The human story has always been a story of movement—of daring voyages, restless curiosity, and the urge to see what lies beyond the known world. From the first canoes that sliced through the Pacific to the caravels that crossed the Atlantic, exploration has defined who we are. Yet, there are limits to where courage and ingenuity can take us—limits drawn not by imagination, but by nature itself.

A recent study published in the Journal of Coastal and Island Archaeology by Dr. Thomas Leppard and his colleagues, John Cherry and Atholl Anderson, reexamines one of the last untouched frontiers of pre-European exploration: the frigid waters south of the 50th parallel. Their work probes an intriguing question—did Indigenous peoples of the Southern Hemisphere ever venture deep into the Southern Ocean before European contact?

The answer, according to their meticulous investigation, is no. But it’s a “no” that speaks not of weakness or ignorance, but of wisdom—a recognition of nature’s limits, and of the immense environmental risk such journeys would have entailed.

The Relentless Southern Ocean

Below the 50th parallel, the Earth becomes something altogether different. The Southern Ocean is not a place of gentle breezes or tranquil bays. It is a region defined by raw power and unending hostility. Here, colossal waves rise and fall in endless succession, whipped by ferocious winds that circle the planet unimpeded. Icebergs drift like sleeping giants, and the air carries the sting of eternal winter.

The islands scattered across this ocean—the Auckland, Campbell, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands—are bleak, treeless, and inhospitable. Their landscapes are home only to seabirds, seals, and the occasional human research station. Even today, with steel ships and modern technology, the Southern Ocean commands both respect and fear.

Before Europeans arrived, it was long believed that these islands had never known human footsteps. Only Tierra del Fuego, at the tip of South America, was known to host Indigenous peoples who braved the harsh southern seas. But in recent years, new claims have emerged: could it be that Polynesian or South American voyagers had reached these remote places long before European sails appeared on the horizon?

Legends of Ice and Navigation

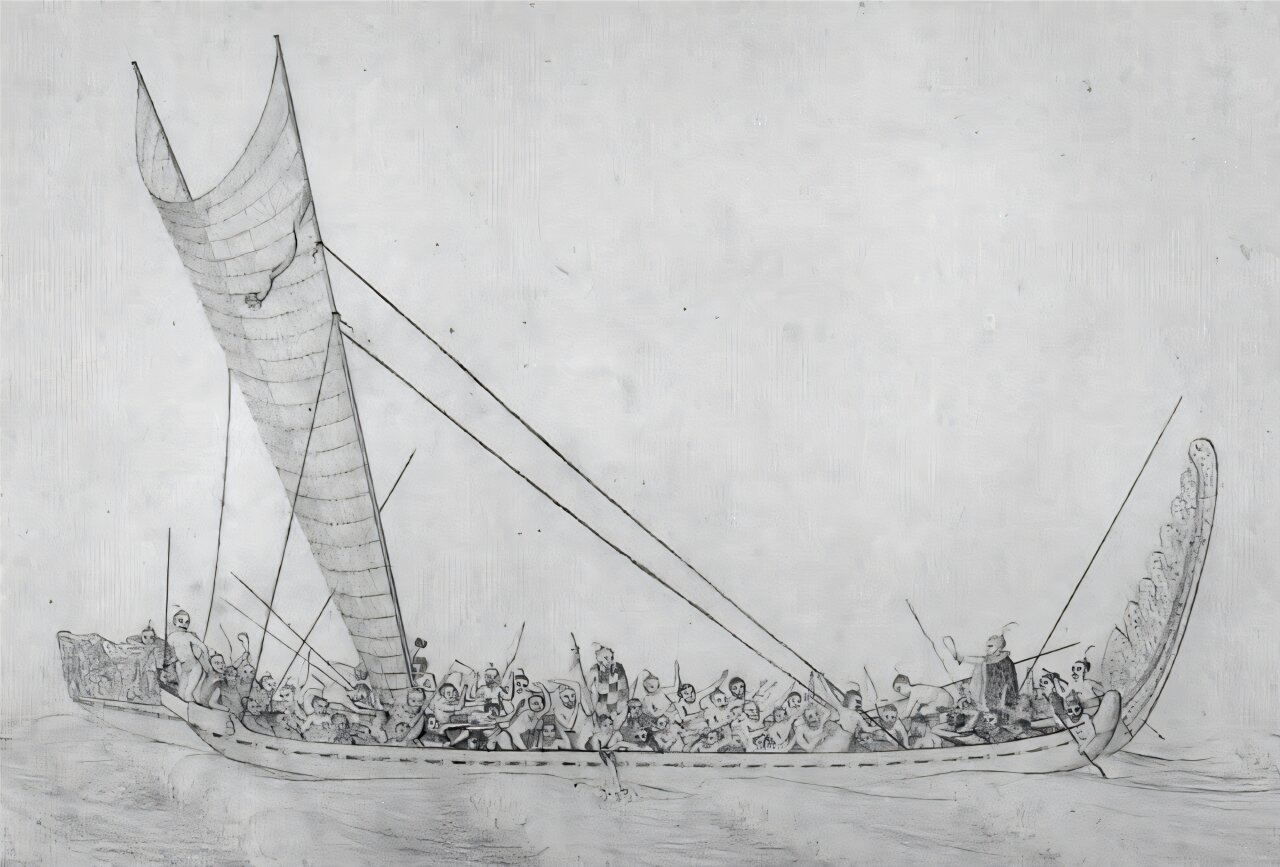

Among the Māori and other Polynesian peoples, seafaring skill was not just a craft—it was an art, a spiritual calling. Their ancestors crossed vast oceans guided only by stars, wind, and the rhythm of waves. They reached and settled islands scattered across the Pacific, forming one of the most remarkable maritime networks in human history.

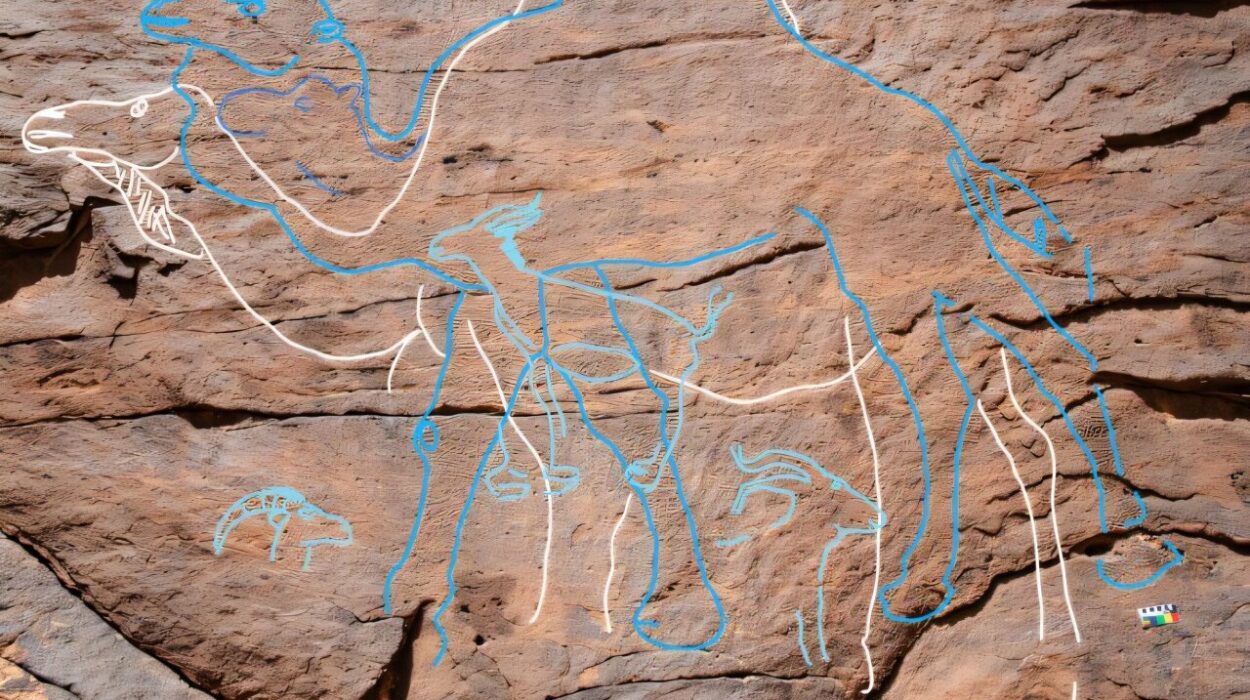

One particular legend, recorded in 1899 by Stephenson Percy Smith, tells of a great navigator named Ui-te-Rangiora, a Rarotongan who supposedly sailed into the “tai-uka,” or “frozen sea.” Smith’s interpretation of the term led him to believe that Ui-te-Rangiora had voyaged to the icy realms of Antarctica centuries before Europeans. But as linguists have since pointed out, the term might not have referred to ice at all. The “white sea” described in the tale could have meant a foaming, turbulent ocean—white not with frost, but with the churning of waves.

Dr. Leppard and his colleagues approached such stories with both respect and caution. Oral traditions, after all, are powerful cultural expressions, but they are not always literal historical records. To truly understand whether ancient Polynesians or South Americans reached the far south, one must look for the silent witnesses of time—archaeological evidence buried beneath moss and ice.

The Māori and the Edge of the World

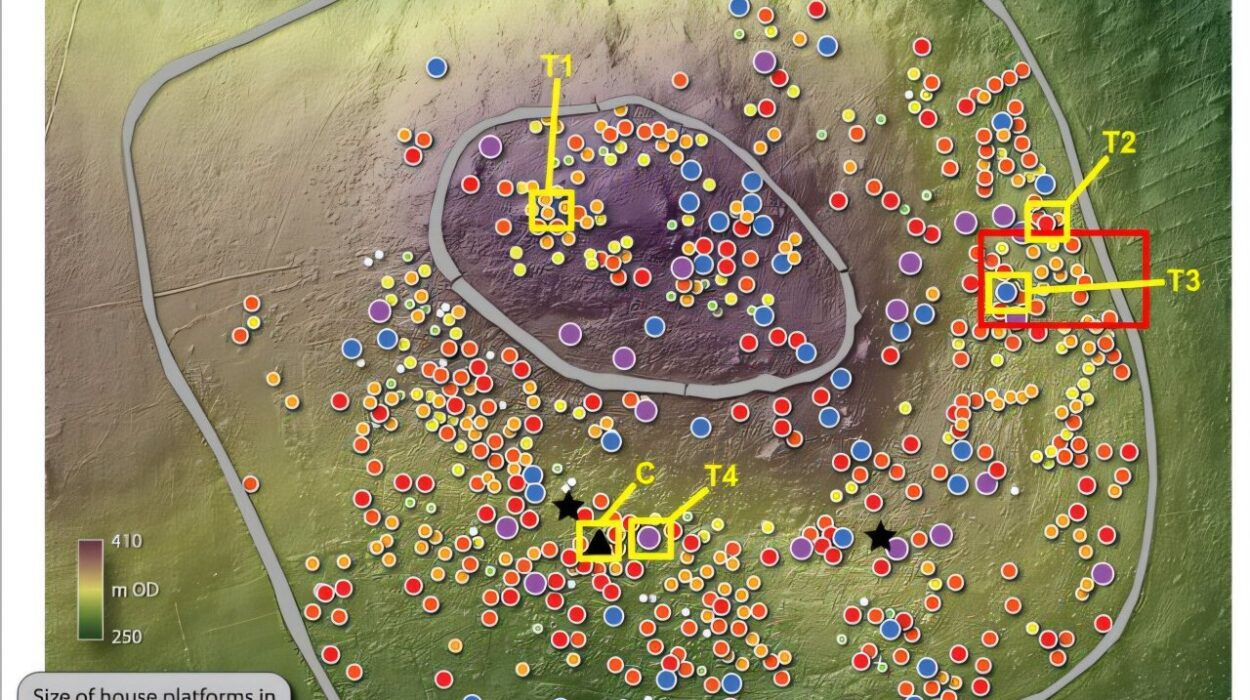

Archaeology tells us that the Māori, descendants of Polynesian voyagers, reached New Zealand around 1200 AD. They later expanded to the nearby Chatham Islands and, remarkably, to Enderby Island—the northernmost of the Auckland Islands, lying just below the 50th parallel. Evidence suggests that Enderby was briefly inhabited between 1300 and 1400 AD, before being abandoned as the climate worsened.

Enderby Island today is a desolate place. Temperatures hover around 8°C, rain falls nearly 300 days a year, and sunlight is scarce. Living there required extraordinary resilience and adaptation. The Māori settlers likely relied on local seals and birds for food, but even so, survival would have been difficult. To venture farther south, into the even colder and more isolated islands, would have bordered on the impossible.

The researchers point out a crucial logistical challenge: beyond the Auckland Islands, there was no source of wood for repairing canoes or building shelters. Māori voyaging vessels, though incredibly advanced for their time, depended on materials like flax and timber from New Zealand. In the subantarctic, neither resource existed in abundance. Bark or sealskin could not substitute for sturdy wood in ship repairs, making any return journey perilous.

Thus, while the Māori proved themselves capable of extraordinary seafaring, the natural barriers of the Southern Ocean drew a definitive line—a line that even their skill and courage could not cross.

South American Voyagers and the Cold Frontier

If not the Māori or Rarotongans, could the Indigenous peoples of South America have reached the icy islands of the South Atlantic? The study also examined this possibility, turning its attention to the Fuegians and other maritime cultures of southern South America.

The peoples of Tierra del Fuego were expert seafarers in their own right. Using small bark canoes, they navigated the labyrinthine channels of the Fuegian archipelago, hunting seals, fishing, and trading between islands. Yet, their vessels were not built for the open ocean. They were narrow, shallow, and easily swamped by waves—perfect for sheltered waters, but deadly in the storm-lashed Southern Ocean.

Some artifacts—stone tools, bone harpoons, and even human remains—have been found on islands like the Falklands and South Georgia. But upon closer inspection, all these traces date to post-European times. Many were left by Indigenous people who had been relocated by missionaries or by workers during early sealing expeditions. One notable example is the transfer of 150 Fuegians to Pebble Island in 1855 by the Patagonian Missionary Society. There, they made stone tools and whalebone harpoons, artifacts later mistaken for signs of ancient habitation.

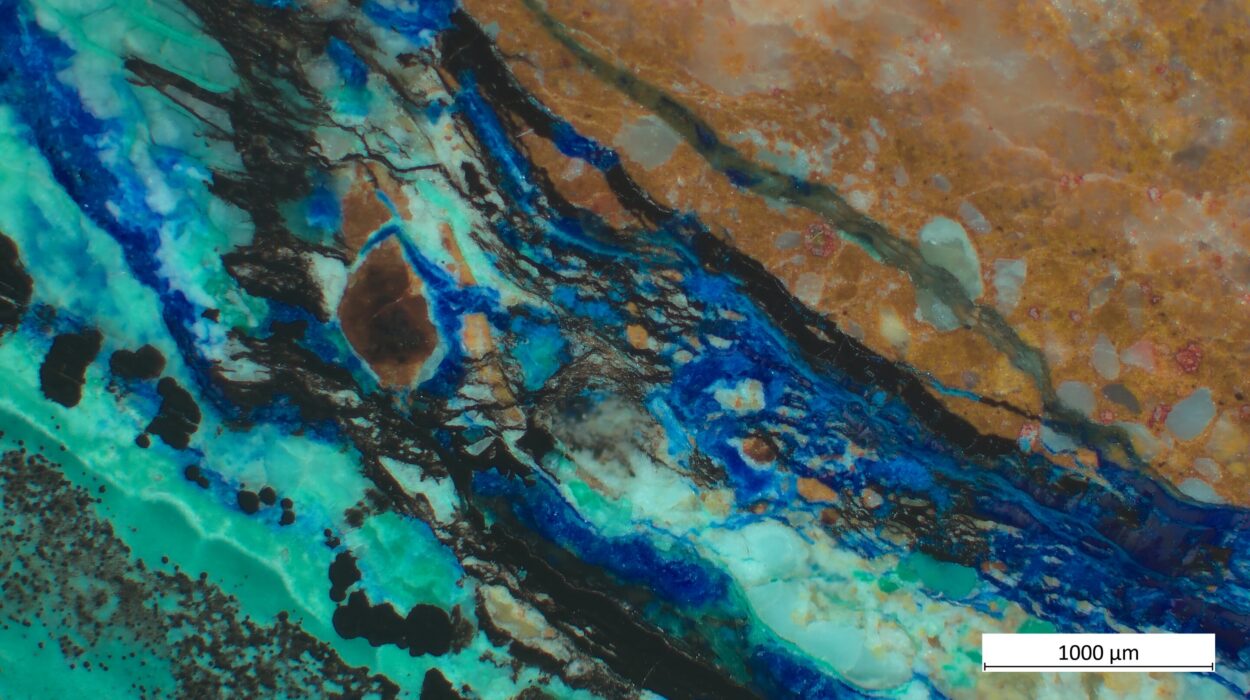

In short, no evidence exists of pre-European contact between the Indigenous peoples of South America and the subantarctic islands. The absence of such evidence is especially telling given how well artifacts tend to preserve in cold climates.

As Dr. Leppard explains, “In these environments, we’d actually expect organic materials to preserve better. Cold conditions inhibit decay, and since these islands have seen little modern disturbance, we would expect any archaeological record to be intact. The absence of one speaks volumes.”

The Wisdom of Restraint

The researchers’ conclusion is as humbling as it is profound. The lack of evidence for pre-European voyages below the 50th parallel does not diminish the seafaring brilliance of Indigenous peoples. On the contrary, it highlights their deep understanding of the environment. These were societies that knew the ocean intimately. They read its moods, its winds, its dangers. They understood where life could thrive—and where survival would become impossible.

The decision not to voyage farther south was not an admission of weakness but a testament to judgment. As Dr. Leppard and his co-authors suggest, such journeys would have been maladaptive—risky, unsustainable, and likely fatal. The people who mastered the seas knew when to push the limits of possibility, and when to honor the natural boundaries set by the Earth itself.

Beyond the Edge of History

The Southern Ocean remains, even today, one of the most formidable barriers on the planet. Its islands are still largely uninhabited, their silence broken only by the cries of seabirds and the roar of waves. Yet, in that silence lies a reminder of human endurance and humility.

The story told by Leppard and his team is not one of absence—it is one of awareness. The Indigenous navigators of the Southern Hemisphere achieved some of the greatest maritime feats in history, settling vast oceanic territories long before European maps were even drawn. Their knowledge of the sea was intuitive, spiritual, and scientific all at once. But the deep south was a place even they respected—a realm not meant for habitation, but for reverence.

The Continuing Search

Though the study found no evidence of pre-European voyages into the far Southern Ocean, its authors are not closing the book. On the contrary, they invite further exploration, further testing of their conclusions. “While we’re not planning another collaborative paper on the Antarctic in the near future,” says Dr. Leppard, “we look forward to continuing to work on issues of colonization, seagoing, and island adaptations.”

Science thrives on challenge, on the willingness to be proven wrong. Perhaps one day, buried beneath Antarctic moss or sealed within ice, a discovery will emerge that reshapes this story again. Until then, the Southern Ocean remains both a mystery and a mirror—reflecting the limits of human reach and the vastness of the world that still lies beyond it.

More information: Thomas P. Leppard et al, Did Indigenous long-distance voyaging occur below 50°S?, Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/15564894.2025.2549845