From a distance, NGC 4486B looks calm, almost unremarkable. It is a compact elliptical galaxy tucked into the crowded heart of the Virgo Cluster, an old system that astronomers have long considered settled and serene. Its stars are tightly packed within an effective radius of about 620 light years. Its total stellar mass is estimated at roughly 6 billion times the mass of the Sun. Nothing about its smooth outline suggests turmoil.

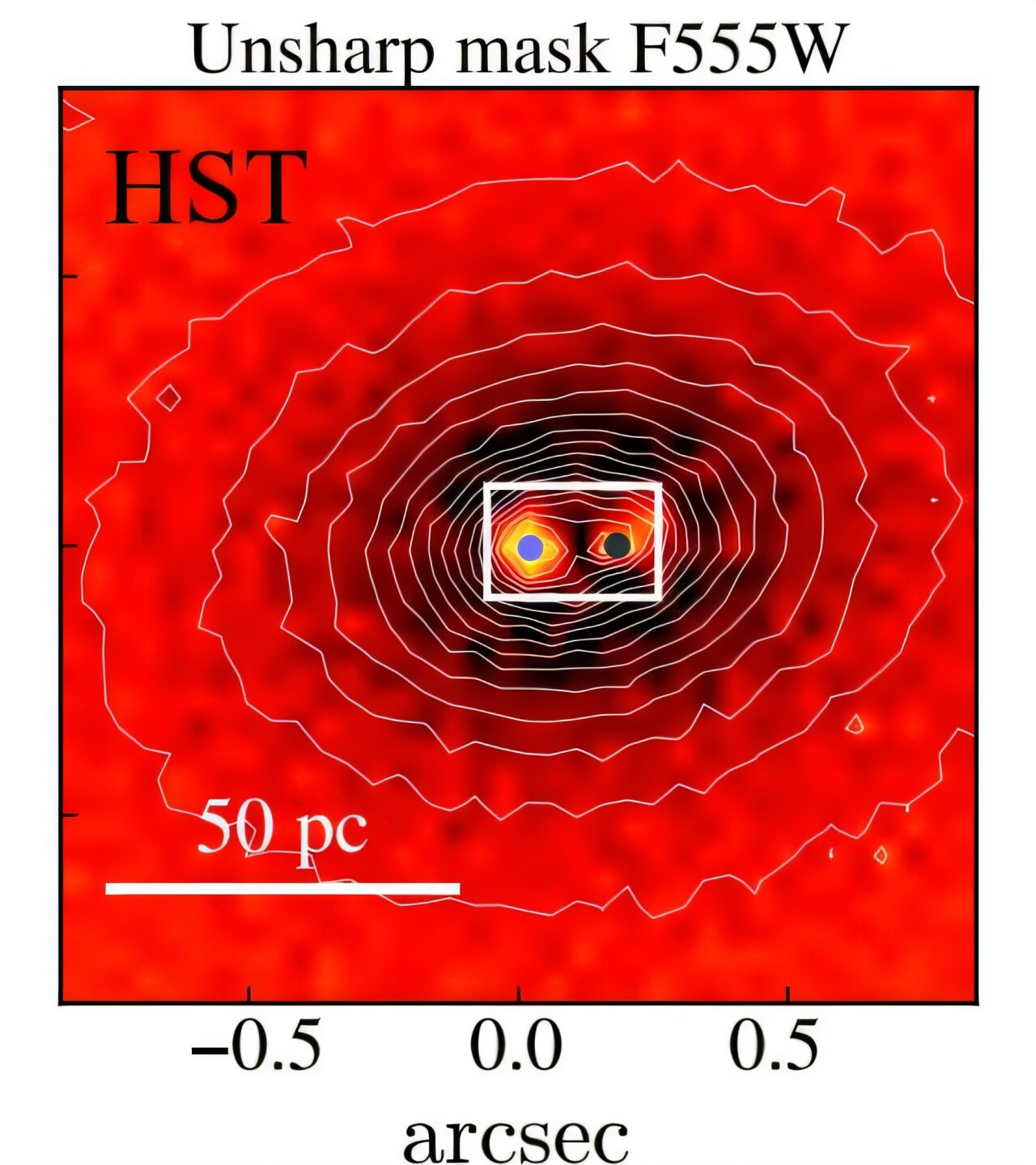

Yet hidden at its center is a mystery that has lingered for years, a strange duplication where there should be unity. Instead of a single bright core, NGC 4486B contains two. The two peaks of light sit about 39 light years apart, close enough to be bound together, distant enough to raise troubling questions. Why would a galaxy grow two centers?

For a long time, the answer remained elusive. Now, with the piercing infrared vision of the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers believe they are finally seeing the story written into the galaxy’s core.

When One Nucleus Becomes Two

The double nucleus of NGC 4486B was not discovered by chance. Earlier observations with the Hubble Space Telescope had already revealed that this galaxy shares an unusual feature with the Andromeda galaxy, another system known to host a split nucleus. In both cases, the duplication appears not as two separate galaxies colliding, but as two brightness peaks embedded within a single gravitational structure.

The origin of such a structure has never been obvious. One leading idea proposed that the double nucleus is an illusion created by stars moving in an eccentric pattern around a central supermassive black hole. In this picture, stars do not orbit in neat circles. Instead, they trace elongated paths that align in a particular way, piling up light in two regions and creating the appearance of two centers.

But until recently, this idea remained a hypothesis, lacking the detailed measurements needed to confirm it.

Webb Turns Its Gaze Inward

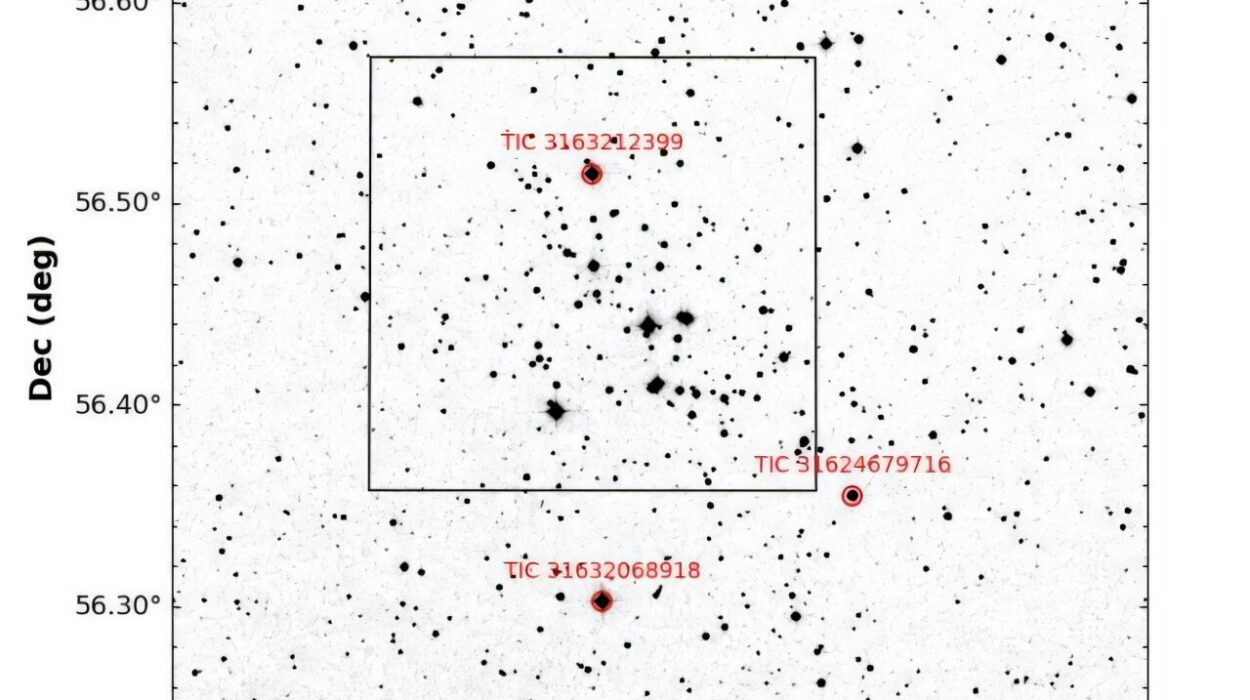

To unravel the mystery, an international team of astronomers led by Behzad Tahmasebzadeh of the University of Michigan turned to the James Webb Space Telescope and its Near-Infrared Spectrograph, known as NIRSpec. Their goal was precise and ambitious: to disentangle the origin of the double nucleus by examining both the light distribution and the motion of stars in unprecedented detail.

Their observations were complemented by earlier Hubble data, allowing the team to connect sharp new measurements with a longer observational history. As they analyzed the data, a clearer picture began to emerge.

“In this work, we investigate the photometric and kinematic signatures of the double nucleus in NGC 4486B,” the researchers wrote in the paper.

What they found suggested that the galaxy’s calm appearance hides a dramatic past.

A Black Hole Out of Place

One of the most striking results from the Webb observations was the discovery that the galaxy’s core is unusually flat, extending out to a radius of about 65.2 light years. Even more surprising was the location of the supermassive black hole itself.

Rather than sitting squarely at the center of the galaxy, the black hole was identified roughly 19.5 light years away from the middle. It also appears to have a small but significant velocity offset of about 16 kilometers per second relative to stars on the opposite side of the galaxy.

This offset is not random noise. It is a clue. It suggests motion, imbalance, and a system still settling after a disturbance.

In the language of galaxies, this is a whisper of violence.

The Shape of an Eccentric Disk

Taken together, the observations point strongly toward a specific explanation. The double nucleus of NGC 4486B appears to be the result of an eccentric nuclear disk, often shortened to END, similar to the one observed in the Andromeda galaxy.

In this scenario, stars orbit the supermassive black hole in elongated paths that are apsidally aligned, meaning their closest and farthest points line up. This alignment causes stars to linger longer at certain locations, creating peaks in brightness that look like separate nuclei.

The team notes that this interpretation fits well with what has been seen in simulations. Previous studies have shown that the surface brightness patterns and stellar motions predicted for such eccentric disks closely resemble what is observed in NGC 4486B. In particular, the fact that the fainter brightness peak coincides with a peak in velocity dispersion matches predictions for nearly edge-on eccentric disks.

The galaxy’s strange heart, it seems, is not split after all. It is stretched.

A Kick From the Darkness

But what could transform a calm, circular stellar disk into an eccentric, lopsided structure?

The answer lies in one of the most extreme events in the universe: the merger of supermassive black holes.

According to the researchers, a gravitational wave recoil kick can naturally reshape a stellar disk bound to a black hole. When two supermassive black holes merge, they release gravitational waves asymmetrically. The imbalance can send the newly formed black hole recoiling through space at tremendous speed.

Based on the observed properties of NGC 4486B’s nucleus and the estimated mass of its black hole, the team calculated that the black hole likely experienced a recoil kick of about 340 kilometers per second. Such a kick would be powerful enough to displace the black hole from the center and distort the surrounding stellar orbits into an eccentric configuration.

Yet this displacement would not last forever. The researchers predict that with a kick of this magnitude, the black hole should settle back to the galaxy’s center within roughly 30 million years.

In cosmic terms, that is a blink of an eye.

An Old Galaxy With a Recent Secret

What makes this discovery especially compelling is the nature of NGC 4486B itself. This is not a young, chaotic galaxy still forming its structure. It is described as old and relaxed, sitting near the center of the Virgo Cluster where interactions have long since slowed.

And yet, the evidence suggests that its supermassive black hole merger happened relatively recently.

“Thus, although NGC 4486B is an old, relaxed galaxy near the Virgo cluster center, its SMBH appears to have merged only recently, making its nucleus a rare nearby laboratory for studying post-merger SMBH dynamics,” the authors of the paper concluded.

This contrast between appearance and history is what gives the galaxy its quiet drama. On the outside, it looks settled. On the inside, it still bears the scars of a violent encounter.

Why This Galaxy Matters

NGC 4486B is more than an oddity. It is a nearby window into processes that are usually hidden at immense distances and timescales. Supermassive black hole mergers are fundamental events in the evolution of galaxies, yet their immediate aftermath is difficult to observe. The signs fade quickly, and the distances involved often blur the details.

Here, astronomers have found a system close enough and clear enough to study in detail, a natural laboratory where theory, simulation, and observation converge. The offset black hole, the eccentric stellar disk, and the double nucleus together form a coherent narrative of what happens after a black hole merger.

This research matters because it connects the abstract world of gravitational waves and simulations to tangible structures we can see and measure. It shows that even galaxies we consider old and stable may carry recent histories of upheaval, written subtly into the motions of their stars.

Most of all, it reminds us that galaxies are not static monuments. They are living systems with memories. In the case of NGC 4486B, the memory takes the form of a split heart, slowly healing as gravity guides everything back toward balance.

More information: Behzad Tahmasebzadeh et al, JWST Observations of the Double Nucleus in NGC 4486B: Possible Evidence for a Recent Binary SMBH Merger and Recoil, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2512.14695