Gamma-ray bursts usually arrive like cosmic lightning strikes. They flare brilliantly and vanish almost as quickly, leaving astronomers scrambling to capture the afterglow before it fades into memory. But on 2 July 2025, the universe behaved differently. Instead of a brief flash, the alerts kept coming. Bursts repeated. Minutes stretched into hours. By the time the activity finally subsided, more than seven hours had passed.

The event would be named GRB 250702B, and with that name came a staggering realization: this was the longest gamma-ray burst humans have ever witnessed.

Gamma-ray bursts are among the most powerful explosions in the universe, second only to the Big Bang itself. They are usually fleeting, so brief that their violence feels almost secretive. GRB 250702B refused to be secret. It lingered, pulsed, and demanded attention, rewriting expectations about how long such events can last.

A Signal Caught in the Act

The first alarm came from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which detected the initial bursts of gamma-rays and quickly pinpointed their location in X-rays. As soon as the coordinates were shared, astronomers across the world began turning their instruments toward the source. This was not just another burst. Something unusual was unfolding, and it was unfolding slowly enough to be followed.

Space-based telescopes led the charge, but ground-based observatories soon joined in. Each wavelength of light offered a different clue, a different perspective on the unfolding mystery. Was this event happening inside our own galaxy, or far beyond it? For a time, the answer was unclear.

That uncertainty ended when infrared observations from ESO’s Very Large Telescope revealed that GRB 250702B was located in a galaxy outside the Milky Way. The question of distance was settled, but the deeper questions were only beginning.

Following the Fading Echo

Once the initial blaze of gamma-rays dimmed, what remained was the afterglow: the fading light that follows a gamma-ray burst and carries within it a record of what just happened. Reading that record requires patience, precision, and powerful telescopes.

A team led by Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, set out to capture this afterglow as it evolved over time. Starting roughly 15 hours after the first detection and continuing for about 18 days, the team watched the light fade and change, knowing that every subtle shift could hold meaning.

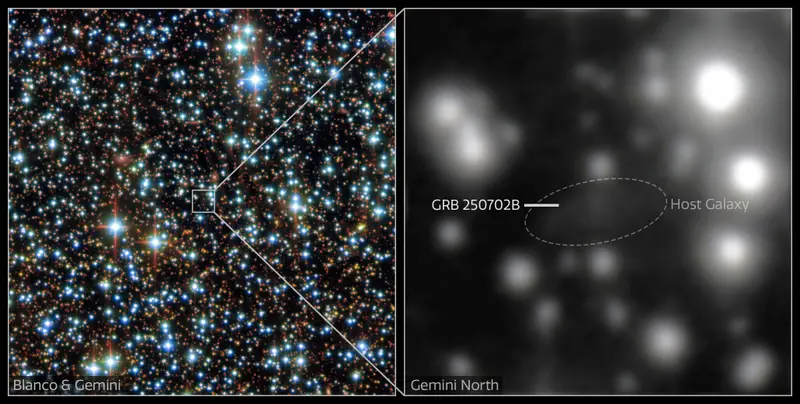

They relied on three of the world’s most capable ground-based observatories: the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope in Chile and the twin 8.1-meter telescopes of the International Gemini Observatory, one in Hawai‘i and one in Chile. Together, these telescopes formed a watchful network, tracking the afterglow long after the initial explosion had ended.

The results of this effort were published on 26 November in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, capturing not just data, but a story written in light.

Racing the Clock with Giant Eyes

Observing a transient event like a gamma-ray burst is a race against time. The universe does not wait for schedules or convenience. Telescopes must move quickly, sometimes within hours, to catch phenomena that will never repeat.

“The ability to rapidly point the Blanco and Gemini telescopes on short notice is crucial to capturing transient events such as gamma-ray bursts,” says Carney. “Without this ability, we would be limited in our understanding of distant events in the dynamic night sky.”

The team used an array of instruments to piece together the picture. On the Blanco telescope, they employed the NEWFIRM wide-field infrared imager and the massive 570-megapixel Dark Energy Camera. On Gemini North and Gemini South, they used the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs. Each instrument contributed a different layer of detail, revealing aspects of the burst invisible to the others.

A Burst Hidden Behind Dust

As the data accumulated, a surprising pattern emerged. GRB 250702B could not be seen in visible light. At first glance, this might seem unremarkable, but the reasons behind it were telling.

Some of the obscuration came from dust within our own Milky Way galaxy. But most of it originated much farther away, in the host galaxy where the burst itself occurred. The light was being swallowed, scattered, and dimmed before it ever reached Earth.

Gemini North provided the only detection close to visible wavelengths, and even that faint glimpse required nearly two hours of observation to pull the signal from beneath thick swaths of dust. This was not a clean, open environment. The burst had gone off in a place dense with obscuring material.

Weaving a Complete Picture

To understand what could produce such a long-lasting and dust-shrouded burst, Carney and his team expanded their dataset even further. They combined their observations with new data from the Keck I Telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory, along with publicly available observations from the Very Large Telescope, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, and X-ray and radio observatories.

This growing archive of information was then compared with theoretical models. These models serve as structured explanations of how astronomical phenomena behave, allowing scientists to test whether observed data match predicted outcomes.

Through this careful comparison, a clearer picture began to emerge. The initial gamma-ray signal was most likely produced by a narrow, extremely fast jet of material slamming into surrounding matter. This kind of outflow is known as a relativistic jet, and its interaction with its environment can produce intense, long-lasting emissions.

The environment itself proved just as important as the jet. The data showed that the area around the burst was rich in dust, and that the host galaxy was extremely massive compared to most galaxies known to host gamma-ray bursts. The GRB likely occurred in a dense, dusty region, possibly along a thick lane of dust that lay directly between Earth and the source.

An Explosion That Defies Categories

Since gamma-ray bursts were first recognized in 1973, roughly 15,000 have been observed. Only about a half dozen approach the extraordinary length of GRB 250702B. Those rare events have inspired a range of explanations, including the collapse of blue supergiant stars, tidal disruption events, or the birth of magnetars.

Yet GRB 250702B does not fit neatly into any of these categories.

Based on the available data, scientists have proposed several possible scenarios. One involves a black hole falling into a star that has already lost its hydrogen and is composed almost entirely of helium. Another considers a star, or even a sub-stellar object like a planet or brown dwarf, being torn apart during a close encounter with a compact object such as a stellar black hole or neutron star, an event known as a micro-tidal disruption event.

A third possibility is perhaps the most tantalizing. The burst could have been caused by a star being shredded as it fell into an intermediate-mass black hole. These black holes, with masses ranging from one hundred to one hundred thousand times that of the Sun, are believed to exist in abundance but have been notoriously difficult to find. If this scenario proves correct, GRB 250702B would mark the first time humans have witnessed a relativistic jet from an intermediate-mass black hole actively consuming a star.

For now, the data remain consistent with these novel explanations, but none can yet be confirmed.

Listening to the Universe’s Ancient Echoes

“This work presents a fascinating cosmic archaeology problem in which we’re reconstructing the details of an event that occurred billions of light-years away,” says Carney. “The uncovering of these cosmic mysteries demonstrates how much we are still learning about the universe’s most extreme events and reminds us to keep imagining what might be happening out there.”

The phrase cosmic archaeology feels especially apt. Like archaeologists brushing dust from ancient artifacts, astronomers are piecing together the story of an explosion that happened unimaginably far away and unimaginably long ago. Every photon collected is a fragment of that story, preserved across cosmic time.

Why This Discovery Matters

GRB 250702B matters because it challenges what scientists thought they knew about gamma-ray bursts. Its unprecedented length, dusty environment, and massive host galaxy suggest that there are pathways to these extreme explosions that remain poorly understood. It expands the known range of cosmic behavior and hints at processes that may be rare, hidden, or easily missed.

This event also demonstrates the power of coordinated observation. Space-based detectors, ground-based telescopes, and theoretical models worked together to capture a fleeting yet profound phenomenon. Without rapid response and sustained follow-up, GRB 250702B might have been recorded as an anomaly rather than explored as a clue.

Most of all, this research matters because it reminds us that the universe still holds surprises. Even among the most violent and well-studied phenomena known, there are events that refuse to conform, that stretch the limits of understanding and invite deeper curiosity. GRB 250702B is not just the longest gamma-ray burst ever observed. It is a message from the cosmos that the story of extreme events is far from complete, and that the universe still has much to teach those who are watching closely.

More information: Jonathan Carney et al, Optical/Infrared Observations of the Extraordinary GRB 250702B: A Highly Obscured Afterglow in a Massive Galaxy Consistent with Multiple Possible Progenitors, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae1d67