Parkinson’s disease, a neurodegenerative disorder known for its characteristic tremors, rigidity, and slowed movement, has long puzzled researchers and patients alike. While the disease’s underlying causes remain elusive, a new study is shedding light on an intriguing possibility: that a little-known virus called human pegivirus (HPgV) might play a role in how Parkinson’s disease develops or progresses.

While the research doesn’t claim that HPgV causes Parkinson’s disease, it suggests that the virus, in combination with genetic factors, could influence immune function in the brain and contribute to disease progression. This discovery opens a new avenue for understanding Parkinson’s and potentially reshaping how we approach its treatment.

The Study That Sparked New Questions

The study, published in JCI Insight, focused on a largely unexplored aspect of Parkinson’s disease: the viruses that may be present in the brains of patients. Researchers, led by Barbara Hanson from Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, examined postmortem brain tissue from individuals with Parkinson’s and compared it to tissue from control subjects without the disease. What they found was striking.

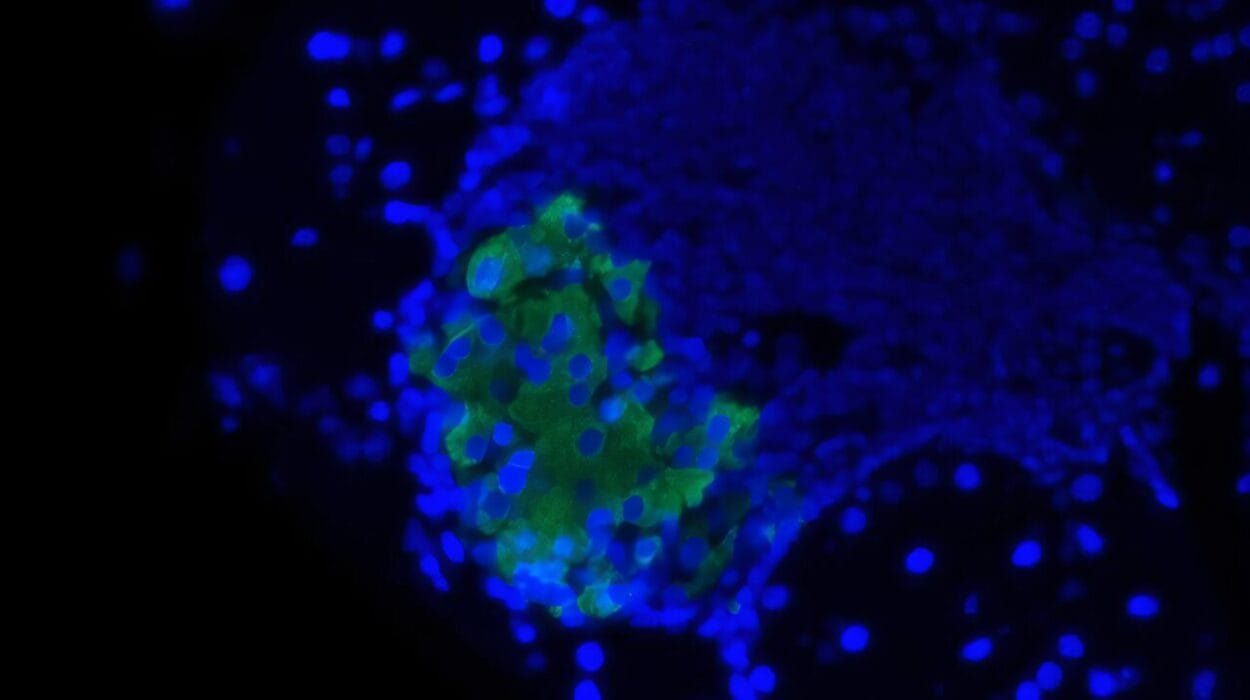

Human pegivirus (HPgV), a virus often regarded as harmless and rarely studied in detail, was found in the brains of some Parkinson’s patients but not in those without the disease. The virus was detected in four out of ten Parkinson’s patients’ brain tissues, but in none of the control samples. This discovery was further validated by genetic testing and imaging, suggesting that HPgV might have a significant role in the immune environment of Parkinson’s patients.

Not a Direct Cause, But a Potential Contributor

At this stage, researchers are clear that HPgV is not the direct cause of Parkinson’s disease. The findings do not suggest that the virus alone leads to the onset of the disease. Rather, HPgV appears to interact with genetic factors, particularly mutations in the LRRK2 gene, which is linked to hereditary forms of Parkinson’s. This interaction may contribute to how the disease develops or progresses, especially in genetically predisposed individuals.

What is clear, however, is that the presence of HPgV in the brain of some Parkinson’s patients could influence immune signaling pathways, which are critical to maintaining the health of neurons. This finding is groundbreaking because it hints at the possibility that viral infections, previously overlooked, could be an important environmental factor influencing the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

What is Human Pegivirus (HPgV)?

Human pegivirus is a virus that belongs to the flavivirus family, a group of viruses that also includes the hepatitis C virus. While HPgV has been identified in humans for several decades, it has often been dismissed as a harmless infection, with most people carrying the virus without ever showing symptoms. Its role in disease has been minimalized, but recent studies, including this one, are beginning to suggest that it may have more influence on our health than previously thought, especially in certain contexts like Parkinson’s disease.

HPgV is primarily found in blood and cerebrospinal fluid, but its presence in the brain was not well studied until this recent research. The study in JCI Insight is the first to suggest that HPgV could be linked to neurodegenerative diseases, particularly in individuals who have genetic mutations that make them more vulnerable to brain degeneration.

How HPgV Might Influence the Brain

The research team’s analysis showed that HPgV infection in the brains of Parkinson’s patients was associated with significant changes in immune signaling. In the infected brains, researchers observed an altered immune response, with some pathways suppressed or upregulated in ways that differed from uninfected patients. This may indicate that HPgV has a direct influence on the brain’s immune system, potentially contributing to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration.

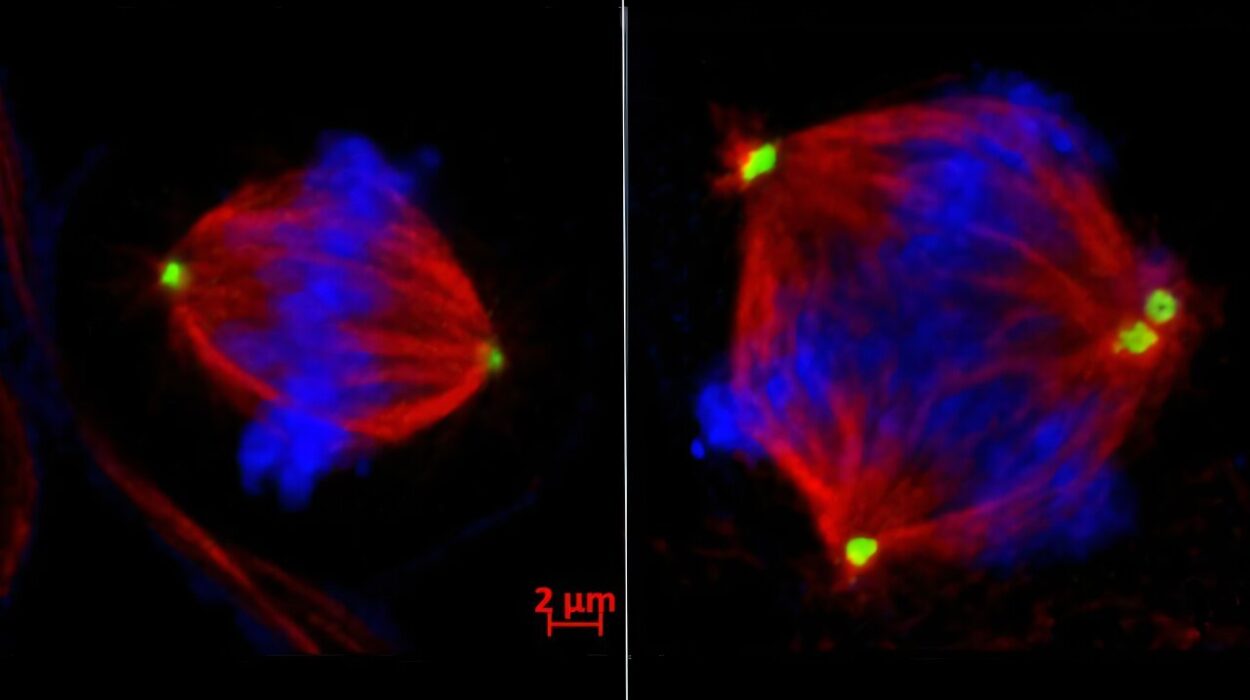

One of the most significant findings was that the virus appeared to influence the accumulation of tau tangles, a hallmark of neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. In the brains of HPgV-positive Parkinson’s patients, there was a noticeable increase in tau tangles in areas of the brain responsible for memory and emotion. This suggests that the virus may exacerbate the disease’s progression, particularly in areas associated with cognitive decline.

Furthermore, HPgV infection was found to alter synaptic function. The virus led to increased levels of complexin-2, a protein involved in neurotransmitter release, suggesting that the virus might interfere with normal communication between neurons. This disruption could contribute to the motor and cognitive symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

The Role of Genetics in the Virus’ Effect

The study also highlighted the critical role of genetics in determining how the body responds to HPgV infection. Specifically, the researchers found that the presence of the LRRK2 gene mutation—one of the most common genetic factors linked to Parkinson’s—shaped how immune cells in the brain reacted to the virus.

In individuals with the LRRK2 mutation, HPgV infection suppressed certain immune responses, specifically the IL-4 signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in controlling inflammation. In contrast, individuals without the LRRK2 mutation showed increased immune activity in response to the virus. This genetic difference suggests that a person’s genetic makeup could influence how they respond to viral infections and, in turn, how those infections may contribute to the onset or progression of Parkinson’s disease.

This finding is critical because it underscores the complex interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental factors like viral infections. It suggests that the effects of HPgV on the brain are not uniform but depend on an individual’s genetic background, which could influence their susceptibility to neurodegenerative diseases.

Implications for Parkinson’s Research

This study is a significant step forward in understanding the potential environmental triggers for Parkinson’s disease. For years, researchers have known that both genetics and environment contribute to the onset of the disease, but the exact mechanisms were unclear. With the discovery of HPgV’s possible role, researchers are now considering how other viruses might also interact with genetic factors to influence neurodegeneration.

The presence of HPgV in the brain may help to explain why some individuals with a genetic predisposition to Parkinson’s disease develop the condition, while others do not. It may also offer insight into how the immune system in the brain could become dysregulated, leading to inflammation and neuronal damage.

What’s Next for HPgV and Parkinson’s Disease Research?

While the findings from this study are promising, they are still in the early stages. The researchers caution that more studies are needed to fully understand the role of HPgV in Parkinson’s disease. Future research will focus on several critical questions:

- Does HPgV infection occur before or after the onset of Parkinson’s disease?

- How does the virus enter the brain, and which cells are affected?

- Can antiviral treatments help slow the progression of Parkinson’s disease in patients with HPgV?

Furthermore, researchers are exploring whether existing medications, such as those used to treat hepatitis C (a related flavivirus), might be effective in treating HPgV. While these drugs are not currently used for neurodegenerative diseases, their potential to target HPgV could open up new avenues for treatment.

Conclusion: A New Perspective on Parkinson’s Disease

The discovery that a virus like HPgV could play a role in Parkinson’s disease is a game-changer. It challenges the prevailing understanding of Parkinson’s as purely a result of genetic and environmental factors and introduces the possibility that viral infections could influence the disease’s course.

This study is a crucial step toward understanding how infections, immunity, and genetics intersect to shape neurodegenerative diseases. It reminds us that seemingly harmless viruses may have more profound effects on the brain than we realize, especially when they interact with genetic vulnerabilities.

While the connection between HPgV and Parkinson’s disease is not yet fully understood, it opens up exciting new possibilities for research and treatment. By examining how infections might influence brain health, we may one day uncover new strategies for preventing or treating Parkinson’s disease—strategies that incorporate not only genetic understanding but also the role of viral infections in shaping the immune environment of the brain.

As research continues, one thing is clear: the story of Parkinson’s disease is still being written, and the next chapter could bring surprising revelations that reshape our understanding of the disease and its treatment.