In hospital nurseries, the smallest patients fight the biggest battles. Premature lungs struggle to breathe. Fragile hearts learn to beat outside the womb. And sometimes, something far more unexpected slips quietly into the story.

At Penn State College of Medicine, physicians recently described two devastating cases of infant meningitis caused by a bacterium most doctors once thought of as little more than a soil dweller. The organism belongs to the genus Paenibacillus, a group of microbes commonly found in the soil microbiome and historically regarded as an uncommon human pathogen.

But in these infants, it was anything but harmless.

Reports from Uganda had already linked Paenibacillus to destructive neonatal infections, including abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid, seizures, and extensive brain injury. Now, similar cases are emerging in multiple U.S. states. And with them comes a troubling realization: the antibiotics routinely used for infant bacteremia and meningitis may not be enough when this bacterium is involved.

What once seemed rare may, in fact, be underrecognized.

A Premature Beginning and a Sudden Storm

The first child was born at just 26 weeks’ gestation, a tiny fighter from the start. At two months old, she developed respiratory distress and seizures. Doctors quickly drew blood cultures. Under the microscope, they saw gram-negative rods. Blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures grew what appeared to be Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus.

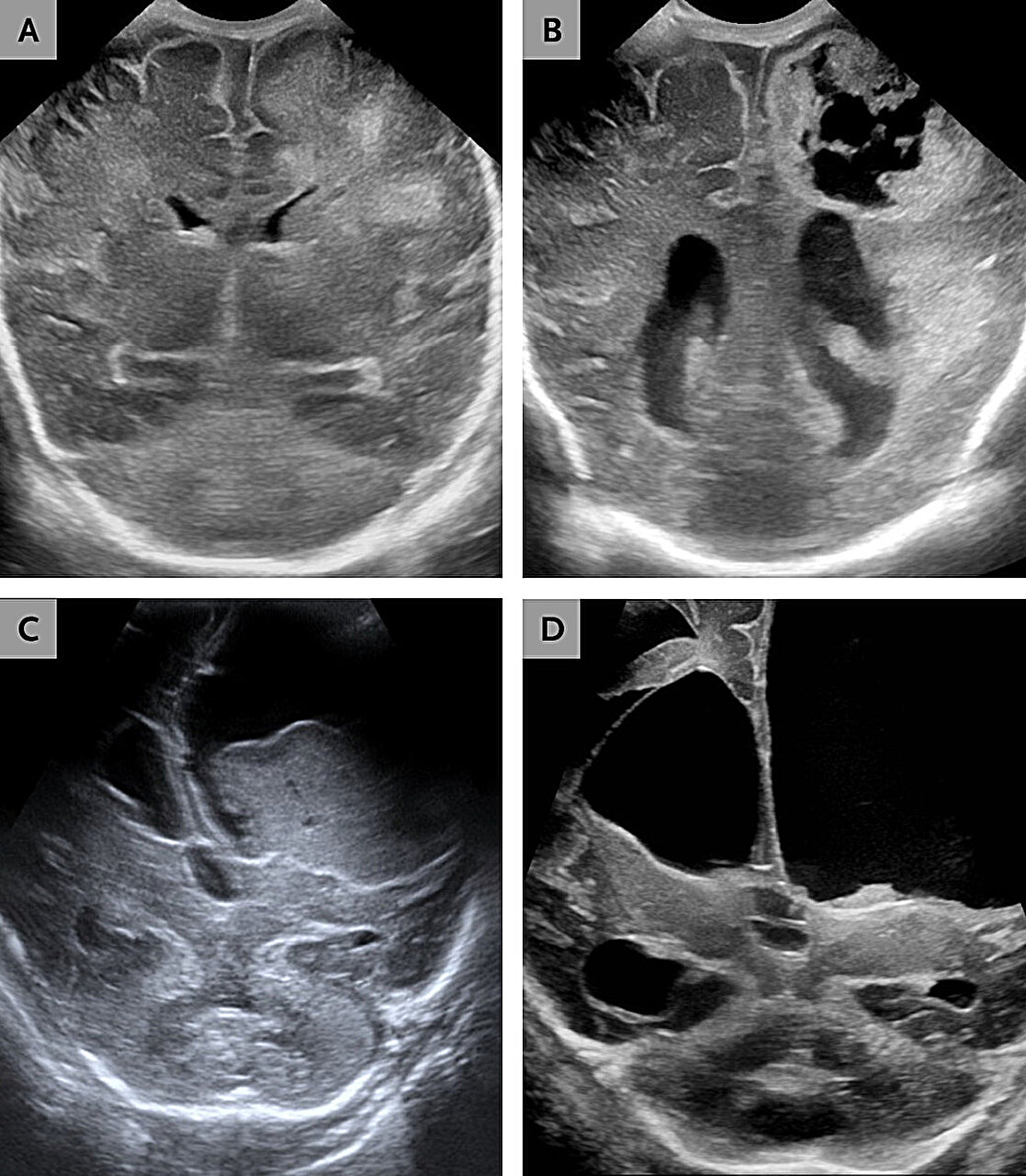

Brain imaging soon revealed the true scale of the damage. There was progressive hydrocephalus, a dangerous buildup of cerebrospinal fluid. There was encephalomalacia, softening and destruction of brain tissue. There were abscesses forming within the brain itself. Surgeons had to place a ventriculoperitoneal shunt to drain excess fluid and relieve pressure.

Treatment was aggressive. The infant received continuous-infusion meropenem for eight weeks. Midway through therapy, doctors added vancomycin and rifampin because her cerebrospinal fluid remained abnormal. Something wasn’t responding as expected.

Four days after symptoms began, doctors started thiamine supplementation. The reason was chilling. These bacteria produce an enzyme that destroys thiamine, a vitamin essential for brain function. Without it, brain tissue can suffer further injury.

At eight months of age, the child survived—but not unscarred. She could maintain eye contact and smile. Yet she could not feed orally, sit unsupported, or roll independently. The infection had permanently altered the course of her life.

When the Brain Begins to Dissolve

The second case, previously reported in Minnesota, involved another preterm infant, born at 33 weeks’ gestation. At just 37 days old, the baby was brought to the hospital for poor feeding and unresponsiveness.

Again, blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures were identified as P. thiaminolyticus. Brain imaging revealed something even more harrowing: liquefactive meningoencephalitis. In this process, brain tissue begins to dissolve into a viscous liquid.

The infant was treated with intravenous ampicillin and required placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. But clinical deterioration continued. Feeding difficulties worsened. Seizures followed. At eleven months of age, the child died.

Two infants. Two premature beginnings. Two infections that tore through developing brains with terrifying efficiency.

A Case of Mistaken Identity

At first, both infections appeared to be caused by Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus. That identification came from initial laboratory testing. But something did not quite add up.

Researchers performed whole-genome sequencing on bacterial isolates from both infants. The results changed the story. The organism was not P. thiaminolyticus at all. It was Paenibacillus dendritiformis.

This distinction matters. Accurate species identification shapes understanding of virulence, resistance, and treatment response. And in this case, it revealed how easily these bacteria can be misidentified.

Under the microscope, Paenibacillus species can appear gram-variable, sometimes staining like gram-negative organisms. That ambiguity can delay recognition or lead clinicians down the wrong diagnostic path.

In critically ill infants, time lost can mean brain lost.

The Genetic Clues Hidden Inside the Bacteria

When researchers examined the bacterial genomes, they uncovered a troubling arsenal.

The isolates contained genes encoding a type IV pilus operon, structures associated with bacterial virulence. Previous work has implicated the type IV pilus as a factor in neonatal paenibacilliosis.

They also found multiple β-lactamases, enzymes capable of breaking down β-lactam antibiotics before those drugs can disrupt bacterial cell-wall synthesis. This raises immediate concern about standard antibiotic regimens.

Even more unsettling, genomic analysis detected vancomycin resistance determinants. Although the U.S. strains tested as phenotypically susceptible to vancomycin in the lab, the presence of resistance genes suggests a hidden complexity. A clinician might see laboratory susceptibility and feel reassured—until treatment fails.

Among the genes was thiaminase 1, the enzyme that destroys thiamine. This offers a biologically plausible explanation for how infection leads to brain injury. As thiamine levels drop within brain tissue, neurons become vulnerable. Tissue destruction may arise not only from direct bacterial invasion but also from nutrient depletion.

In these infants, infection may have attacked the brain on multiple fronts at once.

The Uncertain Road of Treatment

Optimal antimicrobial therapy for Paenibacillus dendritiformis meningitis remains undefined.

Whole-genome sequencing shows the presence of β-lactamase genes. These enzymes can neutralize commonly used antibiotics. Routine regimens for neonatal bacteremia and meningitis may not provide adequate coverage.

Some cases associated with more favorable outcomes have involved meropenem combined with thiamine supplementation. This combination attempts to address both bacterial survival and thiamine depletion. Yet even with aggressive treatment, neurologic injury may persist.

Adding to the uncertainty, the detection of vancomycin resistance genes complicates therapeutic decisions. Laboratory testing may suggest susceptibility, but genomic analysis hints at deeper resistance mechanisms. Without whole-genome sequencing or clear clinical failure, these hidden traits may remain undetected.

For physicians standing at the bedside of a seizing infant, these uncertainties are more than academic. They are urgent, practical dilemmas.

Where Does It Come From?

Both infants were born preterm and required care in neonatal intensive care units. The source of infection remains unclear.

Paenibacillus species are commonly found in soil and water. Environmental reservoirs have been proposed. Past observations in Uganda noted associations with rainfall and proximity to large bodies of water. But whether those patterns apply in U.S. settings is uncertain.

In many American cases, environmental explanations appear unlikely.

The bacterium’s route into these fragile bodies remains an open question.

A Quiet Threat Emerging Into View

For years, Paenibacillus was considered an uncommon human pathogen. That perception is shifting.

As more neonatal cases are recognized across multiple states, clinicians are being forced to reconsider. What was once dismissed as a contaminant or laboratory curiosity may in fact represent a clinically significant and potentially underrecognized cause of severe neurologic injury.

The stakes are high. In newborns—especially those born prematurely—the brain is still forming delicate connections. Damage during this window can alter an entire lifetime.

Why This Research Matters

This research changes the conversation around infant meningitis.

It tells clinicians to look again when cultures show unusual gram-variable organisms. It underscores the importance of accurate species identification, potentially through whole-genome sequencing, when clinical deterioration persists. It warns that routine antibiotic regimens may not be enough. It highlights the biological role of thiamine depletion in brain injury and suggests that supplementation may be critical.

Most of all, it urges vigilance.

Early recognition, broader antimicrobial consideration, and timely neurosurgical consultation are not abstract recommendations. They are lifelines. Infections that progress to hydrocephalus, abscess formation, or liquefactive meningoencephalitis leave little room for delay.

These two infants represent more than isolated tragedies. They signal a need for heightened awareness among clinicians who care for the youngest patients. They reveal how a bacterium once thought harmless can cause catastrophic injury. They challenge assumptions about treatment adequacy and diagnostic certainty.

In neonatal intensive care units, every hour matters. Every test matters. Every decision matters.

The story of Paenibacillus dendritiformis in infant meningitis is still unfolding. But one message is already clear: what we fail to recognize can cause profound harm. And the sooner we see it clearly, the better chance we have to protect the most vulnerable brains among us.

Study Details

Danielle Smith et al, Paenibacillus dendritiformis as a Cause of Destructive Meningitis in Infants, NEJM Evidence (2026). DOI: 10.1056/evidpha2500297