Every second of your waking life—and even while you dream—your brain is weaving an intricate tapestry of reality. But what if I told you that the world you think you see, hear, touch, and know is not the world itself? That your brain is not a passive mirror reflecting reality, but an active sculptor—shaping, predicting, and even fabricating the world you experience?

You don’t see the world as it is. You see the world as your brain imagines it.

This may sound mystical, but it’s grounded in hard neuroscience. Reality, as you know it, is not simply out there waiting to be observed. It is a construct—a model created by your brain from limited, noisy sensory inputs and an immense ocean of prior knowledge, beliefs, and expectations.

Your eyes are not cameras. Your ears are not microphones. Your skin is not a set of pressure sensors. These organs send raw signals—light, vibration, chemical cues—to the brain, which then interprets them in complex, predictive ways. And sometimes, it gets things spectacularly wrong.

The question is not: “What is reality?” The deeper question is: “How does your brain convince you that its interpretation of reality is real?”

To understand this, we must journey through vision, sound, memory, emotion, prediction, and the brain’s incredible capacity for meaning-making. This is the story of how reality, as you know it, comes to life inside your head.

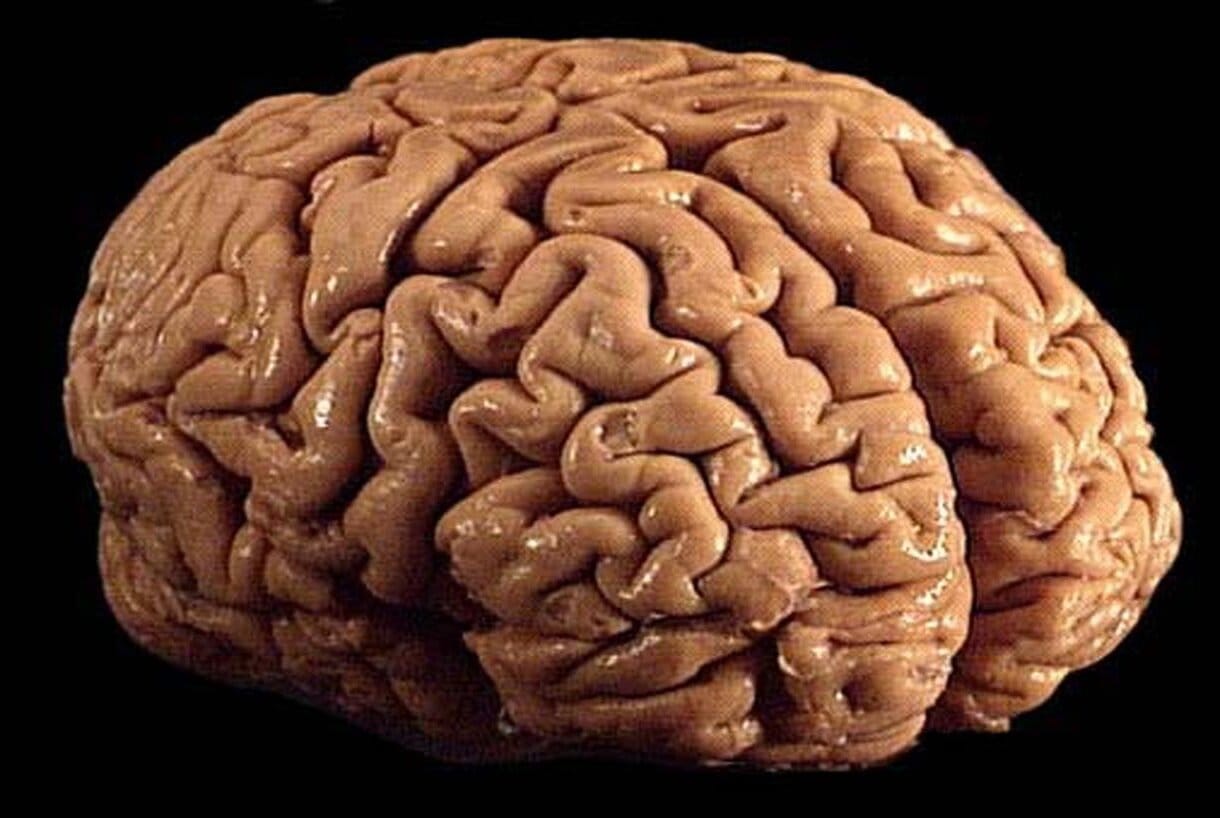

The Illusion of Seeing: Vision as a Construct

You might think that vision begins in the eyes—but it doesn’t end there. Light bounces off objects, enters your pupils, and strikes the retina. But the retina only detects patterns of brightness and color. The real magic happens later.

From the retina, information travels through the optic nerve to the primary visual cortex at the back of your brain. This area, known as V1, is only the beginning of a vast visual processing network. In fact, roughly 30% of your brain is dedicated to processing visual information. But here’s the twist: much of this activity isn’t just reactive—it’s predictive.

Your brain doesn’t wait to “see” what’s out there. It constantly anticipates what it expects to see based on context, memory, and learned experience. That’s why optical illusions work so well—they exploit your brain’s predictions. When your brain guesses wrong, you see something that isn’t there, or fail to see something that is.

Take the phenomenon of “blind spots.” Each of your eyes has a small region on the retina where the optic nerve exits, and there are no photoreceptors—meaning no vision. Yet you never notice this gap. Why? Because your brain fills in the missing data using information from the surrounding area.

This kind of mental “auto-complete” is happening all the time. Visual processing is not a photograph—it’s an inference engine. You don’t passively receive images. You actively interpret them.

And it’s not just illusions. Consider dreams. When you dream, your eyes are closed, yet you see vivid landscapes, faces, movement. Where do these visuals come from? The brain’s own internal model of the world.

That’s the ultimate revelation: seeing is not believing. Believing is seeing.

Sound Without Ears: The Brain’s Sonic Interpreter

What we experience as sound is, at its core, nothing more than changes in air pressure. Yet somehow, these vibrations become melodies, voices, thunder, and laughter.

Your ears are simply the entry point. Sound waves cause tiny movements in the eardrum, which are passed through three small bones in the middle ear to the cochlea in the inner ear. Inside the cochlea, hair cells convert mechanical energy into electrical signals that are sent to the auditory cortex.

But just like vision, hearing is not a direct perception. It’s an interpretation. Your brain determines whether a sound is language, music, or noise. It fills in missing information. In fact, people with hearing loss often report hearing full words even when only fragments are received—because the brain guesses.

Language comprehension especially illustrates how interpretive our hearing is. The phenomenon of the “McGurk effect” shows that what we see can alter what we hear. If you watch a video of someone saying “ga” while the audio says “ba,” your brain might hear “da.” The senses are intertwined. Reality is a negotiation.

Then there’s the role of memory. When you hear a loved one’s voice or a familiar song, the emotional salience isn’t in the sound wave—it’s in the neural associations your brain has formed. You don’t just hear sounds; you hear meaning.

Your brain is not interested in the raw waveform of reality. It wants to know: What does this sound mean for me?

Touch, Taste, and Smell: The Body’s Quiet Narrators

Touch is our most ancient sense, and in many ways, the most intimate. It’s the first sense to develop in the womb, and the last to fade in old age. But again, your brain must interpret what your skin feels.

Pain, temperature, vibration, and pressure all involve different receptors in the skin. But their meaning changes depending on context. A light touch can feel loving or creepy. Warmth can be comforting or scalding. Pain itself is not a direct signal—it’s a brain-generated experience based on both the damage and your emotional state.

Phantom limb syndrome reveals this powerfully. People who have lost a limb often report feeling pain or sensation in the missing part. The brain’s map of the body—the “homunculus”—still contains the limb, and it generates touch even when the body does not support it.

Taste and smell are chemical senses. Molecules in food or air bind to receptors on your tongue and in your nose. But interpretation happens in the brain. The smell of fresh bread might make one person feel comforted, another nauseated. A food you once disliked can become a favorite due to changing neural associations.

The brain doesn’t just detect chemicals—it overlays memory, culture, and emotion on top of them. That’s why a whiff of perfume can bring back a childhood memory with painful clarity. The scent isn’t the memory. The brain turns it into one.

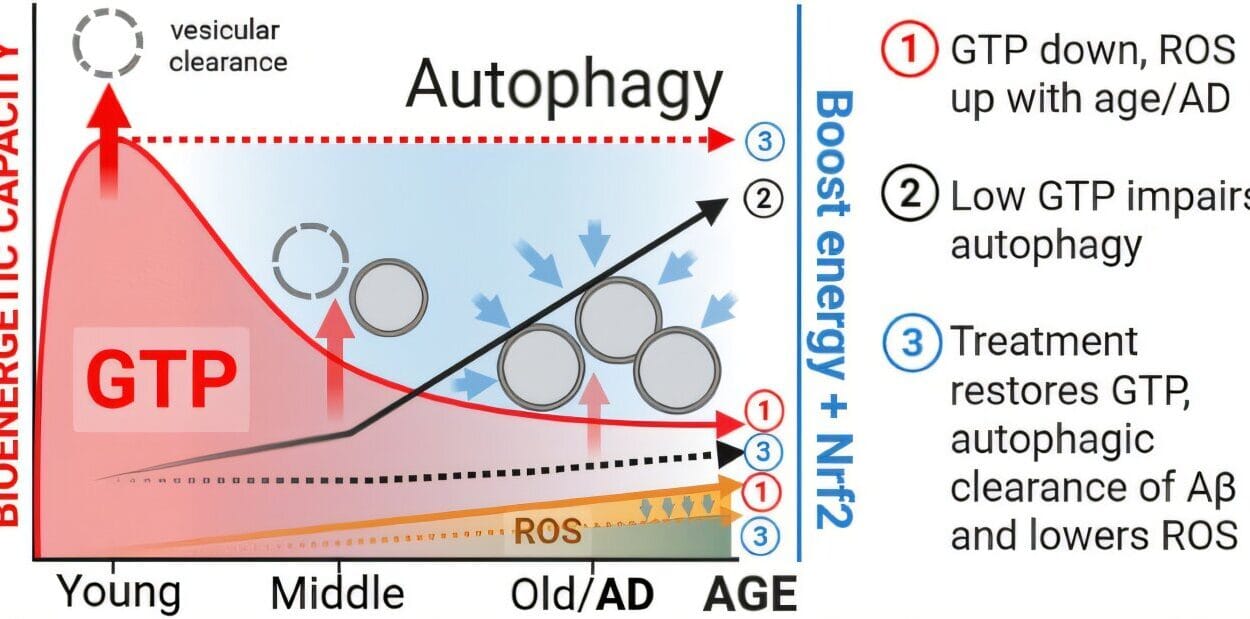

Reality Is Not Real-Time: The Brain’s Predictive Loop

Perhaps the most radical discovery in neuroscience is that your brain is not a real-time processor. In fact, it’s always operating with a delay.

Visual signals can take up to 100 milliseconds to reach the brain. That may seem small, but in a fast-moving world, that lag would be fatal if your brain didn’t compensate. So it cheats. It predicts.

Your brain is constantly forecasting what will happen next. It’s a master of Bayesian inference, updating its models based on new input and prior experience. If reality matches the prediction, all is well. If not, the brain either corrects the prediction—or rewrites the memory.

This is why a fastball appears to slow down just before you swing, or why you duck before a punch lands. The brain is living slightly in the future. What you perceive is the brain’s best guess about what is happening now, based on what it thinks will happen next.

This predictive loop is central to the brain’s architecture. The idea, known as the “predictive coding model,” suggests that perception is essentially controlled hallucination. You don’t see what’s there. You see what your brain expects to be there—and adjusts for surprises.

When those predictions are wildly wrong, you hallucinate. Schizophrenia, for example, may involve prediction errors in the brain’s model of self and world. The patient hears voices not because they are “crazy,” but because their brain misattributes internal speech to an external source.

We are all hallucinating constantly. It’s just that when we agree on our hallucinations, we call it reality.

Memory: The Author of the Past

What about your past? Surely memory is more accurate than sensation?

Unfortunately, memory is even more imaginative.

Your memories are not stored like files in a cabinet. Every time you recall something, you reconstruct it. And each reconstruction is filtered through current beliefs, emotions, and expectations.

This means your memories are not passive records. They’re active stories—stories the brain tells to explain who you are.

Consider the “reconsolidation” process. When you retrieve a memory, it becomes labile—modifiable—and is then re-stored. That means every act of remembering is also an act of editing. We don’t just remember the past. We recreate it in the present.

This is why eyewitness testimony is often unreliable. It’s why siblings remember the same childhood event differently. The brain isn’t lying maliciously—it’s just doing what it always does: telling the most coherent story it can, even if it has to invent parts.

Trauma plays a particular role here. In traumatic memories, the brain may amplify emotional elements while suppressing factual ones. Time can become distorted. Sensory details may become hyper-vivid—or disappear altogether. The result is not a false memory, but a distorted reality.

We live not just in the present, but in a remembered world—one our brain is constantly rewriting.

Emotion: The Sculptor of Meaning

No perception is purely neutral. Every sensation, every memory, every thought is tinged with emotional significance. The brain doesn’t just process what’s happening—it assigns value. It answers the question: “Does this matter?”

Emotions are not merely reactions. They are judgments, integrating bodily signals, context, and personal history. The amygdala, often called the “fear center,” is central to this process—but it works in concert with the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and insula to create a map of emotional salience.

Even something as simple as seeing a spider or hearing a loud bang triggers not just visual or auditory processing, but emotional evaluation. Your body tenses, your heart races. The emotion becomes part of the perception. You don’t just see a spider. You feel “spiderness.”

This emotional coloring extends to abstract thoughts. A belief that contradicts your worldview may be felt as physically unpleasant. A moral violation might disgust you as much as spoiled food.

In this way, emotion sculpts reality. What you care about determines what you notice, what you remember, and what you believe. The world you live in is not the one your senses detect—it’s the one your emotions select.

The Self: An Ongoing Invention

If reality is an illusion, then what about the self?

The sense of being “you”—a stable, continuous identity—feels so natural that we rarely question it. But neuroscience shows that the self is a construct, built from multiple brain systems integrating over time.

There is no single “self center” in the brain. The default mode network, active when your mind wanders or reflects inward, plays a key role. So do regions responsible for memory, emotion, and body awareness.

This is why conditions like dissociative identity disorder or depersonalization can occur. When the integration breaks down, the self can fragment—or feel unreal.

Even your sense of body ownership is malleable. The famous rubber hand illusion shows that if a rubber hand is stroked in synchrony with your hidden real hand, you begin to feel the rubber hand is yours. The brain rewires its body map on the fly.

So who are you? You are a story—told by your brain to make sense of your memories, goals, sensations, and social roles. And like all stories, it changes with time.

Conclusion: Living in the Brain’s Theater

You do not live in the world. You live in a story your brain tells about the world.

This story is not false. It’s functional. It allows you to navigate, connect, survive. But it’s also incomplete, biased, and constructed. Your reality is a brain-made model, shaped by evolution to emphasize survival, not truth.

Understanding this can be disorienting. But it can also be liberating.

It means you are not condemned to one perception. You can learn to notice your brain’s patterns. You can expand your model. Meditation, therapy, art, and science all help you see not just the world—but how you see the world.

Neuroscience does not strip life of meaning. It reveals how meaning is made.

And in that realization lies both humility and wonder.

Your brain is a 3-pound organ of flesh and electricity. And yet from it arises color, memory, music, love, identity, and the idea of a universe.

Is that not the greatest magic trick of all?