Depression is more than just sadness. It is a heavy, relentless state of mind and body that can strip the color from life, making even the simplest tasks—getting out of bed, eating a meal, speaking with a friend—feel like insurmountable challenges. It is a condition that reaches into the core of a person’s being, often leaving them feeling empty, hopeless, or disconnected from the world around them.

Yet depression is not a sign of weakness, nor is it a flaw of character. It is a complex medical condition that arises from an interplay of biology, psychology, and environment. Anyone, regardless of age, gender, or social status, can be affected. Millions of people worldwide live with depression, making it one of the most pressing public health concerns of our time.

To understand depression fully, we must explore its causes, recognize its symptoms, uncover how it is diagnosed, and carefully examine the treatments that can help those who suffer rediscover light and meaning in life.

What is Depression?

Depression, clinically known as major depressive disorder (MDD), is classified as a mood disorder. It profoundly affects how a person feels, thinks, and behaves. Unlike ordinary sadness, which is a normal emotional response to life’s difficulties, depression lingers for weeks, months, or even years. It disrupts daily functioning and can alter both mental and physical health.

At its most severe, depression can be life-threatening, contributing to suicidal thoughts or behaviors. But it is also highly treatable, especially when recognized early and managed with comprehensive care.

Depression is not uniform. Some people may experience it as a constant, unshakable sadness; others may feel numb or detached. For some, it manifests primarily as physical symptoms—aches, fatigue, changes in sleep or appetite. This variability makes depression both fascinating and challenging to treat.

The Causes of Depression

Depression does not emerge from a single source. Instead, it is the result of a delicate—and sometimes dangerous—interplay between genetic vulnerability, brain chemistry, life experiences, and environmental factors.

Biological and Genetic Factors

Research consistently shows that depression has a biological foundation. Studies of twins and families suggest that genetic inheritance plays a role: people with close relatives who suffer from depression are more likely to experience it themselves. However, no single “depression gene” has been identified. Instead, multiple genes may increase vulnerability when combined with environmental stress.

On a neurological level, depression is linked to imbalances in brain chemistry, particularly involving neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. These chemical messengers regulate mood, energy, and pleasure. Disruptions in their function may contribute to the emotional and physical symptoms of depression.

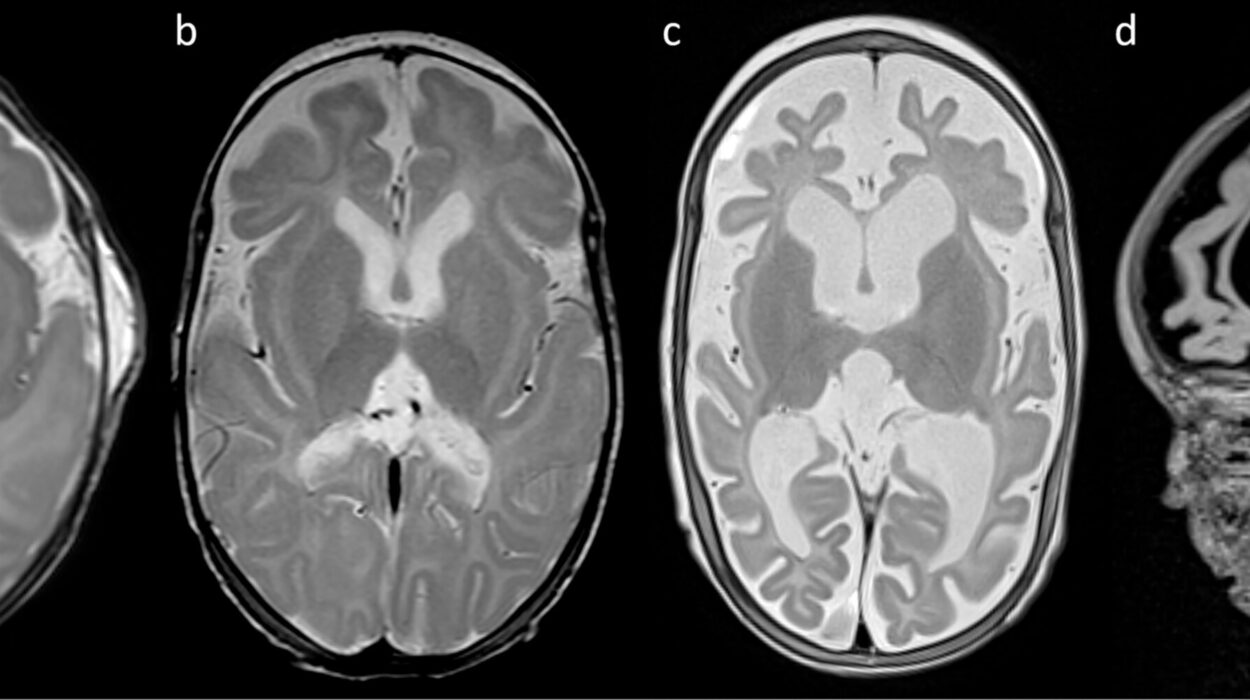

Additionally, brain imaging studies reveal structural and functional differences in people with depression. The hippocampus, which is vital for memory and emotional regulation, often appears smaller. The prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and control of emotions, may show reduced activity.

Psychological and Emotional Triggers

Certain personality traits—such as high sensitivity, perfectionism, or chronic pessimism—can increase the risk of developing depression. Traumatic experiences, including childhood abuse, neglect, or significant losses, may leave lasting imprints on the brain and psyche, making individuals more vulnerable to future depressive episodes.

Stress is another major contributor. While short-term stress can motivate action, chronic stress overwhelms the body’s systems, disrupting hormone regulation and weakening resilience. The stress hormone cortisol, when elevated over long periods, can damage brain structures associated with mood regulation.

Social and Environmental Influences

Depression also thrives in environments marked by instability, poverty, discrimination, or violence. Social isolation, lack of supportive relationships, and exposure to persistent hardship can deepen vulnerability.

Life transitions—such as divorce, job loss, or the death of a loved one—often act as triggers. In some cases, even seemingly positive changes, like moving to a new city or starting a new career, can be destabilizing and contribute to depressive episodes.

The Symptoms of Depression

Depression is not one-size-fits-all. Symptoms vary from person to person, in severity and expression. Some people may appear outwardly functional, while inside they are battling profound despair. Others may struggle to maintain even the simplest routines.

Emotional Symptoms

The hallmark of depression is persistent sadness, but the emotional spectrum is broader:

- Feelings of hopelessness or helplessness—a sense that nothing will ever improve.

- Loss of interest or pleasure (anhedonia) in activities once enjoyed, from hobbies to socializing.

- Excessive guilt or worthlessness, often with harsh self-criticism.

- Irritability and frustration, even over minor matters.

Cognitive Symptoms

Depression affects the way people think:

- Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions.

- Negative thought patterns, including rumination or self-blame.

- Distorted perceptions of reality, such as believing one is a burden to others.

Physical Symptoms

Depression is not only mental; it manifests in the body:

- Changes in appetite—leading to weight gain or loss.

- Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, early waking, or oversleeping.

- Low energy and fatigue, often described as feeling “weighed down.”

- Physical aches and pains, such as headaches or digestive problems, without clear medical causes.

Severe Symptoms

In its most dangerous form, depression can include:

- Thoughts of death or suicide.

- Self-harming behaviors.

- Psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions (in cases of severe depression).

How Depression is Diagnosed

Unlike many physical illnesses, there is no blood test or brain scan that can definitively diagnose depression. Instead, diagnosis relies on careful clinical evaluation by healthcare professionals.

Clinical Interviews

A doctor or mental health professional typically conducts a detailed interview, asking about:

- Duration and severity of symptoms.

- Impact on daily functioning.

- Family history of mental illness.

- Possible triggers or recent life events.

Diagnostic Criteria

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) outlines criteria for major depressive disorder. To receive a diagnosis, a person must experience at least five symptoms (including either depressed mood or loss of interest/pleasure) for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.

Differential Diagnosis

Because depression shares symptoms with other conditions—such as thyroid disorders, vitamin deficiencies, or medication side effects—doctors may order physical exams or lab tests to rule out medical causes. Co-occurring disorders, such as anxiety or substance abuse, are also evaluated, as they often complicate the clinical picture.

Treatment Options for Depression

The good news is that depression is treatable. With the right approach, many people experience significant improvement, and some achieve complete remission. Treatment usually combines multiple strategies tailored to the individual.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy, or “talk therapy,” provides a safe space for individuals to explore thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) helps people identify and reframe negative thought patterns, replacing them with healthier perspectives.

- Interpersonal Therapy (IPT) focuses on improving relationships and social functioning, which can reduce depressive symptoms.

- Psychodynamic Therapy explores unconscious conflicts and past experiences that may contribute to depression.

Therapy not only reduces symptoms but also builds resilience, equipping people with coping strategies for future challenges.

Medication

Antidepressants can rebalance brain chemistry. Common classes include:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) like fluoxetine and sertraline.

- Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) such as venlafaxine.

- Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) and Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs), older classes used less frequently due to side effects.

Medications often take several weeks to show effects and may require adjustments to find the right drug and dose.

Lifestyle Interventions

Daily habits play a powerful role in recovery:

- Exercise improves mood by boosting endorphins and promoting brain plasticity.

- Healthy diet supports brain function and energy.

- Sleep hygiene restores balance to the body and mind.

- Stress reduction practices, such as meditation or yoga, reduce cortisol levels.

Advanced Treatments

For severe or treatment-resistant depression, other options include:

- Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)—an effective, though sometimes stigmatized, treatment for severe cases.

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)—a non-invasive brain stimulation technique.

- Ketamine infusion therapy—a newer approach showing rapid relief for some individuals.

Social Support

Isolation deepens depression, while connection heals. Support groups, family therapy, or simply spending time with trusted friends can provide the encouragement and perspective needed for recovery.

Living with Depression: The Human Experience

Beyond clinical facts and treatments, depression is an intensely personal experience. For some, it feels like drowning in darkness. For others, it is a hollow numbness. Yet countless individuals who have lived through depression also speak of resilience, growth, and newfound compassion for others.

Recovery is rarely linear—it is often a process of progress and setbacks, of learning to live with vulnerability while building strength. But with treatment, self-care, and support, life after depression can be rich and fulfilling.

Breaking the Stigma

One of the greatest barriers to effective treatment is stigma. Too often, depression is dismissed as laziness, weakness, or a problem to be solved by sheer willpower. These misconceptions silence people, preventing them from seeking help.

Raising awareness, sharing stories, and normalizing conversations about mental health are essential steps toward breaking this stigma. Depression is no more a choice than diabetes or heart disease; it is a medical condition that deserves compassion, understanding, and proper care.

The Future of Depression Care

Research into depression is advancing rapidly. Scientists are exploring the gut-brain connection, inflammation’s role in mood disorders, and the potential of precision medicine to tailor treatments to each person’s biology. Digital tools, such as mental health apps and teletherapy, are expanding access to care worldwide.

While challenges remain, there is hope. The more we learn about depression, the more effective treatments become, and the brighter the future looks for those affected.

Conclusion: Toward Healing and Hope

Depression is a profound illness that touches millions of lives, often silently and invisibly. It is shaped by biology, psychology, and environment, but it does not define the worth of those who experience it. With proper diagnosis and comprehensive treatment—including therapy, medication, lifestyle changes, and social support—recovery is possible.

To understand depression is to understand the depth of human vulnerability, but also the incredible capacity for resilience. By acknowledging its complexity, supporting those who struggle, and breaking down stigma, society can transform depression from a hidden weight into a challenge met with compassion, science, and hope.