In the rolling hills of Děčín in northern Bohemia, an ancient forest once thrummed with life—lush canopies, chirping proto-birds, and buzzing insects weaving intricate dances in the humid air. Time turned that verdant scene into stone, preserving its drama and deception for tens of millions of years. Now, paleontologists at Charles University have cracked open a 33-million-year-old secret: a fossilized hoverfly so uncannily like a wasp that it seems to have borrowed not just its outfit, but its very identity.

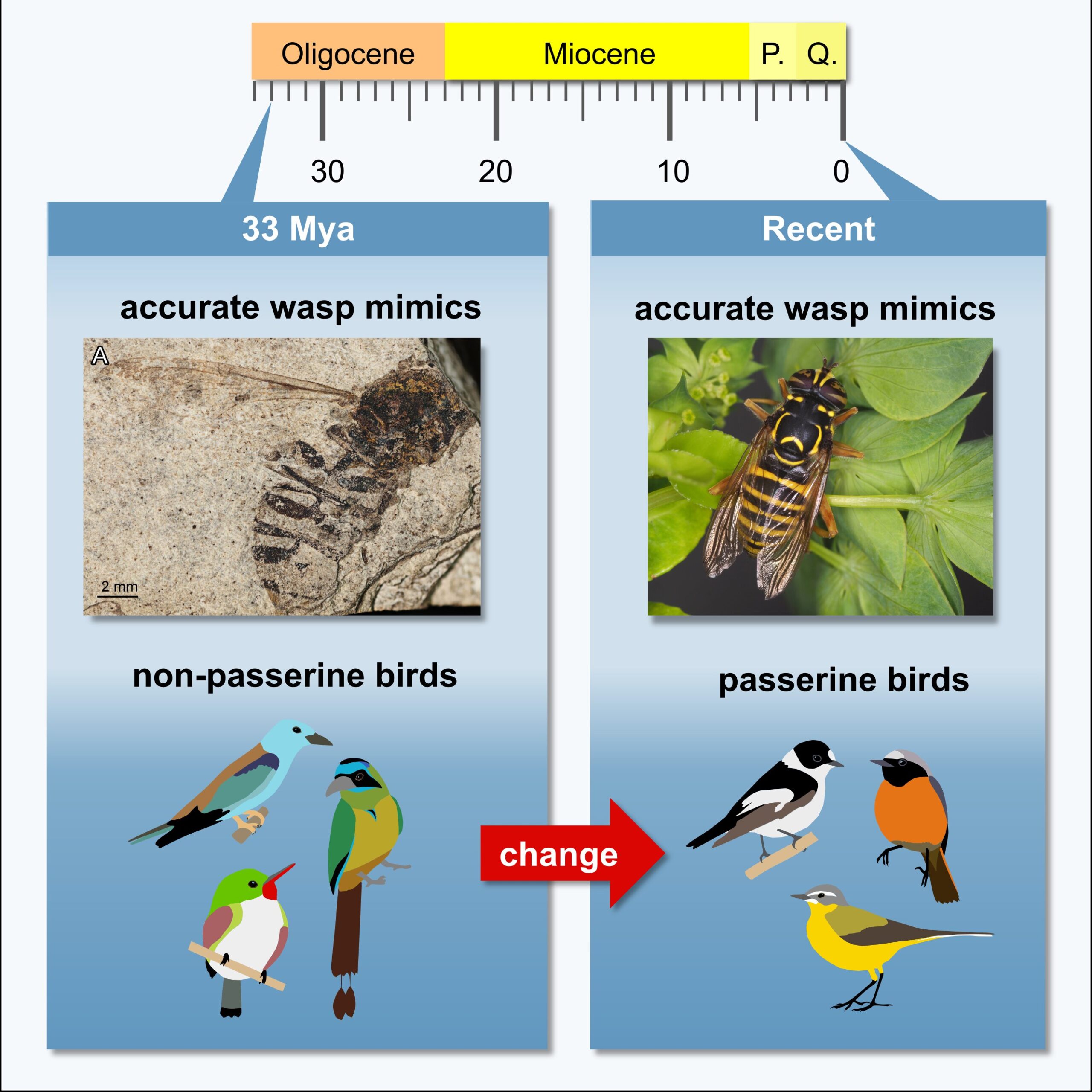

The fossil, Spilomyia kvaceki, is the oldest known example of accurate Batesian mimicry—a defensive evolutionary trick where harmless species imitate dangerous ones to fool predators. Impeccably preserved, this specimen stuns not only in its beauty but in what it reveals: mimicry didn’t evolve in the shadow of modern insect-eating birds. It predates them.

A Master of Disguise, Long Before Passerines

Hoverflies, or syrphids, are evolutionary con artists. Modern species flaunt bold stripes, triangular heads, and an unnervingly convincing wasp-like buzz, all while remaining harmless nectar-feeders. Until now, however, fossil evidence for this mimicry had been weak—hazy impressions, vague color patterns, or poorly preserved anatomy.

Spilomyia kvaceki changes that. Excavated from the renowned Early Oligocene site of Děčín-Bechlejovice in the Czech Republic, the fossil bears stunning detail in its wings, body proportions, and, crucially, its coloration pattern. Under a microscope, the banding is unmistakable: a wasp’s armor, painted onto a fly’s body.

“This isn’t just a vague resemblance,” says Klára Daňková, lead researcher on the study published in Current Biology. “The fly doesn’t just look a bit like a wasp—it looks exactly like one. This degree of precision suggests strong and specific evolutionary pressure even at this early date.”

But who, or what, was applying that pressure?

The Predator’s Gaze in Deep Time

In today’s ecosystems, mimicry is largely shaped by birds—particularly passerines, or perching birds, the most diverse and dominant avian group in Europe. They are expert insect hunters with sharp vision and finely tuned instincts. Hoverflies have evolved to avoid their beaks by looking like something unappetizing: stinging wasps.

But 33 million years ago, Europe had no passerines. They had yet to diversify into the insect-snagging virtuosos we know today. Instead, it was birds from the Coraciimorphae (including rollers and kingfishers) and Apodiformes (the group containing swifts) that ruled the skies. These birds, now considered peripheral in insect predation, were then likely major players in shaping the evolutionary arms race between insects and their predators.

This is what makes the discovery of S. kvaceki so significant. It forces a rethink of mimicry’s timeline and the ecological dynamics that drove it. “We often assume that mimicry evolved in response to the world as it is now,” Daňková explains. “But this fossil reminds us that the world was once very different—and evolution responded to that world, not ours.”

A Community of Impostors and Originals

The fossil site yielded more than just a master of mimicry. It also contained the likely object of imitation: extinct wasps of the genus Palaeovespa, a now-extinct group closely related to modern social wasps. Their presence in the same sedimentary layers as Spilomyia kvaceki suggests an ancient cohabitation—and a visual template for mimicry.

This proximity matters. Batesian mimicry requires not just a mimic and a predator, but a model—an organism dangerous enough to make the lie believable. For mimicry to evolve, the predator must learn to avoid the model, and then mistake the mimic for the real thing. The presence of Palaeovespa supports this triangle of interaction.

What’s more, the abundance of both mimic and model species in the same strata hints at an ecosystem rich in visual cues, where sight was a primary tool for survival. It implies that, even 33 million years ago, visual deception had become a matter of life and death.

Time-Traveling Through Mimicry

To understand the full significance of this fossil, we need to step back and appreciate the broader phenomenon it represents. Batesian mimicry is named after 19th-century English naturalist Henry Walter Bates, who observed it in butterflies of the Amazon. He noticed that harmless butterflies often bore a strong resemblance to toxic species—a trick to dissuade predators.

But mimicry isn’t exclusive to butterflies. Across the tree of life, animals pretend to be something they’re not. Non-venomous snakes mimic venomous ones. Harmless octopuses morph into lionfish or sea snakes. Even some birds copy the alarm calls of others to frighten competitors.

Hoverflies are one of the most widespread and successful groups of mimics, with some 6,000 species found worldwide. Their success lies not just in their performance—hovering like drones, buzzing like wasps—but in their costume design. Many wear warning colors (aposematism), especially black and yellow banding, common in stinging hymenopterans. This fossil confirms that the tradition of evolutionary cosplay has much deeper roots than anyone suspected.

Not Just a Fly—But a Signal in Stone

The preservation of this fossil is exceptional. Oligocene sediments at Děčín-Bechlejovice act like nature’s photo lab, fixing ancient organisms in fine-grained silt that captured not just form, but even pigmentation patterns. Scientists used ultraviolet light and high-resolution microscopy to tease out details invisible to the naked eye. What emerged was not just a fossil—but a message.

The message is complex and multilayered. It tells us that mimicry evolved earlier than previously thought. It tells us that visual predators were a potent evolutionary force even before the rise of passerines. And it tells us that the insect world of the Oligocene was far from primitive. It was already engaging in psychological warfare, using color, form, and behavior to manipulate perception and survive.

The Names Behind the Discovery

Naming a new species is a rare privilege and a solemn responsibility. Spilomyia kvaceki honors Zlatko Kvaček, an eminent Czech paleobotanist known for his work in reconstructing ancient European ecosystems. His decades of research laid the groundwork for understanding the floristic and faunal context in which this fly once lived. In many ways, the fossil is a tribute not just to ancient evolution but to modern scholarship—a bridge across eras built from curiosity and stone.

Implications for Evolutionary Biology

This discovery reverberates far beyond entomology. It challenges long-held assumptions about the timing of mimicry, the ecology of ancient Europe, and the visual capabilities of extinct predators. Most theories about mimicry assume it evolved relatively recently, shaped by predator-prey interactions familiar to us today. But this fly tells us that deception, like life, is old.

It also supports the idea that mimicry can evolve in vastly different ecological contexts—as long as the right pressures exist. “This shows that complex mimicry doesn’t require modern conditions to arise,” Daňková emphasizes. “It only requires that deception offers a survival advantage—and that the audience is watching.”

This has implications for evolutionary modeling, especially in understanding convergent evolution—where different species independently evolve similar traits. The mimicry of S. kvaceki likely evolved under different pressures than modern hoverflies, yet the outcome is strikingly similar. Nature, it seems, finds a way to return to effective designs.

A Living Legacy

Though Spilomyia kvaceki is long extinct, its lineage lives on. Modern Spilomyia species still flit through forests and gardens, performing their wasp impersonations with uncanny grace. We rarely give them a second glance—until we realize we’ve been fooled. And that, perhaps, is the ultimate testament to evolution’s artistry: that even today, millions of years later, we are still falling for the same trick.

So the next time you see what looks like a wasp hovering near flowers, pause. Look closer. You might just be witnessing one of nature’s oldest and most successful lies—a lie written not just in stripes, but in stone.

Reference: Klára Daňková et al, Highly accurate Batesian mimicry of wasps dates back to the Early Oligocene and was driven by non-passerine birds, Current Biology (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.02.069