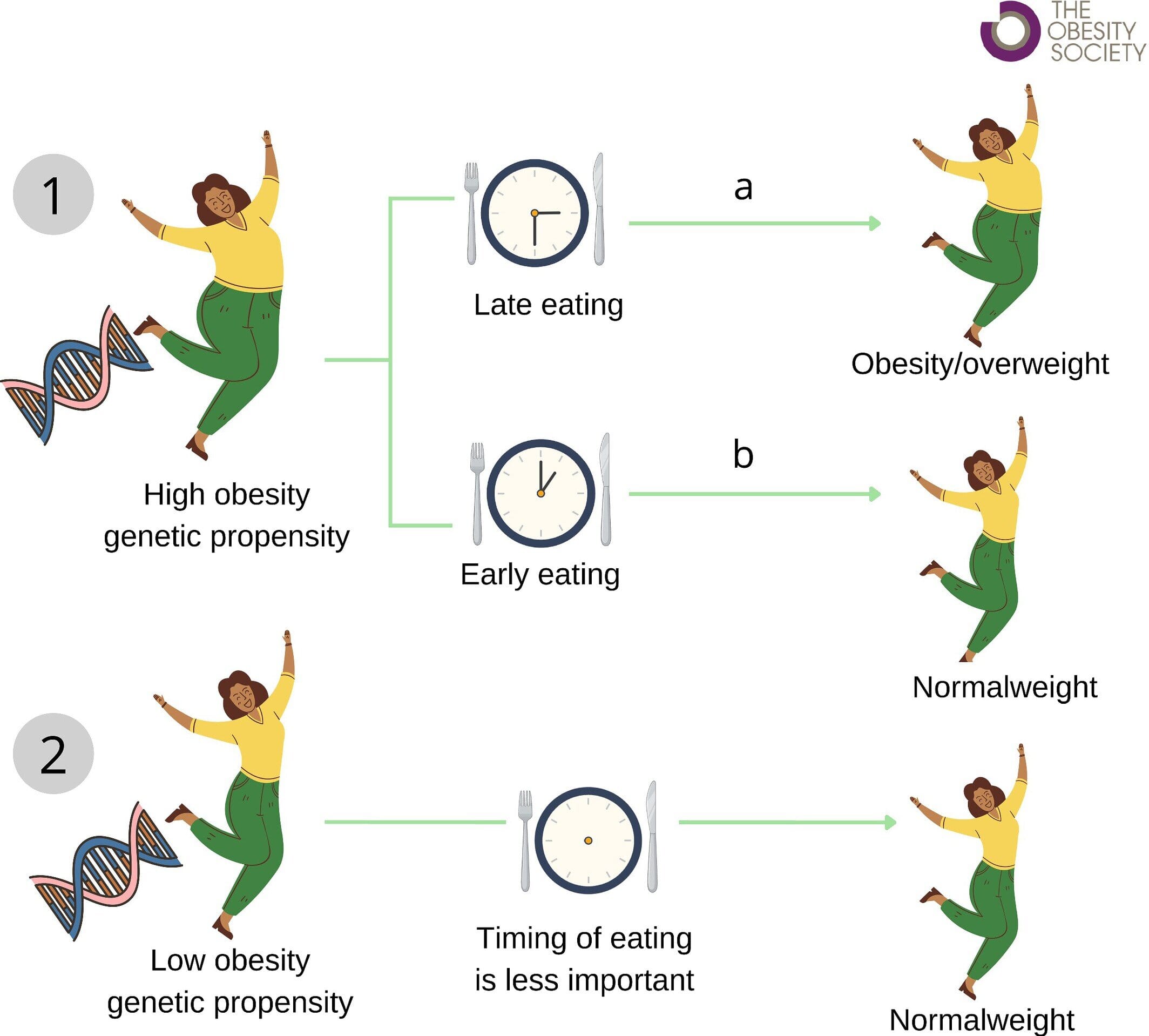

What they found was striking: each hour of delay in eating time was associated with a 0.952 kg/m² higher BMI at baseline and a 2.2% higher body weight 12 years later. But the effect was even more dramatic in people with a high polygenic risk score: in these individuals, every hour of delayed eating corresponded to a 2.21 kg/m² jump in BMI.

In simpler terms, eating late seems to “activate” obesity genes, while eating earlier can keep those genes quiet.

Why Is Eating Early So Protective?

To understand this, we need to look inside the body—into the mysterious world of circadian biology. Unlike what many assume, the brain’s master clock (located in the hypothalamus) is not the only clock in the body. Metabolic organs—like the pancreas, liver, and fat tissue—have their own clocks, which are strongly influenced by when we eat.

When we eat late in the day or at night, those peripheral clocks can fall out of sync with the brain’s central clock. This circadian misalignment can lead to reduced insulin sensitivity, slower calorie burn, increased fat storage, and disrupted hormone signals that regulate appetite and satiety.

The study’s findings suggest that for those genetically predisposed to obesity, such misalignment may magnify their risk. But aligning meals earlier in the day—when the body is naturally primed for digestion and metabolism—may restore harmony among the body’s clocks and help prevent excessive weight gain, even in those most vulnerable.

Personalized Diets: A New Era in Obesity Treatment

One of the most exciting implications of this research is its potential to revolutionize the way we approach obesity treatment. Rather than offering one-size-fits-all advice, doctors and nutritionists may soon tailor meal timing strategies to a person’s genetic profile.

If your genes put you at high risk for obesity, the solution may not be just calorie-cutting or more exercise—it may also involve moving your meals to earlier in the day. Breakfast could become your strongest ally.

As study co-author Dr. Marta Garaulet, a prominent chronobiologist, put it: “This research brings us closer to truly individualized nutrition plans—ones that take into account not only what we eat but also when we eat it, based on our genetic makeup.”

Rethinking Late-Night Culture in a 24/7 World

This study arrives at a critical cultural moment. Across the world—but especially in Western countries—eating schedules have shifted later and later. In Spain, where this study was conducted, dinner often begins after 9 p.m. In the United States, late-night snacking and 24-hour food delivery are part of modern life.

But our biology has not changed nearly as fast as our habits. The research suggests that our bodies may still be wired for a world where eating happened only during daylight hours.

It’s a wake-up call not only for individuals but also for public health policies. Encouraging earlier meal timing—through workplace lunch breaks, school cafeteria hours, or family dinner traditions—could make a major dent in global obesity rates.

What This Means for You

You don’t need to undergo genetic testing to benefit from this insight. For the average person, shifting meals to earlier in the day could improve weight control, energy levels, and metabolic health. Starting your day with a good breakfast and avoiding heavy dinners late at night could help synchronize your body’s internal clocks and promote long-term wellness.

If you’ve struggled with weight despite eating “right,” it might not be what you’re eating—it might be when you’re eating it.

This new understanding reminds us that the body is not a simple machine that runs on calories in and calories out. It’s a symphony of rhythms, genes, hormones, and habits. And when that music plays out of sync, health can suffer.

The Future of Chrononutrition

The field of chrononutrition—the science of how timing influences nutrition—is still young, but growing fast. Researchers are now exploring how eating windows, fasting periods, and nutrient timing interact with circadian biology and genetic traits.

The Complutense University of Madrid’s findings are among the first large-scale, long-term studies to demonstrate that meal timing can interact with genetic risk, offering a practical strategy for long-term weight maintenance.

Future clinical guidelines may include not just dietary recommendations, but daily schedules for eating that respect the body’s natural rhythms.

Final Thoughts: Time as Medicine

This new research doesn’t offer a miracle cure for obesity. But it offers something equally powerful: a new lens through which to understand our bodies. It shows that timing is not a footnote in the story of weight—it’s a main character.

By honoring our internal clocks, especially through meal timing, we may not only reduce our risk of obesity but also improve our relationship with food, sleep, and energy. And for those born with the genetic deck stacked against them, it’s a message of hope: genes are not destiny—especially if you eat on time.

More information: R De la Peña‐Armada et al, Early meal timing attenuates high polygenic risk of obesity, Obesity (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oby.24319

Divya Joshi et al, Timing Matters: Early Eating Mitigates Genetic Susceptibility for Obesity, Obesity (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oby.24350