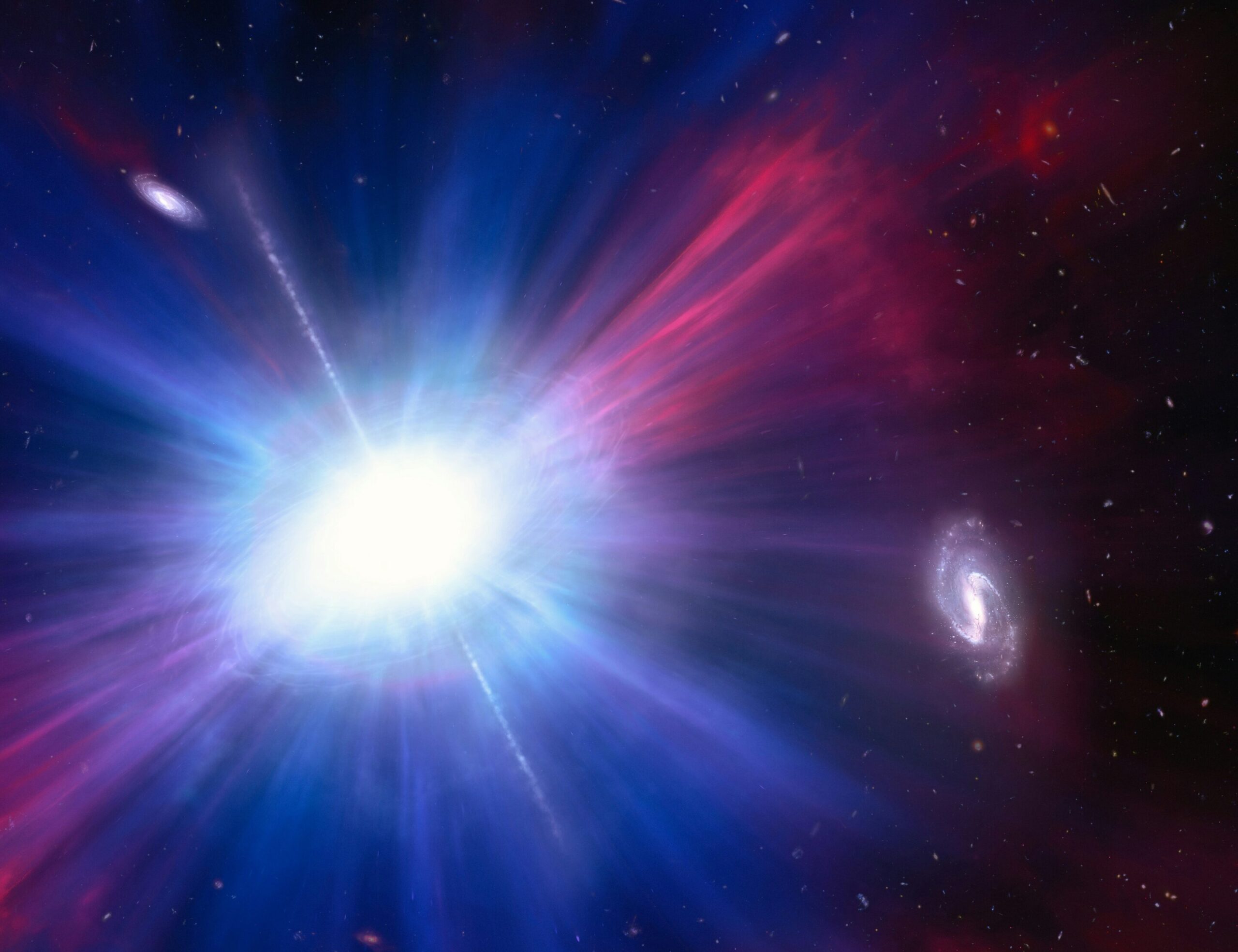

On March 14, 2025, something ancient screamed across the cosmos and briefly touched our modern instruments. It was a burst of high-energy radiation, intense and fleeting, arriving from a time when the universe itself was still young. At that moment, no one yet knew they were witnessing the death of a massive star that had lived and died more than 13 billion years ago, when the universe was only about 730 million years old.

That signal, detected by the space-based multi-band astronomical Variable Objects Monitor known as SVOM, marked the beginning of an extraordinary scientific pursuit. Astronomers realized they were seeing a long-duration gamma-ray burst, or GRB, a phenomenon already known to be associated with the violent collapse of massive stars. This particular burst was labeled GRB 250314A, but its true significance would only emerge later, after patient observation and careful analysis.

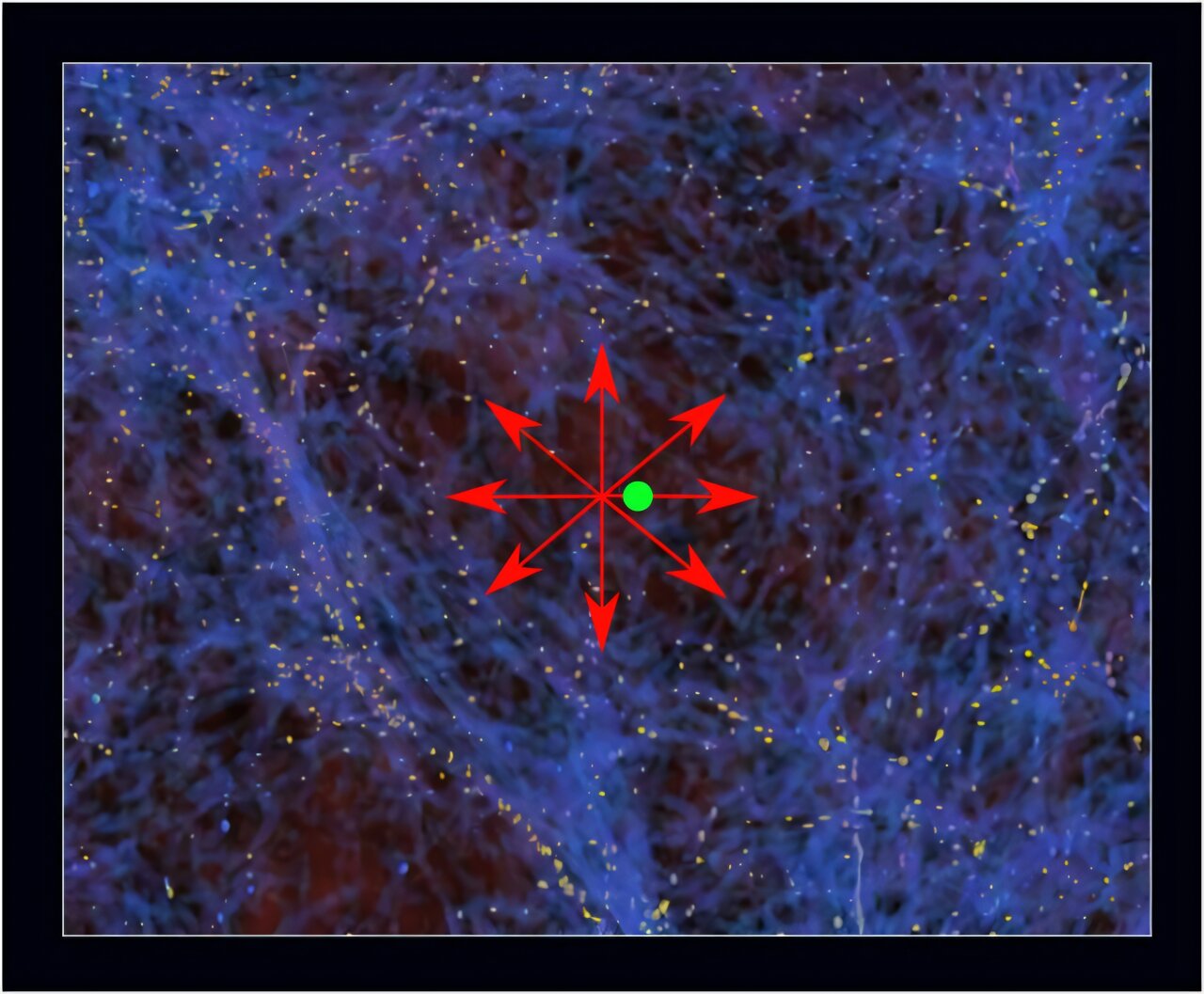

What followed was not just the detection of a distant explosion, but a rare and intimate glimpse into the final moments of a star that lived during the era of reionization, a formative chapter in cosmic history when the first stars and galaxies were beginning to shape the universe.

Following the Trail of a Cosmic Death

The initial gamma-ray burst was only the first clue. Gamma-ray bursts are powerful, but they fade quickly, leaving astronomers racing against time. To understand what caused GRB 250314A, researchers needed to know how far away it was. Follow-up observations with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope confirmed that the source lay at an extreme distance, corresponding to a redshift of about 7.3.

This placed the event deep in the early universe, far beyond the reach of most supernova studies. Almost every supernova ever observed has occurred relatively close to Earth in cosmic terms. Only a handful have been seen at truly vast distances, and none had been directly probed in such detail during this early epoch.

At this point, the story could have ended as another mysterious flash from the distant universe. But the team suspected there was more light to be found, light that would arrive later, slower, and fainter. They believed that behind the gamma-ray burst, a supernova was quietly unfolding.

Waiting for the Afterglow to Fade

Supernovae do not reveal themselves immediately after a gamma-ray burst, especially at such distances. Their light must first compete with the glare of the burst itself and the faint glow of the host galaxy. Time, patience, and the right instrument were essential.

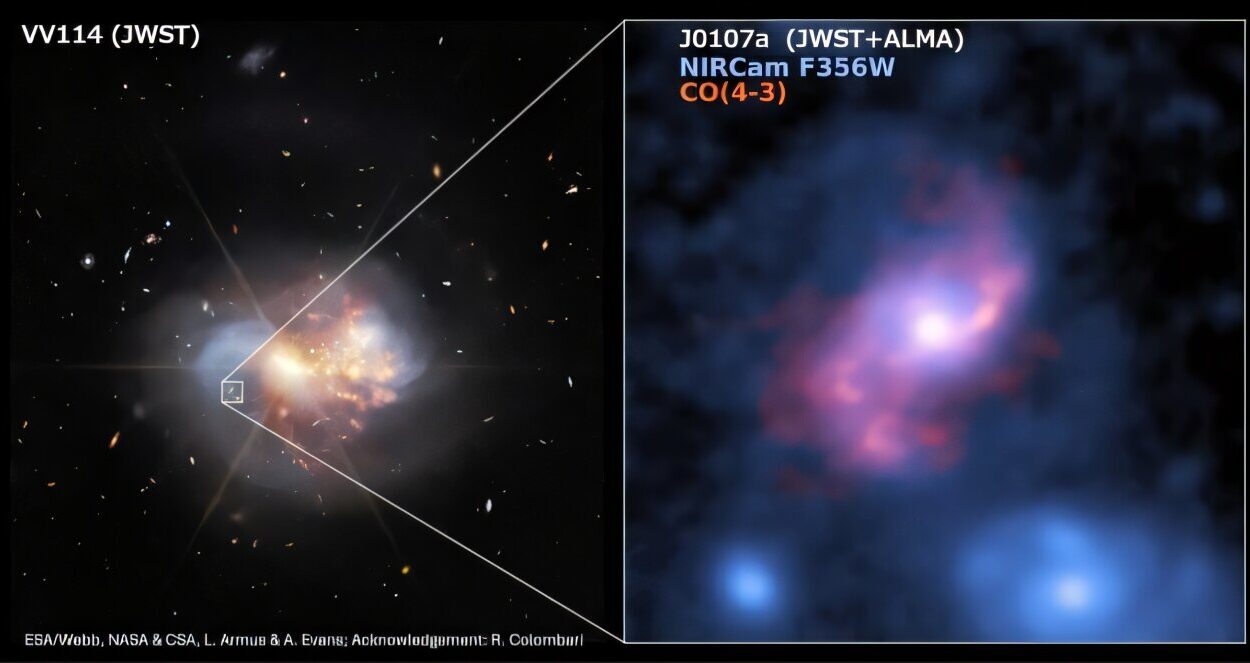

Approximately 110 days after the initial burst, the James Webb Space Telescope turned its gaze toward the location of GRB 250314A. Using its Near-Infrared Camera, known as NIRCAM, JWST was able to do something no telescope had done before in this context. It separated the fading light of the explosion from the faint, underlying galaxy in which it occurred.

This was the key moment. The data revealed a supernova emerging at precisely the same sky location as the earlier gamma-ray burst. The team had captured direct evidence linking the burst to the explosive death of a massive star in the early universe.

Dr. Antonio Martin-Carrillo, a co-author of the study and an astrophysicist at UCD School of Physics, described the significance of this observation in clear terms. “The key observation, or smoking gun, that connects the death of massive stars with gamma-ray bursts is the discovery of a supernova emerging at the same sky location. Almost every supernova ever studied has been relatively nearby to us, with just a handful of exceptions to date. When we confirmed the age of this one, we saw a unique opportunity to probe how the universe was there and what type of stars existed and died back then.”

Testing the Universe Against Familiar Stars

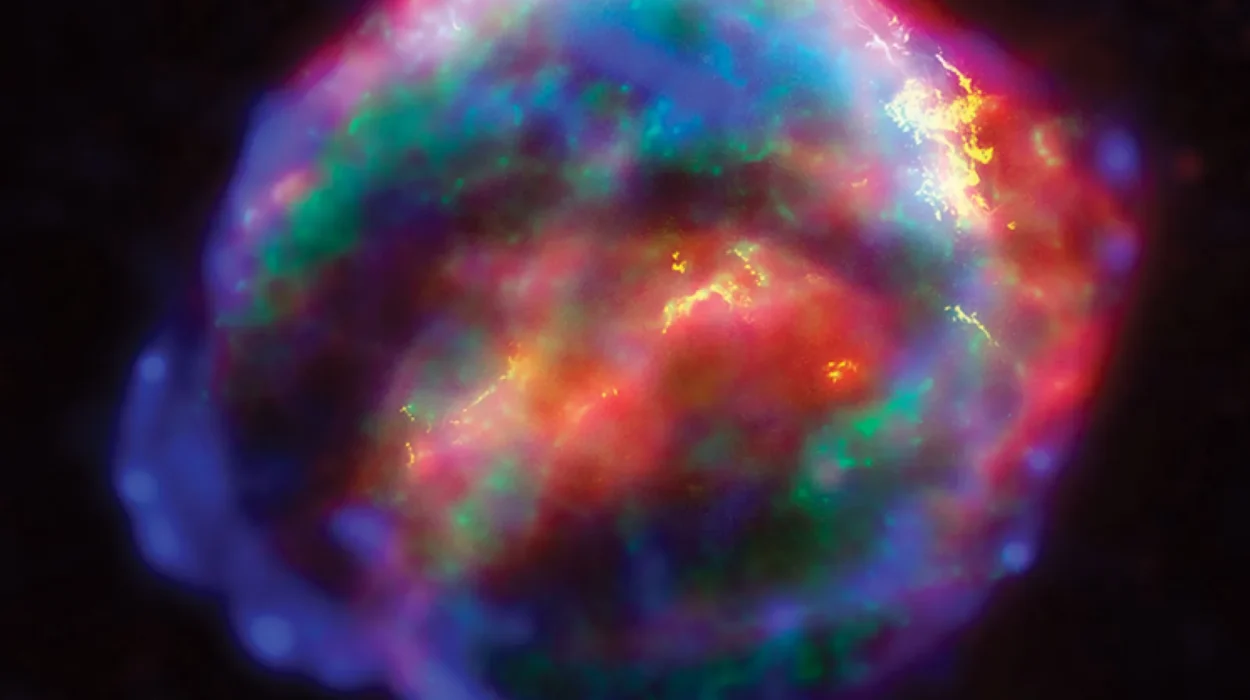

Seeing the supernova was only the beginning. The next question was what kind of explosion it was. The early universe was a very different place, with physical conditions unlike those we see around us today. In particular, stars formed under extremely low-metallicity conditions, meaning they contained fewer heavy elements than modern stars.

Many scientists had assumed that such stars would die in dramatically different ways, perhaps producing brighter or bluer explosions. To test this idea, the team turned to models based on supernovae associated with gamma-ray bursts in the local universe.

“Using models based on the population of supernovae associated with GRBs in our local universe, we made some predictions of what the emission should be and used it to propose a new observation with the James Webb Space Telescope,” Dr. Martin-Carrillo explained. “To our surprise, our model worked remarkably well and the observed supernova seems to match really well the death of stars that we see regularly. We were also able to get a glimpse of the galaxy that hosted this dying star.”

The observations showed that the distant supernova was surprisingly similar in brightness and spectral properties to SN 1998bw, the prototype gamma-ray-burst-associated supernova observed much closer to home. This similarity was striking. Despite the enormous gap in time and the vastly different cosmic environment, the explosion looked familiar.

A Challenge to Long-Held Assumptions

This resemblance carried profound implications. If a massive star in the early universe could collapse and explode in much the same way as stars observed locally, then some assumptions about early stellar evolution may need to be reconsidered.

The data suggested that the progenitor of GRB 250314A was not significantly different from the massive stars that produce gamma-ray bursts in the modern universe. This held true even though the early universe had lower metallicity and other distinct physical conditions.

The team also ruled out a far more luminous scenario, such as a superluminous supernova. The explosion simply did not match the expected brightness or behavior of those extreme events. Instead, it fit comfortably within the known family of GRB-associated supernovae.

At the same time, the findings raised new questions. If early stars were expected to behave differently, why does this one look so ordinary? Is this uniformity common, or is this supernova an exception? With only one such observation so far, the answers remain just out of reach.

A Galaxy Revealed Through a Fading Light

Beyond the supernova itself, the observations offered a rare glimpse of its host galaxy. At such distances, galaxies are incredibly faint and difficult to study. The fading of the supernova’s light over time is not a drawback but an opportunity.

The research team plans to obtain a second epoch of observations with JWST in the next one to two years. By then, the supernova is expected to have faded by more than two magnitudes. This dimming will allow astronomers to completely characterize the properties of the host galaxy and confirm precisely how much light came from the supernova itself.

This careful separation of light sources will provide a clearer picture of the environment in which the star lived and died, offering clues about star formation and galaxy evolution during the era of reionization.

Why This Discovery Matters

This detection marks a turning point in the study of the early universe. For the first time, astronomers have directly observed a supernova linked to a gamma-ray burst at such an extreme distance, offering a tangible connection between the deaths of massive stars and the conditions that existed when the first galaxies were taking shape.

The discovery provides a powerful anchor point for understanding stellar evolution in the universe’s earliest epochs. It shows that at least some massive stars in the early universe lived and died in ways that are remarkably similar to those seen today. This challenges assumptions about how drastically different early stellar explosions should be and suggests a surprising continuity across cosmic time.

At the same time, it opens new questions about why this uniformity exists and whether it holds true for other early stars. Each future observation will help refine our understanding of how the universe evolved from its youth into the richly structured cosmos we inhabit now.

In capturing the quiet afterglow of an ancient death, astronomers have gained more than a data point. They have gained a story, one that connects the earliest chapters of cosmic history to the familiar stellar lives and deaths we observe closer to home, reminding us that even in the universe’s childhood, the rhythms of creation and destruction may have already been well established.

More information: A. J. Levan et al, JWST reveals a supernova following a gamma-ray burst atz≃ 7.3, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202556581