Among all the conditions that affect human vision, few are as insidious and feared as glaucoma. Known widely as the “silent thief of sight,” glaucoma is not just a disease of the eye but a global public health challenge that quietly robs millions of people of their vision. It progresses stealthily, often without pain or warning, and by the time symptoms are recognized, the damage may already be permanent.

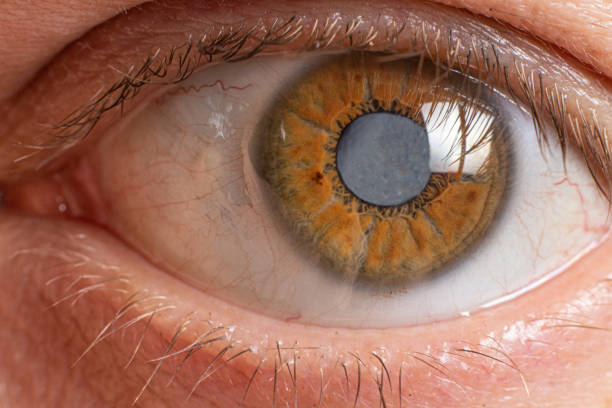

To understand glaucoma is to appreciate both the delicate anatomy of the eye and the profound impact vision loss has on human life. Our eyes are more than organs; they are windows through which we experience the world, connect with loved ones, and navigate daily existence. When glaucoma enters this picture, it disrupts not just vision but quality of life, independence, and emotional well-being.

This article takes a deep journey into the nature of glaucoma—its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments—blending scientific accuracy with human understanding. By the end, you will see why glaucoma is both a challenge and an opportunity: a challenge because it threatens sight without mercy, and an opportunity because early diagnosis and modern treatment can protect vision for a lifetime.

What Exactly Is Glaucoma?

Glaucoma is not a single disease but a group of eye conditions that damage the optic nerve—the critical cable that carries visual information from the eye to the brain. The optic nerve is composed of over a million nerve fibers, and when these fibers are damaged, blind spots begin to form in the field of vision. Left untreated, glaucoma can lead to irreversible blindness.

The most common culprit behind glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), which occurs when the fluid inside the eye, called aqueous humor, does not drain properly. This buildup of fluid creates pressure that slowly, and often silently, damages the optic nerve. Yet glaucoma can also occur in people with normal eye pressure, proving that the disease is more complex than pressure alone.

The Global Burden of Glaucoma

Glaucoma is one of the leading causes of irreversible blindness worldwide. According to the World Health Organization, it affects more than 70 million people globally, and nearly half of them are unaware they even have it. The reason? Glaucoma often progresses without symptoms until advanced stages.

The burden of glaucoma is not just medical but deeply social and economic. Blindness or severe vision loss impacts employment, independence, mental health, and quality of life. Families must adjust to caregiving roles, and healthcare systems face long-term challenges in supporting those who have lost their vision. In this way, glaucoma is both a medical condition and a societal issue.

Causes of Glaucoma

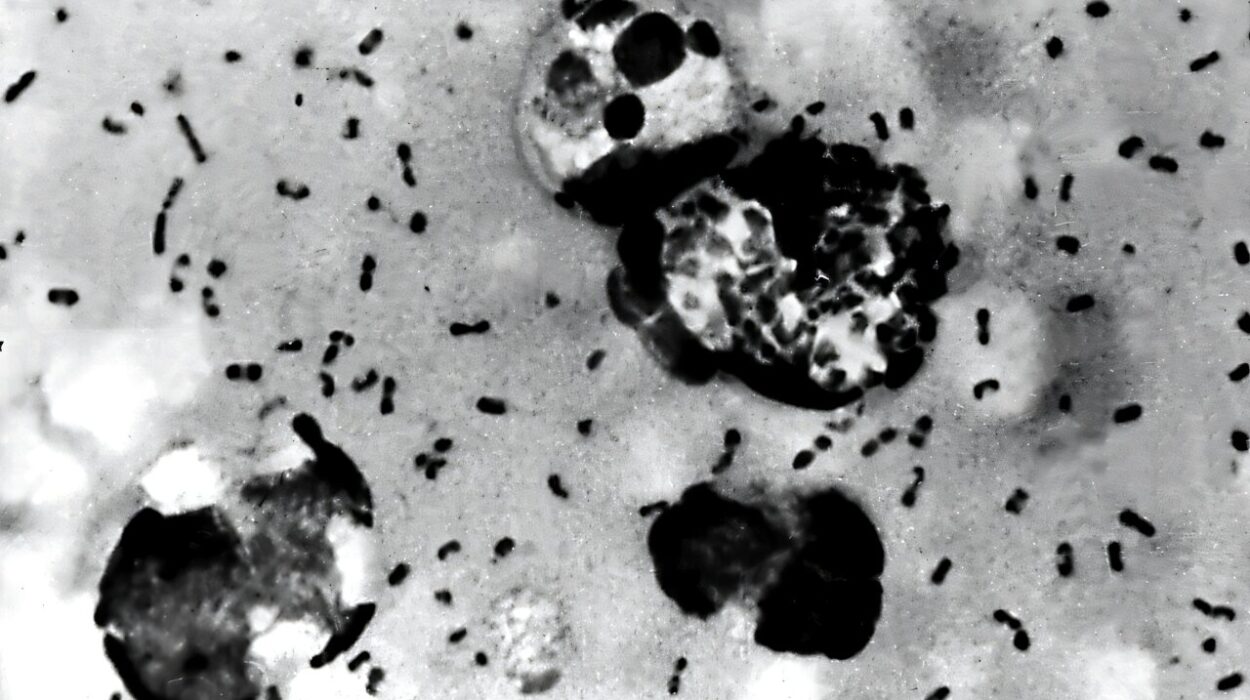

To understand what causes glaucoma, it helps to know how the eye maintains balance. The aqueous humor, a clear fluid, circulates through the eye to nourish tissues and maintain shape. Normally, this fluid drains out through a tiny mesh-like channel called the trabecular meshwork. When this drainage system is blocked or impaired, fluid builds up, raising intraocular pressure.

But high eye pressure is not the only cause. Other factors—including genetics, age, trauma, and even vascular health—can play critical roles.

Elevated Intraocular Pressure (IOP)

The most significant risk factor for glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure. Normal IOP ranges from 10 to 21 millimeters of mercury (mmHg). When pressure rises above this range, the risk of optic nerve damage increases. However, not all people with high IOP develop glaucoma, and some people with normal IOP do—a condition called normal-tension glaucoma.

Genetic Factors

Glaucoma often runs in families. Specific genes have been linked to certain types of glaucoma, such as mutations in the MYOC gene associated with juvenile open-angle glaucoma. Genetics can influence how the eye regulates fluid flow and responds to pressure, making hereditary predisposition an important factor.

Age

The risk of glaucoma increases with age. People over 40 are at higher risk, and prevalence rises significantly after 60. This connection may be due to natural changes in the eye’s drainage system, blood flow, and tissue resilience.

Ethnicity

Certain ethnic groups are at higher risk. African Americans, for instance, are more likely to develop open-angle glaucoma and at younger ages than Caucasians. People of Asian descent are more prone to angle-closure glaucoma, while those of Hispanic origin show increased risk with aging.

Medical Conditions and Eye Injuries

Conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease increase the likelihood of glaucoma. Long-term use of corticosteroids can also raise IOP. Eye trauma, whether from sports injuries or accidents, can disrupt the drainage system and cause secondary glaucoma.

Vascular Factors

In some cases, glaucoma develops despite normal IOP, suggesting that reduced blood flow to the optic nerve may be a cause. Vascular dysregulation, such as abnormal blood pressure fluctuations or compromised circulation, can starve the optic nerve of oxygen, leading to damage.

Types of Glaucoma

Glaucoma is not a one-size-fits-all disease. Several forms exist, each with unique characteristics, causes, and treatment approaches.

Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma (POAG)

This is the most common form, especially in Western countries. It develops slowly when the drainage canals become clogged over time, causing gradual pressure buildup. POAG is painless and progresses silently, making regular eye exams essential for early detection.

Angle-Closure Glaucoma

Here, the angle between the iris and cornea (where fluid normally drains) becomes blocked suddenly, causing a rapid rise in IOP. This is a medical emergency, as it can lead to sudden vision loss if untreated. Symptoms may include severe eye pain, headache, nausea, halos around lights, and blurred vision.

Normal-Tension Glaucoma (NTG)

In NTG, optic nerve damage occurs despite normal IOP. This form highlights that pressure is not the only factor. Vascular issues and heightened sensitivity of the optic nerve may play key roles.

Secondary Glaucoma

This type arises as a complication of another condition—such as eye injury, uveitis (inflammation), tumors, or prolonged steroid use. The underlying cause must be treated along with the glaucoma.

Congenital Glaucoma

Rare but severe, congenital glaucoma affects infants and young children. It results from improper development of the eye’s drainage canals before birth. Symptoms may include cloudy eyes, excessive tearing, and sensitivity to light. Prompt surgery is usually necessary to prevent blindness.

Symptoms of Glaucoma

One of the most challenging aspects of glaucoma is its stealthy progression. In early stages, most people notice no symptoms at all. Vision loss begins at the periphery, creating blind spots that the brain often compensates for unconsciously.

In advanced stages, central vision becomes affected, making reading, driving, or recognizing faces difficult. By then, significant and irreversible damage has occurred.

Open-Angle Glaucoma Symptoms

- Gradual loss of peripheral vision, often unnoticed until advanced.

- Tunnel vision in later stages.

Angle-Closure Glaucoma Symptoms

- Severe eye pain and headache.

- Blurred vision or sudden vision loss.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Halos around lights.

- Red eyes.

Congenital Glaucoma Symptoms

- Cloudy cornea.

- Excessive tearing.

- Light sensitivity.

The tragedy of glaucoma lies in its silence—most people do not realize they are affected until vision is already compromised.

Diagnosis of Glaucoma

Early detection is the single most powerful weapon against glaucoma. Because the disease often develops without symptoms, regular comprehensive eye exams are crucial, especially for those at higher risk.

A typical glaucoma evaluation includes:

Measuring Intraocular Pressure (Tonometry)

A tonometer measures eye pressure, often using a small puff of air or a gentle probe. While useful, this test alone cannot diagnose glaucoma, as damage can occur at normal pressures.

Assessing the Optic Nerve (Ophthalmoscopy)

The ophthalmologist examines the optic nerve for signs of damage. A healthy nerve has a specific color and contour; changes in shape or cupping suggest glaucoma.

Visual Field Test (Perimetry)

This test maps peripheral vision to detect blind spots caused by optic nerve damage. Patients look straight ahead while responding to lights appearing in different parts of their vision.

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT)

OCT uses light waves to capture detailed images of the retina and optic nerve fibers, allowing precise monitoring of damage over time.

Gonioscopy

A special lens allows the doctor to view the drainage angle between the iris and cornea, helping distinguish between open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma.

Comprehensive diagnosis combines these tests, repeated over time, to confirm progression and guide treatment.

Treatment of Glaucoma

Though glaucoma cannot be cured and lost vision cannot be restored, treatment can slow or halt progression. The goal of therapy is to lower intraocular pressure and preserve remaining vision.

Medications

Eye drops are often the first line of treatment. They work by either reducing the production of aqueous humor or improving its drainage. Common classes include prostaglandin analogs, beta-blockers, alpha agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Oral medications may be used if eye drops are insufficient.

Laser Therapy

Laser treatments can enhance fluid drainage or reduce fluid production. For open-angle glaucoma, laser trabeculoplasty is often used. For angle-closure glaucoma, laser peripheral iridotomy creates a tiny hole in the iris to relieve pressure.

Surgical Procedures

When medications and laser therapy are not enough, surgery may be necessary. Trabeculectomy, a common surgery, creates a new drainage pathway. Glaucoma drainage devices (tiny tubes) can also be implanted. Minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) are newer techniques offering shorter recovery times with fewer risks.

Lifestyle and Supportive Care

While treatment focuses on medical interventions, lifestyle also matters. Protecting the eyes from injury, maintaining regular medical checkups, exercising safely, and adhering to prescribed medications all contribute to preserving vision. Emotional support and counseling may also help patients cope with the psychological burden of chronic disease.

Living with Glaucoma

Being diagnosed with glaucoma can feel overwhelming. Fear of blindness, medication routines, and frequent appointments create stress. Yet with modern treatments, many patients live full lives without losing vision. The key lies in adherence—taking medications consistently, attending follow-up exams, and reporting any changes in vision.

Support groups and patient education play vital roles in helping people adapt. Sharing experiences reduces isolation, while learning more about the disease empowers individuals to take control of their care.

Prevention and Early Detection

Glaucoma cannot always be prevented, but early detection dramatically improves outcomes. Regular eye exams are essential, particularly for people over 40, those with a family history, or members of high-risk ethnic groups.

Protective steps include:

- Scheduling comprehensive eye exams.

- Managing systemic conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

- Wearing protective eyewear during sports or risky activities.

- Avoiding overuse of corticosteroids without medical supervision.

These simple steps can make the difference between lifelong vision and irreversible blindness.

The Future of Glaucoma Care

Research into glaucoma is advancing rapidly. Scientists are exploring new drugs that protect the optic nerve directly, rather than just lowering eye pressure. Stem cell therapies may one day regenerate damaged nerve fibers. Genetic studies aim to identify at-risk individuals earlier, enabling preventive strategies before vision loss begins.

Artificial intelligence is also revolutionizing diagnosis by analyzing optic nerve images with unprecedented accuracy. Combined with telemedicine, these innovations promise wider access to care, especially in underserved areas.

Conclusion: Guarding the Window to the World

Glaucoma is a formidable adversary—a disease that creeps silently, stealing vision without notice. Yet it is also a condition that teaches resilience and the power of awareness. With early detection, modern medicine, and a proactive approach, blindness from glaucoma can often be prevented.

To live with healthy eyes is to live with open windows to the world. Understanding glaucoma, spreading awareness, and supporting research are not just medical duties but human responsibilities. For sight is more than vision—it is memory, independence, connection, and joy. And preserving it is one of the greatest gifts we can give ourselves and others.