Our eyes are more than organs of sight—they are windows through which we experience the colors of the world, the faces of those we love, the beauty of a sunrise, and the written words that connect us to knowledge and imagination. Among the many structures in the eye, the macula plays a silent but essential role in shaping our vision. It is small, but it allows us to read fine print, recognize details, and focus on what matters most.

When this vital part of the retina begins to deteriorate, the world becomes blurred, distorted, or lost at the center. This condition is known as macular degeneration, or more specifically, age-related macular degeneration (AMD)—a progressive eye disease that is one of the leading causes of vision loss worldwide, particularly in people over the age of 50.

Though it cannot steal complete blindness—since peripheral vision often remains intact—it robs the ability to drive, to recognize faces, to read, and to perform the simple acts of independence that give life dignity. To understand macular degeneration is to explore not only its biological causes but also the human journey through its symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments.

Understanding the Macula

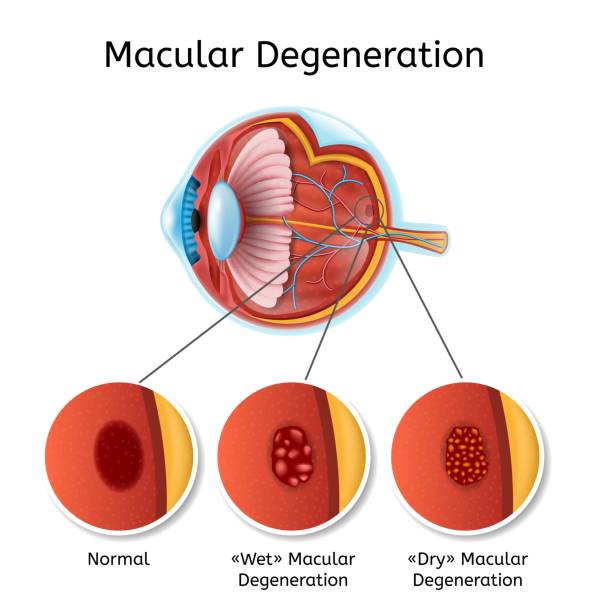

To comprehend the seriousness of macular degeneration, we must first understand the macula itself. The macula is a tiny, oval-shaped area located in the center of the retina, at the back of the eye. It is only about 5 millimeters across, yet it is densely packed with photoreceptor cells—primarily cones—that are responsible for central vision, detail recognition, and color perception.

While the peripheral retina helps us detect movement and navigate our environment, the macula allows us to see what is directly in front of us with clarity. Imagine trying to read without it—the letters would dissolve into a blur. Imagine trying to recognize a loved one’s face—the features would fade into obscurity. The macula is not just a patch of cells; it is the focal point of human sight.

In macular degeneration, this precious area begins to break down. The cells are damaged, waste builds up, and blood vessels may leak or grow abnormally. Over time, vision is distorted or lost at the center, creating a frustrating paradox: you can see the world around you, but not the details that matter most.

Types of Macular Degeneration

There are two primary types of AMD: dry (atrophic) and wet (neovascular or exudative).

Dry Macular Degeneration

This is the more common form, affecting about 80–90% of AMD patients. It progresses slowly as the light-sensitive cells in the macula thin and die. A hallmark feature of dry AMD is the presence of drusen—tiny yellow deposits of cellular waste that accumulate beneath the retina. In early stages, they may not cause noticeable vision changes, but as they grow larger and more numerous, they disrupt the function of the macula, leading to blurred or distorted central vision.

Wet Macular Degeneration

Although less common, wet AMD is more severe and accounts for the majority of cases that result in significant vision loss. It occurs when abnormal blood vessels grow beneath the retina and macula, a process known as choroidal neovascularization. These fragile vessels can leak blood and fluid, causing swelling, scarring, and rapid damage to the macula. Without treatment, wet AMD can cause sudden and profound loss of central vision.

It is important to note that dry AMD can sometimes progress to wet AMD, making regular monitoring essential.

Causes and Risk Factors

Macular degeneration is a multifactorial disease—no single cause explains it fully. Instead, it arises from a combination of genetic predisposition, environmental influences, and aging processes.

The Role of Aging

The most significant risk factor is age. AMD is rare in those under 50 but becomes increasingly common as people grow older. The aging process weakens the body’s ability to repair damage, increases oxidative stress, and alters the metabolism of retinal cells. Over time, these changes compromise the macula’s health.

Genetics and Family History

Genetics play a substantial role. Certain gene variants, such as those in the complement factor H (CFH) gene, increase susceptibility by influencing inflammation and the immune system’s activity in the retina. If a close relative has AMD, the risk is significantly higher.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors

While genetics and aging cannot be changed, lifestyle factors heavily influence the development and progression of AMD:

- Smoking: The most preventable risk factor. Smokers have two to four times the risk of developing AMD compared to non-smokers. Cigarette smoke contributes to oxidative damage and restricts blood flow to the retina.

- Diet: Diets lacking antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and essential nutrients increase susceptibility. Conversely, diets rich in leafy greens, colorful vegetables, and healthy fats may protect the macula.

- Obesity and Sedentary Lifestyle: Both are linked to higher rates of AMD, likely through metabolic and cardiovascular pathways.

- High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease: Vascular health directly affects the retina, making conditions that restrict blood flow detrimental to the macula.

- Light Exposure: Some evidence suggests that lifelong exposure to ultraviolet or blue light may contribute to retinal damage.

Other Contributing Factors

Gender, ethnicity, and eye color also play roles. AMD is more common in women, perhaps due to longer life expectancy, and is more prevalent in Caucasians than in African or Asian populations. People with lighter eye colors may be at greater risk due to less pigment protection against light damage.

Symptoms: How Vision Changes

One of the cruelest aspects of macular degeneration is its subtle onset. Early stages often produce no noticeable symptoms, making regular eye exams critical. As the disease progresses, symptoms emerge, often first in one eye and later in both.

Common Symptoms

- Blurriness in central vision: Straight lines may appear wavy, or letters may seem faded.

- Dark or empty spots: A gray, black, or blank area may appear at the center of vision.

- Difficulty with detail: Reading, sewing, or recognizing faces becomes harder.

- Color distortion: Colors may seem less vivid or harder to distinguish.

- Poor adaptation to low light: Night driving or moving from bright to dim spaces becomes challenging.

Emotional Impact

Beyond the physical symptoms, macular degeneration carries an emotional weight. Losing the ability to read, drive, or recognize loved ones can bring frustration, anxiety, and depression. For many, it feels like losing independence and identity. Support, education, and counseling are vital in helping patients cope with these psychological effects.

Diagnosis: Peering Into the Retina

Because early AMD may not cause symptoms, routine eye examinations are essential for detection. Eye doctors use several tools and techniques to diagnose macular degeneration and distinguish between dry and wet forms.

Dilated Eye Exam

The most basic step is a dilated eye exam. After dilating the pupils with eye drops, the doctor examines the retina with a special lens, looking for drusen, pigment changes, or leaking blood vessels.

Amsler Grid Test

Patients may be asked to look at an Amsler grid—a simple square grid with a central dot. People with AMD may notice that lines appear wavy, distorted, or missing when focusing on the dot.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique that provides cross-sectional images of the retina. It can reveal thinning of retinal layers in dry AMD or fluid accumulation in wet AMD, making it one of the most valuable tools for monitoring disease progression.

Fluorescein Angiography

For suspected wet AMD, fluorescein angiography may be used. A fluorescent dye is injected into the bloodstream, and as it travels through retinal vessels, a special camera takes images to reveal abnormal blood vessel growth or leakage.

Genetic Testing and Biomarkers

Although not routine, genetic testing can identify high-risk individuals. Research is also underway to develop blood-based biomarkers that could help in early detection.

Treatment: Slowing the Progress, Saving Vision

At present, there is no complete cure for macular degeneration. However, significant advances in treatment—especially for wet AMD—have transformed a once hopeless diagnosis into a manageable condition.

Treating Dry AMD

For dry AMD, no medication or surgery can fully restore lost vision, but progression may be slowed through nutritional and lifestyle interventions.

- AREDS Supplements: Large clinical trials known as AREDS (Age-Related Eye Disease Study) showed that high doses of vitamins C and E, zinc, copper, lutein, and zeaxanthin can reduce the risk of advanced AMD in people with intermediate disease.

- Dietary Approaches: A Mediterranean-style diet rich in vegetables, fruits, fish, and olive oil appears protective.

- Lifestyle Changes: Quitting smoking, exercising, and managing cardiovascular health reduce risk.

Treating Wet AMD

Wet AMD requires urgent treatment to preserve central vision.

- Anti-VEGF Therapy: The most revolutionary treatment is anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections. Drugs such as ranibizumab, bevacizumab, and aflibercept block VEGF, a protein that stimulates abnormal blood vessel growth. Regular injections directly into the eye can halt or even reverse vision loss in many patients.

- Photodynamic Therapy: This involves injecting a light-sensitive drug into the bloodstream, which accumulates in abnormal vessels. A laser is then used to activate the drug, destroying the vessels without harming surrounding tissue.

- Laser Photocoagulation: Once common, this method uses a high-energy laser to seal leaking vessels but has largely been replaced by safer and more effective anti-VEGF therapy.

Low Vision Aids and Rehabilitation

For those with advanced vision loss, tools such as magnifying devices, high-contrast materials, and specialized glasses can help maintain independence. Vision rehabilitation programs teach patients adaptive strategies, such as using peripheral vision more effectively.

Living with Macular Degeneration

Macular degeneration is not only a medical condition but also a life-changing experience. Patients must learn to navigate a world where central vision is unreliable. This requires resilience, adaptation, and support from family, friends, and healthcare professionals.

Technology plays an important role. Screen readers, audiobooks, and voice-activated devices restore access to information. Large-print books, high-contrast lighting, and smartphone accessibility features make daily tasks easier. Social support groups provide encouragement and reduce isolation.

Prevention: Protecting the Window of Vision

While not all cases can be prevented, there are powerful steps individuals can take to reduce their risk or slow progression:

- Stop smoking completely.

- Eat a diet rich in leafy greens, berries, fish, and nuts.

- Protect eyes from excessive sunlight with UV-blocking sunglasses.

- Exercise regularly and maintain healthy blood pressure and cholesterol.

- Schedule regular eye exams, especially after age 50.

The Future of Treatment and Research

Science is rapidly advancing in the fight against AMD. New therapies are being tested that could change the landscape of care:

- Long-acting anti-VEGF injections or implantable reservoirs to reduce treatment burden.

- Gene therapy to modify the expression of proteins involved in vessel growth.

- Stem cell therapy to replace damaged retinal cells.

- Neuroprotective drugs that shield retinal cells from oxidative damage.

- Artificial vision technologies—retinal implants and bionic eyes—are being explored for severe cases.

The hope is not just to slow macular degeneration but to one day reverse it entirely, restoring the gift of sight.

Conclusion: Holding on to the Light

Macular degeneration is more than a medical diagnosis—it is a challenge to the way we experience life itself. It begins silently, then slowly steals the details we often take for granted. But it is not without hope. Through early detection, lifestyle choices, and advanced treatments, millions of people continue to live with clarity, dignity, and independence.

At its core, macular degeneration reminds us of the fragility of sight, but also of human resilience. Even as the macula falters, the will to adapt, to love, and to live fully remains unshaken. And with science advancing each year, the horizon glows with the possibility that one day, blindness from macular degeneration will be a story of the past, not the future.