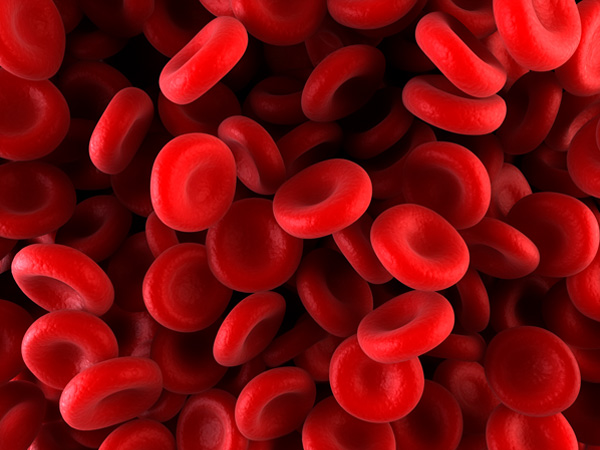

Imagine a small cut on your finger. For most people, within minutes, the bleeding slows, a scab begins to form, and the wound quietly heals. But for someone with hemophilia, that same minor cut—or worse, an internal injury invisible to the eye—can lead to prolonged bleeding, pain, and sometimes life-threatening complications. Hemophilia is not just a medical condition; it is a reminder of how delicate the human body truly is, and how much we rely on the intricate system of clotting to keep us alive.

Blood clotting is a marvel of biology: a symphony of proteins, cells, and chemical signals working together to seal wounds and restore balance. In people with hemophilia, a crucial piece of this orchestra is missing, disrupting the entire harmony. The result is a condition that has challenged humanity for centuries, one that has been misunderstood, feared, and even called “the royal disease” because of its prevalence in European monarchies. Today, thanks to scientific discovery and medical innovation, we understand hemophilia with greater clarity than ever before. Yet, for those living with it, the journey of managing this condition is deeply personal and lifelong.

This article explores hemophilia in depth—its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment—while also shedding light on the emotional, social, and scientific dimensions of living with a disorder that makes every bruise or bleed more than just a passing concern.

What is Hemophilia?

Hemophilia is a rare genetic bleeding disorder in which the blood does not clot properly. This happens because the body lacks sufficient levels of clotting factors—specialized proteins that work in a chain reaction to form stable clots when blood vessels are injured. Without these proteins, bleeding lasts longer than normal, and sometimes occurs spontaneously inside the body, especially in joints and muscles.

There are two primary types:

- Hemophilia A, caused by a deficiency of clotting factor VIII (8).

- Hemophilia B, caused by a deficiency of clotting factor IX (9).

Both types present similar symptoms but differ in their genetic causes and specific treatments. A third, much rarer form, hemophilia C, results from a deficiency in factor XI (11) and usually causes milder symptoms.

The severity of hemophilia depends on how much clotting factor is missing. People with mild hemophilia may only bleed excessively during surgery or major trauma, while those with severe hemophilia can experience spontaneous internal bleeding, even without injury.

The Genetic Cause of Hemophilia

At its core, hemophilia is a genetic condition passed down through families. The genes responsible for clotting factors VIII and IX are located on the X chromosome. This is why hemophilia is described as an X-linked recessive disorder.

Males, who have one X and one Y chromosome, are much more likely to develop hemophilia. If their single X chromosome carries the defective gene, they will have the disease because they lack a backup copy. Females, who have two X chromosomes, are less likely to have hemophilia because if one X carries the faulty gene, the other usually compensates. However, women can be carriers, meaning they can pass the defective gene to their children.

- If a mother is a carrier and has a son, there is a 50% chance he will have hemophilia.

- If she has a daughter, there is a 50% chance the daughter will be a carrier.

In rare cases, women can have hemophilia if both of their X chromosomes carry the mutation, or if their one healthy X chromosome is inactivated in a process known as “skewed X-inactivation.”

While most cases are inherited, about one-third of all hemophilia cases occur due to a spontaneous genetic mutation—a random change in DNA that was not present in previous generations.

How Hemophilia Affects the Body

To understand hemophilia, it helps to know how clotting normally works. When a blood vessel is injured:

- Platelets rush to the site, clumping together to form a temporary plug.

- Clotting factors activate one another in a complex chain reaction, creating fibrin strands that weave through the platelet plug and strengthen it into a stable clot.

- The bleeding stops, and healing begins.

In hemophilia, one of the critical steps in this cascade is missing. Without factor VIII or IX, the clotting process is incomplete, leaving the wound vulnerable to prolonged or uncontrolled bleeding. This doesn’t just happen on the skin’s surface. Internal bleeding is common, especially in joints like knees, elbows, and ankles. Over time, repeated bleeds into joints cause swelling, pain, and eventually permanent damage known as hemophilic arthropathy.

Symptoms of Hemophilia

Hemophilia symptoms vary by severity but often appear in early childhood. Some infants are diagnosed after unusual bleeding during circumcision or following immunization shots. For others, the first sign might be excessive bruising or unexplained bleeding after a minor fall.

Common Symptoms

- Prolonged bleeding from cuts or injuries

- Large, deep bruises

- Frequent nosebleeds that are hard to stop

- Bleeding into joints, causing swelling, warmth, stiffness, and pain

- Unusual bleeding after surgery, dental work, or even tooth loss

Severe Symptoms

- Spontaneous internal bleeding, especially in joints and muscles

- Blood in urine or stool (indicating internal bleeding in kidneys or intestines)

- Bleeding in the brain, which may cause headaches, vomiting, seizures, or paralysis—a medical emergency

Children with severe hemophilia may experience “target joints,” where repeated bleeding occurs in the same joint, leading to progressive damage. Over years, untreated joint bleeds cause chronic pain, deformities, and mobility limitations.

The Emotional and Social Impact

Beyond the physical symptoms, hemophilia carries emotional and social challenges. Parents of children with hemophilia often live with constant vigilance, monitoring every play activity or bump for signs of internal bleeding. Children may feel isolated when restricted from contact sports or rough play, while teenagers and adults may struggle with independence when their health requires frequent treatments.

Living with hemophilia can also bring financial and logistical burdens. Treatments are expensive, requiring lifelong medical care. In countries with limited healthcare resources, people with hemophilia may face shortened life expectancy, disability, or death from uncontrolled bleeding.

Yet, many people with hemophilia also demonstrate remarkable resilience. With education, support, and access to treatment, they can lead full and active lives, pursuing careers, sports, and family life.

Diagnosis of Hemophilia

Diagnosing hemophilia involves a combination of medical history, family history, physical examination, and laboratory testing.

- Blood tests can measure how long it takes for blood to clot and whether clotting factors are missing or deficient.

- Factor assays specifically determine which clotting factor is deficient and at what level.

- Genetic testing can confirm the exact mutation responsible and identify carriers within families.

Early diagnosis is critical. For families with a known history, hemophilia can be detected through prenatal testing or immediately after birth. This allows doctors to intervene early, prevent complications, and provide proper counseling for parents.

Treatment of Hemophilia

The cornerstone of hemophilia treatment is replacement therapy—infusing the missing clotting factor into the bloodstream so that normal clotting can occur. These treatments can be life-saving, especially in severe cases.

Factor Replacement Therapy

- Factor VIII concentrates for hemophilia A

- Factor IX concentrates for hemophilia B

These concentrates may be derived from donated human plasma (plasma-derived) or created synthetically in a laboratory (recombinant). Recombinant factors are generally preferred due to lower risks of infection.

Factor replacement can be given:

- On demand: to stop bleeding when it occurs

- Prophylactically: as regular infusions to prevent bleeding episodes, especially in children with severe hemophilia

Emerging Therapies

Medical science is making strides beyond traditional replacement therapy:

- Gene therapy: introducing functional copies of the defective gene to restore clotting factor production. Early trials show promise of long-term correction.

- Non-factor therapies: drugs like emicizumab, a monoclonal antibody for hemophilia A, mimic the function of factor VIII and reduce bleeding without regular infusions.

- Extended half-life factors: newer formulations last longer in the bloodstream, reducing the frequency of treatments.

Managing Bleeding Episodes

Alongside factor replacement, supportive care may include:

- Pain management for joint bleeds

- Physical therapy to restore mobility

- Surgery in cases of severe joint damage

Complications of Hemophilia

Even with treatment, complications can arise:

- Inhibitors: Some patients develop antibodies against infused clotting factors, making treatment less effective. Managing inhibitors requires specialized therapies and is one of the greatest challenges in hemophilia care.

- Joint damage: Repeated bleeds without proper management can lead to arthritis and disability.

- Infections: In the past, contaminated plasma-derived products transmitted viruses like HIV and hepatitis C. Modern safety measures have largely eliminated this risk, but the historical legacy remains painful for many.

Living with Hemophilia

Living with hemophilia requires adaptation, but it does not mean giving up on life’s possibilities. With proper treatment and awareness, people with hemophilia can live nearly normal life spans.

Children are encouraged to stay active, though contact sports may be limited. Swimming, walking, and cycling are excellent choices to maintain fitness and joint health. Education about self-infusion allows many to manage treatment independently, empowering them to travel, work, and build families.

Support networks—both local and international—play a critical role. Organizations like the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) provide education, advocacy, and resources to ensure people worldwide have access to care.

The Future of Hemophilia Care

The story of hemophilia has transformed dramatically over the last century. Once considered a devastating and often fatal condition, it is now manageable with modern science. The future holds even greater hope:

- Gene therapy may one day provide a permanent cure, freeing patients from lifelong infusions.

- Global initiatives aim to bring equal access to treatment in all parts of the world, closing the gap between developed and developing countries.

- Personalized medicine will refine treatments, tailoring them to each individual’s genetic profile and specific needs.

As medicine advances, hemophilia is no longer solely a story of limitation but increasingly one of resilience, possibility, and hope.

Conclusion: Beyond Blood

Hemophilia is more than a bleeding disorder—it is a testament to the delicate balance of life. It reveals how a single missing protein can reshape a person’s destiny, but it also demonstrates the power of science, compassion, and human determination.

For those living with hemophilia, every bruise or joint pain carries meaning. For their families, every step forward is a victory. And for the medical community, every breakthrough is a promise that the future will be brighter than the past.

To understand hemophilia is to understand both the fragility and the resilience of the human condition. It is to see that health is not just about what is missing, but about what we can create—together—to restore balance, heal, and thrive.