For generations, scientists have known that Earth’s core is dominated by iron. It is a realm of staggering pressure and unimaginable heat, buried thousands of kilometers beneath our feet. Yet even with all that iron, something has never quite added up. The core’s density is just a little too low for it to be made of pure iron alone. That small mismatch has whispered a quiet secret for decades: something lighter must be hiding there.

Now, a new study published in Nature Communications suggests that the missing ingredient may be astonishing in scale. The researchers propose that Earth’s core could hold the equivalent of 9 to 45 oceans’ worth of hydrogen. If true, this hidden reservoir does more than reshape our picture of the deep Earth. It challenges a long-standing story about how our planet got its water in the first place.

Chasing Hydrogen into the Deepest Darkness

Understanding the composition of Earth’s core is one of science’s most daunting challenges. It lies far beyond direct reach, crushed by extreme pressures and heated to extraordinary temperatures. No drill can descend that far. No direct sample can be retrieved.

Hydrogen, the lightest and smallest element, is especially elusive. Many traditional techniques struggle to detect it clearly. Earlier attempts to estimate hydrogen content relied on indirect clues, such as observing how iron’s crystal lattice expands when hydrogen slips inside it to form iron hydrides. These indirect methods produced wildly uncertain estimates, spanning four orders of magnitude. The uncertainty was enormous.

The new research team decided to approach the problem differently. Instead of inferring hydrogen’s presence from subtle distortions, they recreated the core’s extreme environment in the laboratory itself.

Rebuilding the Core in the Palm of a Hand

To mimic the deep interior of Earth, the scientists used laser-heated diamond anvil cells. These remarkable devices can squeeze materials between two diamonds while blasting them with lasers, reaching pressures of up to 111 gigapascals and temperatures around 5100 Kelvin. These conditions approach those found deep within our planet.

Inside these tiny chambers, the team placed samples of core-like iron alongside hydrous silicate glass, which represented Earth’s early magma oceans. As the materials were compressed and heated, they melted—echoing the violent conditions of the young Earth as its interior separated into layers.

This was more than a dramatic recreation. It was a controlled attempt to watch how hydrogen behaves when iron and molten silicates interact under extreme conditions.

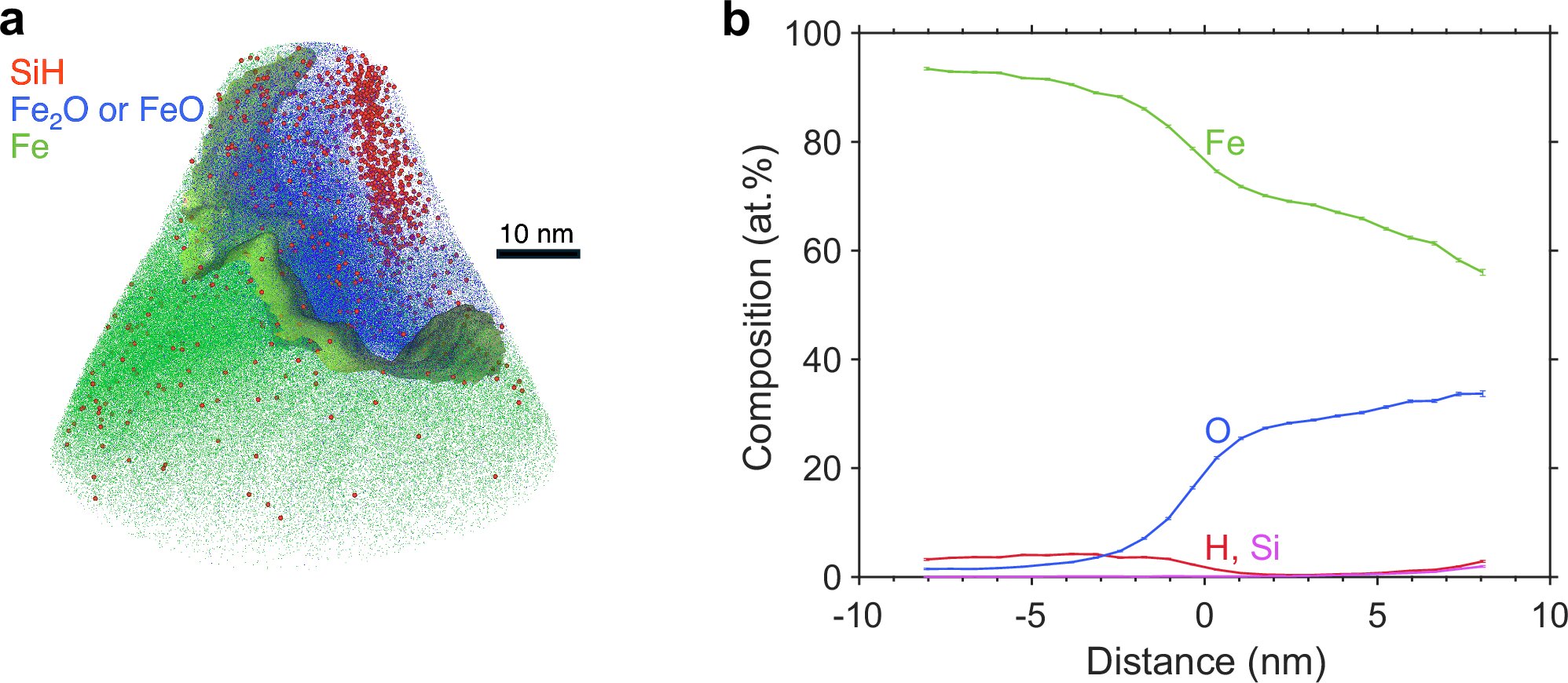

Once the samples were quenched—rapidly cooled to freeze their structure—the team turned to a powerful imaging technique called atom probe tomography (APT). This method allowed them to build a three-dimensional compositional map at nanoscale resolution, effectively reconstructing the atomic arrangement of the material.

What they found was striking.

A 1:1 Clue Hidden in Nanostructures

The APT analysis revealed Si-O-H-rich nanostructures formed during the experiments. Within these tiny structures, the researchers measured the ratio of silicon to hydrogen, discovering it was close to 1:1 in molar terms.

That simple ratio carried enormous weight. The amount of silicon in Earth’s core is relatively well constrained compared to hydrogen. By tying hydrogen content to silicon in a measurable proportion, the team could estimate how much hydrogen might realistically reside in the core.

Their calculations suggest that Earth’s core contains approximately 0.07 to 0.36 weight percent hydrogen. Translated into something more intuitive, that equals the mass of 9 to 45 oceans of water.

This hydrogen is not sloshing around as liquid water in the core. It exists in elemental form, dissolved within iron and bound in high-pressure structures. But its quantity, if accurate, is immense.

And that is where the story takes a dramatic turn.

Rethinking the Origin of Earth’s Water

For many years, a popular idea has held that much of Earth’s water arrived later in its history, delivered by icy comets striking the young planet. In this scenario, water was an external gift, arriving after Earth had largely formed.

But the presence of a large hydrogen reservoir in the core complicates that narrative.

According to the researchers, if cometary delivery were responsible for most of Earth’s hydrogen, then hydrogen would be expected to remain largely in the planet’s shallower layers. Instead, the evidence points to significant hydrogen trapped deep within the core itself.

This suggests that hydrogen—and by extension, much of Earth’s water—was incorporated earlier, during the planet’s accretion phase, when it was still forming and differentiating into core and mantle.

The team proposes that hydrogen may have been acquired “in situ,” interacting with oxygen during Earth’s formation. They note that this scenario is dynamically plausible and compatible with a hydrogen ingassing model, in which a primordial atmosphere interacted with a global magma ocean.

They also point out that Earth may have been built largely from enstatite chondrite-like materials, which have isotopic similarities to our planet and contain enough hydrogen to account for more than three oceans of water, along with Earth-like hydrogen isotopic signatures.

In this view, water is not a late delivery from distant comets. It is woven into Earth’s very formation story.

A Study with Caution and Care

Despite the bold implications, the researchers are careful not to overstate their conclusions. They acknowledge several limitations.

One concern is the possibility of residual hydrogen in the APT chamber, which could have artificially inflated measured hydrogen levels. There are also uncertainties in the exact silicon content of the core, which directly affects hydrogen estimates. The assumption that sufficient hydrogen was present during Earth’s accretion remains open to debate. Additionally, fracturing of the samples during analysis may have introduced errors in data collection.

These caveats matter. They remind us that science moves forward not through dramatic proclamations, but through careful testing, revision, and refinement.

Still, even with these uncertainties, the study offers one of the most direct experimental constraints yet on hydrogen in Earth’s core.

Why This Hidden Ocean of Hydrogen Matters

At first glance, hydrogen buried deep in the core may seem remote from daily life. But its implications reach to the heart of one of humanity’s most profound questions: How did Earth become a world of oceans?

If hydrogen was incorporated early, during the planet’s formation, then Earth’s water may not be a fortunate late arrival. It may be a fundamental outcome of how our planet assembled. The oceans, rivers, clouds, and rain that define our world could trace their origins back to processes unfolding in a molten, chaotic young Earth.

The idea that up to 45 oceans’ worth of hydrogen lie hidden within the core also reshapes how scientists model the planet’s internal structure and evolution. The presence of light elements affects density, thermal history, and the dynamics of core formation. Understanding exactly how much hydrogen is present refines our picture of Earth from the inside out.

Perhaps most importantly, this research narrows the uncertainty that has long surrounded hydrogen estimates. Instead of guesses spanning four orders of magnitude, scientists now have experimental data tying hydrogen content to measurable silicon ratios under core-like conditions.

The core remains unreachable, locked in darkness beneath thousands of kilometers of rock. Yet through diamond anvils, laser heat, and atomic-scale imaging, scientists have drawn back the curtain just a little further.

Deep beneath us, within the iron heart of our planet, there may be a hidden ocean—not of water as we know it, but of hydrogen that helped make water possible. And in that revelation, the story of Earth’s beginnings becomes both clearer and more extraordinary.

Study Details

Dongyang Huang et al, Experimental quantification of hydrogen content in the Earth’s core, Nature Communications (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-026-68821-6