In the grey light of a 1991 autumn morning, archaeologists uncovered a mystery on the foreshore of the Thames River in London. The discovery was quiet and unassuming: human bones, worn smooth by time, tucked carefully within sheets of bark and laid gently on a bed of reeds. The body was not buried in a grave, but instead left exposed—resting on the muddy riverbank, where the rising tide could lap at her remains and the living could witness her fate. This was no ordinary burial.

For over two decades, the story of this woman remained locked in museum storage—an unresolved puzzle from England’s dark past. But thanks to a recent forensic and archaeological investigation led by Dr. Madeline Mant and her colleagues, this woman—catalogued as UPT90 SK 1278—has begun to speak again, her bones revealing a haunting story of violence, justice, and the shifting tides of early medieval law.

A Woman from the Edge of History

The remains, now housed at the Museum of London, have been dated to between 680 and 810 AD—an era of profound transition in Anglo-Saxon England. This was a time when Christianity was solidifying its grip, kingdoms were coalescing, and law codes were evolving in complexity and brutality. The woman had been between 28 and 40 years old when she died. Isotope analysis tells us she was local—likely born and raised in or around London, eating a diet primarily of terrestrial origin. Yet, around the age of five, her dietary record changed. Her bones show a sharp rise in nitrogen isotopes—something that can indicate either a temporary increase in meat consumption or a desperate period of starvation.

This seemingly subtle shift is crucial. It suggests her early life was not one of privilege. Perhaps her family faced a famine, a personal crisis, or fell into poverty. Malnutrition or hardship early in life can affect health and status permanently, and in early medieval England, such changes could spell a lifetime of marginalization.

But it is the story of her death—and what came after—that truly sets her apart in the archaeological record.

The Violence That Preceded Death

What happened to UPT90 SK 1278 was nothing short of brutal. Her skeleton bears the evidence of not one, but two violent assaults. The first occurred approximately two weeks before her death, inflicting hairline fractures to both scapulae (shoulder blades). Today, these types of injuries are most often seen in car accident victims—high-force trauma typically caused by collisions or being struck from behind.

In a ninth-century context, such injuries almost certainly point to deliberate violence. Perhaps she had been flogged, thrown to the ground, or struck with a heavy object. The second assault was even more savage. Her ribs, spine, and skull were injured in a pattern that strongly resembles what forensic scientists call a “torture beating.” Kicks, punches, or beatings with blunt objects caused a cluster of fractures on her torso and head. The final act was precise and fatal—a blow to the left side of her skull that ended her life.

Her body tells a story of sustained and intentional violence. But it also speaks of a legal system in transformation, a society grappling with how to enforce authority and who had the power to determine life or death.

Law, Punishment, and Public Spectacle

Dr. Mant and her team suggest that UPT90 SK 1278 was executed under the legal codes of her time. Though Æthelberht of Kent (r. c. 589–616) had codified one of the earliest law codes in Anglo-Saxon England without specific references to corporal punishment, later rulers took a different view. Wihtred of Kent (r. 690–725), for instance, instituted punishments that included beatings for those unable to pay fines. By the time of King Alfred (r. 871–899), the law had grown even harsher—expanding the list of capital crimes to include theft, treason, witchcraft, and sorcery. Execution could come through stoning, drowning, or, as in this case, blunt force trauma.

What remains elusive is the precise crime for which this woman was condemned. Her punishment was fatal, her injuries systematic. Was she accused of theft? Heresy? Sorcery? We may never know. But her execution speaks volumes about a justice system where the law’s force could fall most brutally on those least able to defend themselves.

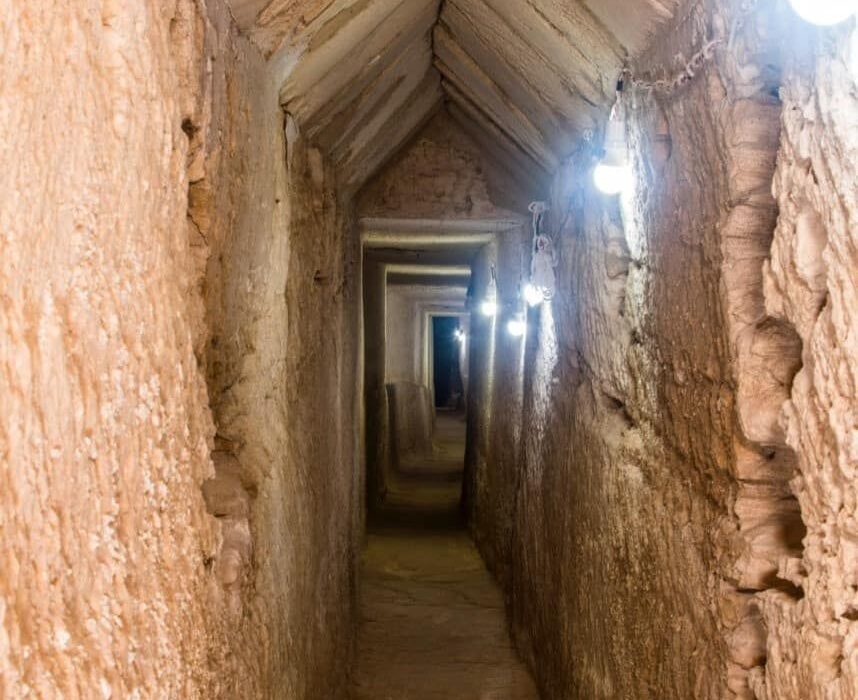

Equally significant is the nature of her burial—or rather, her exposure. Instead of being interred in a grave, she was laid out between two sheets of bark, with moss pads on her face, pelvis, and knees. She rested on a mat of reeds in full view of the river, placed deliberately on the foreshore where the Thames would rise and fall around her. This was not an accident or a convenience. It was a message.

The Foreshore: A Stage for the Dead

In early medieval belief systems, space carried meaning. To be buried in a churchyard was a privilege. To be buried in a pit, forgotten and anonymous, was more common. But to be displayed in a liminal space—a threshold between land and water, life and death—was different altogether.

The Thames foreshore has long been considered a “symbolic boundary.” In both life and death, bodies placed in these in-between spaces often carried connotations of deviance or criminality. As Dr. Mant notes, “criminal behavior is perceived as deviant; thus, a non-normative burial location could be a contextual clue as to how the individual was perceived during their life.”

The bark wrapping may have symbolized a kind of makeshift coffin, but it was also a visual frame—emphasizing her body as an object of display. Moss pads may have served a ritual purpose, but they also added to the theatricality of her positioning. At high tide, her body would have been visible to passing boats and riverside communities. Perhaps she was meant as a warning, a deterrent—a human signpost marking the boundaries of law and morality.

A Rare Glimpse into Female Execution

Execution in early medieval England was relatively rare. Archaeological surveys of execution cemeteries indicate an average of one execution per decade. What’s more, the vast majority of known victims were men. Male-to-female ratios in such cemeteries are often as high as 4.5 to 1. The remains of UPT90 SK 1278 are thus doubly rare: not only was she executed, but her body was subjected to a spectacle typically reserved for high-status political statements or deeply feared social transgressions.

Her gender makes her case even more striking. In a society where women were often excluded from legal agency, to be executed as a woman suggests either an extraordinary crime—or an extraordinary breakdown in the protections typically afforded to women, particularly those of reproductive or domestic roles.

This rare example offers an exceptional window into how law and gender intersected in early medieval England. She was not buried as a martyr, saint, or noblewoman. She was not cast aside as refuse. Instead, she was staged—her death made public, her body made meaningful.

The Silence That Followed

After her death, the woman who was once UPT90 SK 1278 was forgotten. No written record of her crime survives. No local legend, no preserved name. Her bones were moved to a museum shelf, uncatalogued, for over twenty years.

But now, through forensic science and archaeological interpretation, she speaks again.

Her story tells us about violence—but also about power, ritual, and remembrance. It speaks of a moment when the law was becoming something physical, something inscribed not only on parchment but on bodies. Her injuries were not only personal—they were legal texts in flesh and bone.

She is both an individual and a symbol, a person and a public performance.

Conclusion: Memory from the Mud

The woman on the Thames foreshore did not vanish into obscurity. She was placed there deliberately—to be seen, to be judged, to be remembered. But memory is a strange thing. Though her contemporaries may have watched her body as the tide rose, they left no record of her name or her story.

It has taken over a thousand years and the tools of modern science to reconstruct even the faintest whisper of her life. Yet in that reconstruction, we find something enduring. We see not only a woman subjected to brutal justice, but also a human being whose death was part of a larger cultural script—one that linked law, space, body, and power in ways both alien and strangely familiar.

Her remains now rest in a controlled museum environment, but her story has re-entered the public imagination. In this, perhaps, there is a quiet justice: that her life, her suffering, and her forced performance on the edge of the river are not forgotten.

The Thames still flows past that ancient foreshore, washing over the boundary between past and present. And now, in that flow, the voice of one woman—beaten, executed, displayed—rises again, asking us to witness her fate and learn from what her bones have finally told.

Reference: Madeleine Mant et al, Evidence for punishment and execution on the foreshore: a unique early medieval burial (680–810 AD) from London, World Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00438243.2025.2488739