Cancer is often described as life’s most formidable adversary, and among its many forms, colorectal cancer stands as one of the most challenging. It quietly develops in the colon or rectum—parts of the digestive system that we rarely think about—until it becomes advanced enough to disrupt daily life. Because its earliest stages are often silent, people may not realize they carry this disease until it is already well established.

Yet, colorectal cancer is not merely a story of despair. It is also a story of survival, resilience, and progress. In recent decades, medicine has achieved remarkable advances in understanding what causes it, how to detect it early, and how to treat it effectively. Thousands of lives are saved each year thanks to better screening tools, greater awareness, and more personalized therapies.

To understand colorectal cancer is not only to grasp the science of tumors but also to explore how lifestyle, genetics, and medical innovation shape our destinies. It is about learning to recognize warning signs, to take preventive steps, and to support those living with the condition.

What Is Colorectal Cancer?

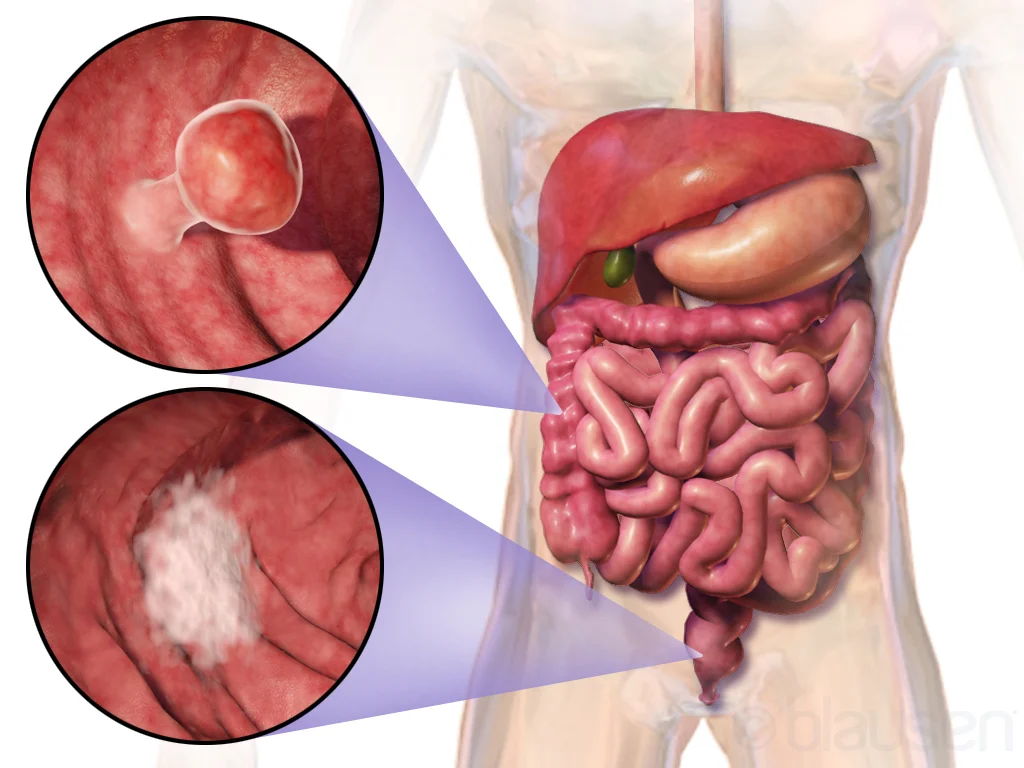

Colorectal cancer begins in the cells lining the colon (large intestine) or rectum, which together form the final section of the digestive tract. The colon absorbs water and nutrients from digested food, while the rectum stores stool before it leaves the body.

Most colorectal cancers develop from small growths called polyps, which arise from the inner lining of the colon or rectum. While most polyps are benign (non-cancerous), certain types—especially adenomatous polyps (adenomas)—can gradually transform into cancer over many years. This slow progression is why regular screening can prevent cancer: by removing polyps before they become malignant.

Once malignant cells form, they can grow uncontrollably, invade nearby tissues, and eventually spread (metastasize) to other organs such as the liver, lungs, or lymph nodes. This spread is often what makes colorectal cancer life-threatening.

The Global Burden of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Every year, more than 1.9 million people are diagnosed, and nearly 900,000 die from the disease. While once considered a cancer of older adults, its incidence is now rising in younger populations, a troubling trend that challenges assumptions and calls for urgent awareness.

The burden is not evenly distributed. High-income countries report higher rates, in part due to lifestyle factors such as diet, obesity, and sedentary behavior. However, as developing nations adopt similar lifestyles, colorectal cancer is becoming a global challenge. Survival rates vary dramatically depending on access to screening, quality of healthcare, and stage at diagnosis.

Causes of Colorectal Cancer

The causes of colorectal cancer are complex, involving a combination of genetic predisposition, environmental exposures, and lifestyle factors. Cancer begins when normal cells acquire mutations in their DNA that disrupt the normal cycle of growth and death. In colorectal cancer, several key pathways are involved, including mutations in genes like APC, KRAS, TP53, and mismatch repair genes.

Genetic Factors

A family history of colorectal cancer increases risk significantly. Inherited syndromes such as Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) account for a small but important fraction of cases.

- Lynch syndrome results from mutations in mismatch repair genes, leading to an accumulation of errors during DNA replication. People with Lynch syndrome often develop colorectal cancer before age 50 and may have multiple cancers throughout their lives.

- FAP is caused by mutations in the APC gene, leading to the development of hundreds or thousands of polyps in the colon and rectum. Without surgical intervention, cancer is virtually inevitable.

Other genetic factors may not guarantee cancer but increase susceptibility when combined with environmental triggers.

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

Our daily choices play a powerful role in colorectal cancer risk. Diets high in red and processed meats, low in fiber, and rich in refined sugars are strongly linked to increased risk. Conversely, diets abundant in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains appear protective.

Physical inactivity, obesity, and excessive alcohol use are additional contributors. Smoking, long associated with lung cancer, also increases the risk of colorectal cancer.

Chronic inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease raise risk by creating an environment of ongoing irritation and DNA damage in the colon lining.

The Microbiome Connection

In recent years, research has illuminated the role of the gut microbiome—the trillions of microorganisms living in the intestines—in colorectal cancer. Certain bacterial imbalances can promote inflammation, produce carcinogenic compounds, or interfere with immune surveillance. While this area of research is still evolving, it suggests that nurturing a healthy microbiome may be part of future preventive strategies.

Symptoms of Colorectal Cancer

One of the most dangerous aspects of colorectal cancer is that early stages often produce no symptoms. By the time signs appear, the cancer may already be advanced. Still, recognizing symptoms early can save lives.

Common symptoms include:

- Persistent changes in bowel habits, such as diarrhea, constipation, or narrowing of stool.

- Blood in the stool, which may appear bright red or dark and tarry.

- Abdominal pain, cramping, bloating, or discomfort.

- A feeling of incomplete bowel emptying.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Fatigue and weakness, often due to hidden blood loss leading to anemia.

It is important to note that these symptoms can also be caused by benign conditions like hemorrhoids or infections. However, when persistent, they should never be ignored.

Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer

Detecting colorectal cancer early dramatically improves survival. Diagnosis involves a combination of medical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, imaging, and endoscopic procedures.

Screening

Screening is the most effective weapon against colorectal cancer. It detects cancer at earlier, more treatable stages and can even prevent cancer by removing polyps before they turn malignant.

The most common screening tool is colonoscopy, in which a flexible tube with a camera is inserted into the rectum to examine the entire colon. Colonoscopy allows for both detection and removal of suspicious polyps.

Other screening options include:

- Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT): These detect hidden blood in stool, which may indicate cancer or polyps.

- Stool DNA test: Detects DNA mutations shed by tumors into the stool.

- Flexible sigmoidoscopy: Examines only the lower part of the colon.

- CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy): Uses imaging to visualize the colon.

Screening typically begins at age 45 for average-risk individuals, though those with family history or genetic syndromes may need to start earlier.

Diagnostic Procedures

If screening or symptoms suggest cancer, further diagnostic procedures are performed:

- Biopsy: Tissue samples taken during colonoscopy are examined under a microscope to confirm malignancy.

- Imaging tests: CT scans, MRI, PET scans, and ultrasound help determine the cancer’s extent and whether it has spread.

- Blood tests: While not diagnostic, markers like carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may help monitor treatment response.

Staging of Colorectal Cancer

Staging describes how far cancer has spread, guiding treatment decisions. The TNM system is commonly used:

- T (Tumor): Size and extent of the primary tumor.

- N (Nodes): Spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- M (Metastasis): Spread to distant organs.

Stages range from I (localized) to IV (advanced, with distant metastases). Prognosis worsens with advancing stage, underscoring the importance of early detection.

Treatment of Colorectal Cancer

Treatment is tailored to the stage of cancer, the patient’s overall health, and individual preferences. It often involves a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy.

Surgery

Surgery is the cornerstone of treatment for localized colorectal cancer.

- Polypectomy and local excision: For very early cancers confined to polyps, removal during colonoscopy may be sufficient.

- Colectomy (colon resection): Removal of the cancerous section of colon, often with rejoining of the remaining parts.

- Proctectomy: Removal of part or all of the rectum for rectal cancers.

In advanced cases, surgery may involve removal of nearby lymph nodes or creation of a colostomy, where stool exits the body into a bag attached to the abdomen.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells or stop them from dividing. It is often used after surgery (adjuvant therapy) to kill remaining cancer cells or before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy) to shrink tumors.

Common drugs include 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), capecitabine, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan. These may be combined in regimens such as FOLFOX or FOLFIRI.

Side effects—nausea, fatigue, hair loss, and risk of infection—can be challenging, but supportive care has improved quality of life during treatment.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation is particularly important for rectal cancer, where it can shrink tumors before surgery or destroy residual cells after surgery. Modern techniques, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), allow precise targeting while sparing healthy tissue.

Targeted Therapy

Unlike chemotherapy, which attacks all rapidly dividing cells, targeted therapy interferes with specific molecules driving cancer growth. For example:

- Bevacizumab targets VEGF, blocking blood supply to tumors.

- Cetuximab and panitumumab target EGFR, effective in cancers without KRAS mutations.

These drugs are often used in advanced cases, extending survival and sometimes reducing tumor size dramatically.

Immunotherapy

The immune system has immense power to fight cancer, and immunotherapy harnesses this potential. Drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, release the brakes on immune cells, allowing them to attack tumors.

Immunotherapy has shown remarkable success in patients with mismatch repair–deficient or microsatellite instability–high colorectal cancers, a subset previously resistant to standard treatments.

Living with Colorectal Cancer

Beyond medical treatment, colorectal cancer profoundly affects emotional and social well-being. Fear, uncertainty, and the physical impact of treatment can weigh heavily on patients and families.

Support groups, counseling, and palliative care play vital roles in improving quality of life. Nutritionists help patients adapt diets to maintain strength, while physical therapists assist with recovery after surgery. Emotional resilience, community support, and compassionate care are as important as chemotherapy or surgery.

Prevention: The Power of Awareness and Action

Colorectal cancer is one of the most preventable cancers. Regular screening remains the strongest defense, but lifestyle choices matter enormously.

Eating a fiber-rich diet, maintaining a healthy weight, staying physically active, avoiding tobacco, and limiting alcohol all reduce risk. Aspirin, under medical supervision, has also been shown to lower risk in some individuals.

Importantly, prevention is not only an individual responsibility but a societal one. Public health campaigns, affordable access to screening, and policies that promote healthy environments are crucial to reducing the global burden.

The Future of Colorectal Cancer Care

Science is rapidly advancing the fight against colorectal cancer. Liquid biopsies—simple blood tests detecting tumor DNA—promise earlier and less invasive detection. Artificial intelligence is being used to enhance colonoscopy by spotting polyps that human eyes might miss. Personalized medicine, guided by genetic profiling of tumors, allows treatments to be matched precisely to an individual’s cancer.

The vision of the future is clear: to detect colorectal cancer earlier, to treat it more effectively, and to help people not merely survive but thrive after diagnosis.

Conclusion: A Call to Vigilance and Hope

Colorectal cancer is a formidable disease, but it is not unbeatable. Knowledge is our most powerful ally—knowing the risk factors, recognizing symptoms, undergoing screening, and supporting scientific progress.

For those who face it, colorectal cancer is a journey through uncertainty and struggle, but also through courage, love, and resilience. For society, it is a reminder that health is not to be taken for granted but safeguarded with vigilance. And for medicine, it is a field of ever-expanding discovery, where science and humanity meet in the service of life.