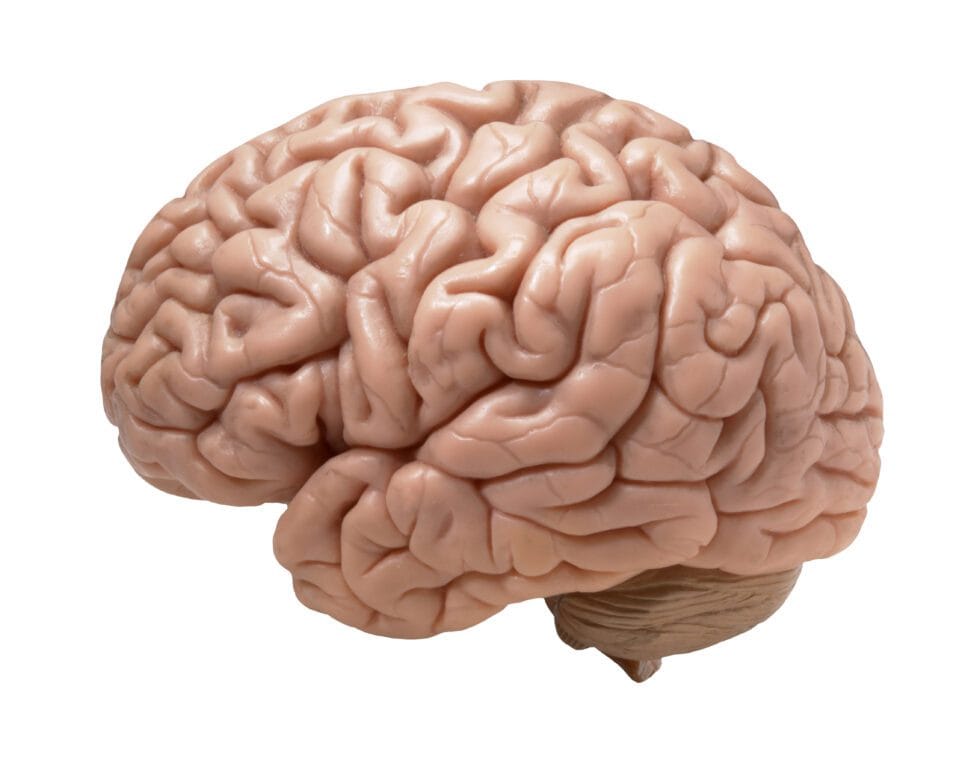

Every laugh, every tear, every moment of joy, fear, rage, or love—each is born from a miracle hidden inside your skull. Though it weighs only about three pounds, the human brain is a labyrinth of over 86 billion neurons, a biological cosmos firing with electric storms of thought, memory, and feeling. Among its most mystifying functions is its ability to create emotions—those intensely personal, sometimes overwhelming experiences that color our lives, drive our decisions, and shape who we are.

But what exactly are emotions? And how does the brain transform the chemical pulses of our bodies and the chaos of the outside world into such vivid, subjective experiences? To understand how the brain processes emotions is to take a journey through some of its most ancient structures, some of its most refined circuits, and some of its most intimate secrets.

Emotion Is Not Just a Feeling—It’s Survival

At first glance, emotion seems purely human. Dogs wag tails, cats purr, but no animal writes poetry about heartbreak or paints masterpieces of grief. Yet from an evolutionary perspective, emotion predates language, civilization, and even reason. It is not a luxury of the soul—it is a survival mechanism.

When early mammals roamed a dangerous world filled with predators, disease, and famine, they needed more than just logic. They needed urgency. Fear helped them avoid predators. Love kept them bonded to kin. Anger gave them strength to defend. Joy encouraged them to seek pleasure and connection. These feelings are not random; they are coded into the body to guide decisions.

Today, humans live in cities and wear wristwatches, but we are still wired for the ancient game of survival. Our emotions help us detect danger, seek pleasure, build social bonds, and navigate an unpredictable world. And the brain is their conductor.

The Limbic System: The Brain’s Emotional Core

Tucked beneath the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer responsible for logic and language, lies the limbic system—a set of interconnected structures deep within the brain. Though far from the only players in emotional processing, these regions serve as an emotional core.

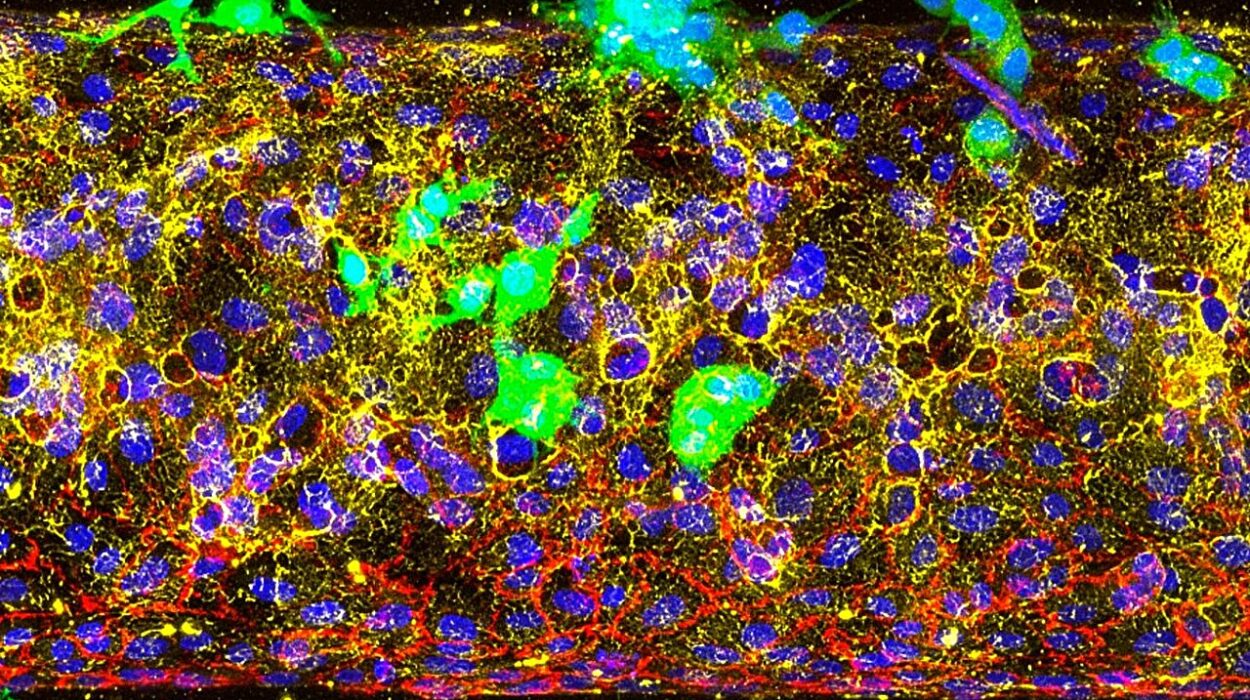

At the center of this system is the amygdala, an almond-shaped cluster of neurons that acts as an emotional sentinel. It scans incoming sensory information for emotional significance, especially threats. If a shadow moves in the dark, the amygdala doesn’t wait to find out if it’s a cat or a criminal—it sets off the alarm bells. It increases heart rate, tightens muscles, and floods the body with stress hormones.

But the amygdala is not just about fear. It’s active in joy, sadness, and even sexual arousal. It tags experiences with emotional weight, helping the brain decide what’s important.

Nearby sits the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure crucial for forming new memories. It links emotions to specific events, giving our lives a narrative shape. Joyful memories of a birthday party, or haunting recollections of trauma, rely on this emotional memory network.

Another key player is the hypothalamus, a small but powerful structure that regulates bodily responses like hunger, thirst, and arousal. It connects the nervous system with the endocrine system, releasing hormones that trigger emotional responses in the body—such as cortisol in stress or oxytocin in bonding.

Together, these structures form a primal network that determines how we react emotionally to the world around us. But that’s just the beginning.

The Cortex: Feeling Meets Thought

While the limbic system provides the raw spark of emotion, the cerebral cortex refines it. This wrinkled outer layer of the brain, especially the prefrontal cortex, allows us to reflect on feelings, regulate them, and understand their meaning.

The prefrontal cortex—located just behind the forehead—is where emotion meets judgment. It’s what keeps you from punching your boss when angry or sobbing uncontrollably in public. This area allows us to assess context, foresee consequences, and regulate impulses. It also plays a key role in emotional decision-making, integrating feelings with logic to guide complex behavior.

Damage to this area, as seen in famous neurological case studies like that of Phineas Gage, can leave people emotionally unstable, impulsive, or indifferent. Without the prefrontal cortex’s input, emotions become chaotic—powerful but misdirected.

The anterior cingulate cortex, meanwhile, serves as a sort of emotional error detector. It monitors conflicts between our thoughts and feelings. If you’re trying to suppress anger during a job interview or fight back tears during a movie, this area helps manage the internal tug-of-war.

The insula, buried deep within the cortex, allows us to feel what’s going on inside our own bodies—a process called interoception. It helps you feel hunger, thirst, pain, or a racing heart, and links these internal sensations to emotional awareness. It’s part of why anxiety often comes with a tight chest, or why embarrassment brings heat to your cheeks.

Together, these cortical areas allow humans not just to feel, but to understand, interpret, and respond to emotions in nuanced and socially appropriate ways.

Chemicals of the Mind: Neurotransmitters and Hormones

While brain regions provide the architecture, neurotransmitters and hormones act as the emotional paint that splashes color onto our experiences. These chemical messengers flow through the brain and body, shaping how we feel at any given moment.

Dopamine, often called the “pleasure chemical,” is involved in reward and motivation. When you eat chocolate, win a game, or fall in love, dopamine floods certain brain areas like the nucleus accumbens, creating a sense of euphoria and reinforcing the behavior.

Serotonin helps regulate mood and social behavior. Low serotonin levels are associated with depression and anxiety. Many antidepressant medications work by increasing serotonin availability in the brain.

Norepinephrine, released during stress, sharpens focus and raises alertness. It prepares the body for action during emotional arousal, often working in concert with adrenaline.

Oxytocin, known as the “love hormone,” fosters bonding and trust. It surges during childbirth, breastfeeding, hugging, and sex. It doesn’t just make us feel good—it makes us feel connected.

Cortisol, often vilified, is the stress hormone. It helps the body mobilize energy in times of threat, but chronic high levels are linked to anxiety, depression, and health problems.

These chemicals interact in intricate and ever-changing ways, turning the brain into a dynamic emotional symphony—one that changes from moment to moment and person to person.

Emotion and the Senses: Feeling Through the Body

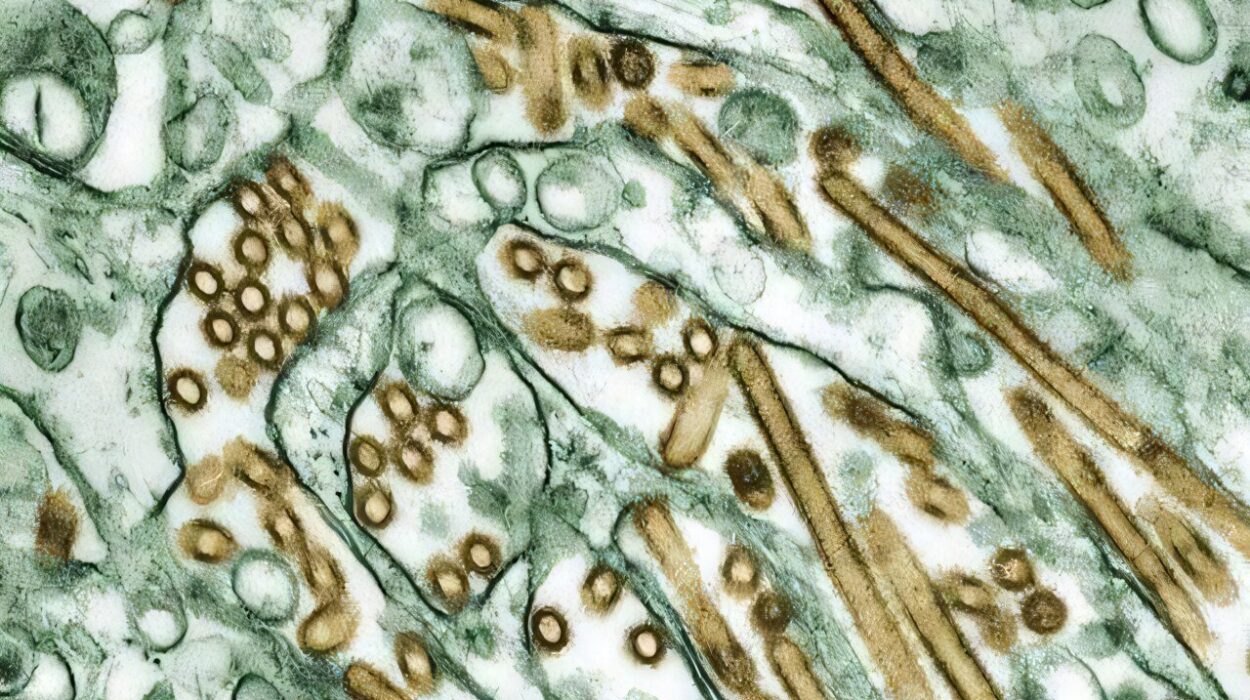

We rarely experience emotions as abstract thoughts. More often, they erupt through our bodies—goosebumps during fear, tears in sadness, a racing heart in love. This is no accident. The brain doesn’t process emotion in isolation—it coordinates with the entire body.

The autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions, plays a major role. The sympathetic branch gears us up for action—raising heart rate, dilating pupils, increasing blood flow to muscles. The parasympathetic branch calms us down—slowing the heart, encouraging digestion, restoring balance.

These bodily changes provide feedback to the brain, creating a loop. According to the James-Lange theory, we don’t cry because we’re sad—we feel sad because we cry. In other words, the brain interprets bodily changes as emotional cues.

This theory, while controversial, is supported by modern research into embodied emotion. Studies show that facial expressions can influence how we feel. For example, forcing a smile—even artificially—can improve mood. Likewise, adopting a “power pose” can increase confidence, likely by affecting hormonal levels.

Our senses, too, are deeply tied to emotion. A song can bring you to tears. A smell can trigger nostalgia. A photograph can flood you with longing. That’s because sensory information is routed through the thalamus, which shares close connections with emotional centers like the amygdala. The result is a brain that doesn’t just see, hear, or smell—it feels.

Emotional Memory: The Past Is Always Present

One of the most haunting aspects of emotion is its tie to memory. A single scent, a song, or a phrase can transport us back in time—sometimes joyfully, sometimes painfully. This isn’t just poetry; it’s neuroscience.

The amygdala and hippocampus work closely to encode emotional memories. The stronger the emotion, the more deeply the memory is imprinted. This is why we remember where we were during major life events—or even traumatic ones—with vivid clarity. Emotional arousal boosts the production of norepinephrine, which enhances memory encoding.

But this can be a double-edged sword. In conditions like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), traumatic memories are so strongly encoded that they become intrusive. Flashbacks, nightmares, and emotional triggers can haunt a person for years. The brain treats the memory as if the danger is still present.

On the other hand, positive emotional memories form the backbone of resilience, helping us recover from hardship. Remembering love, success, or comfort provides psychological scaffolding in times of despair.

Emotion and Decision-Making: The Illusion of Rationality

We like to think of ourselves as logical creatures. But study after study has shown that emotions are not the enemy of reason—they are its foundation. The famous neuroscientist Antonio Damasio studied patients with brain damage that left them emotionally flat. Despite intact intelligence, these individuals made poor life decisions. Without emotion, logic became paralyzed.

Emotions guide us toward choices that feel right, warn us of danger, and anchor our values. The orbitofrontal cortex, part of the prefrontal area, plays a key role here. It assigns emotional value to options and helps weigh consequences. Without it, we are adrift in a sea of meaningless facts.

Even in economics, decision theory has increasingly acknowledged the role of emotion. Behavioral economics, pioneered by researchers like Daniel Kahneman, shows how fear, risk aversion, and hope skew our judgments. Emotions are not flaws in the system—they are the system.

Emotional Intelligence: The Brain’s Social Skillset

Not all intelligence is IQ. In fact, our ability to recognize, understand, and manage emotions—both our own and others’—may be even more vital to success and happiness. This is called emotional intelligence.

It involves several brain networks. Recognizing emotions in others relies on the mirror neuron system, particularly in the inferior frontal gyrus. This system activates both when we perform an action and when we see someone else do it, allowing empathy and imitation.

Managing our own emotions requires robust prefrontal regulation over limbic impulses. Understanding social dynamics depends on the temporal-parietal junction and the medial prefrontal cortex, areas involved in theory of mind—the ability to understand others’ perspectives.

People high in emotional intelligence tend to have healthier relationships, better leadership skills, and more effective coping strategies. And like other skills, it can be trained. Mindfulness, therapy, journaling, and social practice can all refine emotional intelligence by literally rewiring the brain.

The Unconscious Emotional Brain

Not all emotional processing is conscious. In fact, much of it happens beneath our awareness. The subcortical brain responds to emotional stimuli within milliseconds, often faster than we can even name what we’re feeling.

Studies using fMRI have shown that the amygdala can activate in response to fearful faces or threatening stimuli even when the subject is unaware of having seen them. This explains why we can feel uneasy in a room without knowing why, or fall in love before we’ve really spoken to someone.

This unconscious emotional processing shapes first impressions, social judgments, and even prejudice. While this can lead to errors, it also provides the speed and efficiency we need to navigate a complex world.

Culture and Emotion: Shaped by the Brain, Colored by the World

While the brain’s machinery for emotion is universal, how we express and interpret emotions is deeply shaped by culture. In Japan, for example, public displays of sadness may be discouraged, while in Mediterranean cultures, emotional expressiveness is often encouraged.

Cultural norms influence prefrontal regulation of emotional expression. In other words, the brain may feel the same fear or joy everywhere, but what we do with that feeling—how we show it, whether we suppress it, how we interpret others’ emotions—varies across societies.

Even the words we use for emotions shape how we feel. Languages vary in the emotions they name—some have no word for “anxiety,” others distinguish between types of love. This linguistic framing may influence how we encode, recall, and regulate emotional experiences.

Toward a More Compassionate Brain

Understanding how the brain processes emotion doesn’t just satisfy curiosity—it has real-world implications. Disorders like depression, anxiety, PTSD, and borderline personality disorder all involve disruptions in emotional processing. Advances in neuroscience, from neuroimaging to neuromodulation, are helping us develop better treatments.

But beyond pathology, this knowledge invites compassion. When we see that emotional behavior arises from a complex interplay of brain structures, chemicals, experience, and environment, we can judge less and empathize more. Emotions are not flaws—they are features. They are not signs of weakness—they are signatures of life.

The Feeling Brain: A Masterpiece of Nature

At its heart, the brain is not a cold machine. It is an emotional engine, a storytelling organ, a symphony of circuits that lets us love, fear, cry, laugh, and hope. Emotions are not intrusions into our logic—they are the currents beneath it, the colors in the gray matter.

To feel is to be human. To feel deeply is to live fully. And to understand how the brain processes emotion is to glimpse the miracle behind every heartbeat of joy, every storm of anger, every tear of grief, and every whisper of awe.

The next time your heart races or your eyes well up, know that your brain is not betraying you. It is telling you something vital: that you are alive, that you matter, and that even in your most chaotic emotional moments, there is wonder in the wiring.