For centuries, humanity has watched the skies with a mixture of wonder and caution. From ancient civilizations who feared falling stars to modern astronomers tracking near-Earth objects, we have always known that space can be both beautiful and dangerous. Yet, a new international study led by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Brazil suggests that we may not be seeing the full picture. Hidden in the bright glare of the Sun, a class of asteroids—known as Venusian co-orbitals—may be quietly circling the star, invisible to our telescopes, but capable of one day threatening Earth with catastrophic impacts.

These asteroids do not belong to the well-studied asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Instead, they move much closer to us, sharing the orbit of Venus in a delicate cosmic dance. For now, they remain hidden, but simulations reveal they may eventually drift into Earth-crossing paths. If such an object, even just a few hundred meters wide, were to collide with our planet, it could release energy equivalent to hundreds of nuclear weapons and devastate an entire region.

What Makes Venusian Co-Orbitals So Mysterious

To understand why these asteroids are so elusive, it helps to grasp the nature of their orbits. A Venusian co-orbital asteroid does not orbit Venus directly. Instead, it circles the Sun, but in such a way that it remains in a 1:1 resonance with Venus—meaning it takes the same amount of time to complete a revolution around the Sun as the planet does.

This resonance places them in a region of space very close to the Sun as seen from Earth, where the blinding glare makes observation nearly impossible. Unlike the stable “Trojan” asteroids of Jupiter, which can linger near the planet’s gravitationally balanced points for millions of years, Venus’s co-orbitals are far less stable. They shift and wander over cycles of about 12,000 years, sometimes hugging Venus’s orbit, other times drifting closer to Earth.

During these transitional phases, the asteroids can cross Earth’s orbital path. And while the probability of immediate collision is low, the statistical models show that, over thousands of years, these near-misses could eventually translate into impacts.

The Role of Eccentricity: Why Some Are More Dangerous

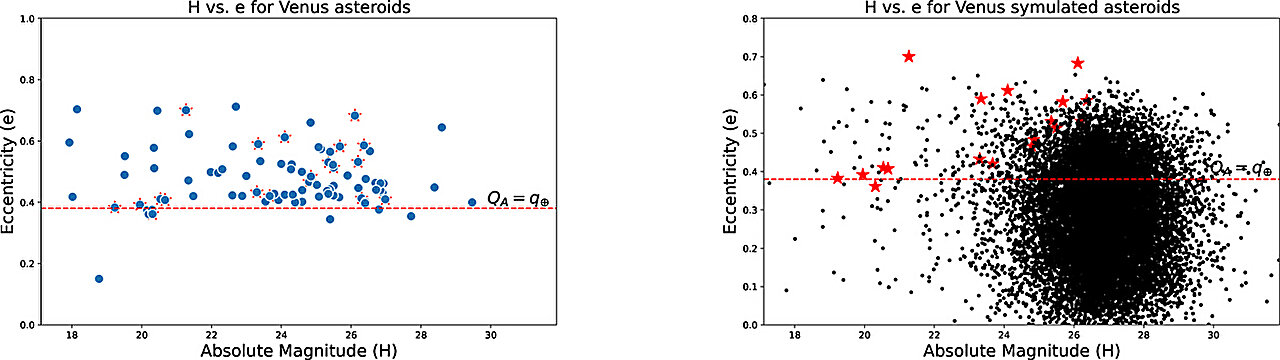

One of the most fascinating aspects of the study lies in orbital eccentricity—the measure of how circular or stretched out an orbit is. Earth’s orbit is nearly circular, with an eccentricity of just 0.017. But most known Venusian co-orbitals have eccentricities greater than 0.38, meaning their paths are elongated, pulling them farther from the Sun and into regions of the sky where telescopes can occasionally spot them.

However, the simulations suggest that this is only part of the story. There may be a much larger, unseen population of low-eccentricity Venusian co-orbitals—asteroids whose orbits are almost circular and thus keep them close to the Sun’s glare at all times. From Earth’s perspective, these hidden asteroids would be virtually undetectable, escaping even our most powerful ground-based observatories. And paradoxically, the less eccentric their orbit, the greater the risk they pose, because they remain confined to orbital paths that can eventually intersect with Earth’s.

What Simulations Reveal About Potential Collisions

The UNESP research team used advanced numerical simulations to test what could happen if such hidden objects exist. The results were sobering. Some simulated asteroids came within distances so small that, on astronomical timescales, collisions would be almost inevitable.

Even a single asteroid 300 meters wide—a relatively modest size in cosmic terms—could create a crater up to 4.5 kilometers across. The energy released would measure in the hundreds of megatons, dwarfing the most powerful nuclear bombs ever built. While an impact in an unpopulated region might cause limited damage, a strike on or near a city could bring devastation on a continental scale.

The Challenge of Detection

Why can’t we see them? The answer lies in the geometry of observation. Ground-based telescopes typically avoid looking too close to the Sun for safety reasons and because the sky’s brightness washes out faint objects. Even with cutting-edge facilities like the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, which is expected to revolutionize asteroid detection, the chances of catching a Venusian co-orbital remain slim.

According to the study, even the brightest of these asteroids would only be visible for a brief period—perhaps one or two weeks—when they rise more than 20 degrees above the horizon. And these opportunities would occur infrequently, separated by months or even years. This leaves long stretches of time during which dangerous objects could pass undetected.

Looking Beyond Earth for Solutions

If Earth’s vantage point blinds us, the solution may lie in space. Space-based telescopes designed to observe regions close to the Sun could finally uncover these hidden threats. Missions like NASA’s upcoming Neo Surveyor and China’s proposed Crown project are specifically intended to monitor low solar elongations, where ground-based observatories cannot look.

By positioning telescopes beyond Earth’s atmosphere and closer to the Sun’s direction, scientists could maintain continuous surveillance of regions where Venusian co-orbitals hide. Such missions may become vital to planetary defense, not just for discovering asteroids, but for giving humanity time to act if one is ever found on a collision course.

Where Do These Asteroids Come From?

The origins of Venusian co-orbitals are as intriguing as their potential threat. Unlike the asteroid belt, which holds remnants of planetesimals that never formed a planet because of Jupiter’s gravitational influence, these objects likely migrated inward. Over millions of years, gravitational interactions with the giant planets—especially Jupiter and Saturn—nudged some asteroids into the inner solar system. Eventually, a few were temporarily captured in resonance with Venus, where they now linger.

But these captures are fleeting. On average, a Venusian co-orbital will remain in resonance for about 12,000 years before evolving into a new orbit—one that could lead it closer to Earth or fling it out of the solar system entirely. This instability makes them both fascinating and dangerous: they are cosmic wanderers whose paths may eventually cross our own.

Why This Research Matters

For now, no known Venusian co-orbital poses an immediate threat. But the research highlights an unsettling reality: planetary defense strategies that focus only on easily observed near-Earth objects may leave us blind to an entire population of hidden dangers. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

As Professor Valerio Carruba of UNESP, the study’s lead author, warns, planetary defense must account for not only what we can see, but also what remains invisible. Recognizing this blind spot is the first step toward building a more complete strategy for protecting our planet.

Humanity’s Place in the Cosmos

The story of Venusian co-orbital asteroids is a reminder of our fragile place in the cosmos. Earth, for all its beauty and resilience, is vulnerable to celestial hazards. Yet it is also a testament to human ingenuity that we can even identify such threats—through mathematical models, computer simulations, and the dedication of astronomers who peer into the unknown.

Every discovery like this adds to a larger narrative: humanity’s effort to survive and thrive in a universe that is both nurturing and perilous. We cannot change the laws of celestial mechanics, but we can prepare, detect, and respond. In doing so, we honor the deep bond between human curiosity and cosmic awareness.

A Call for Vigilance

The asteroids hidden in Venus’s orbit may never strike Earth. But they exist as a reminder that the universe is dynamic and unpredictable. By acknowledging their presence and developing new ways to observe them, we strengthen our planetary defenses and reaffirm our responsibility to safeguard the only home we know.

In the end, the story of Venusian co-orbital asteroids is not just about rocks in space. It is about us—our capacity to see the unseen, to anticipate the unlikely, and to prepare for the future. It is about our ongoing struggle to live wisely under the stars, aware of the risks, but also inspired by the endless beauty of the cosmos.

More information: V. Carruba et al, The invisible threat: Assessing the collisional hazard posed by undiscovered Venus co-orbital asteroids, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202554320