For generations, the story of human evolution has been told as a steady climb toward dominance. We imagine our ancestors as clever hunters who outsmarted predators and gradually secured their place at the top of the food chain. Among them, Homo habilis—often celebrated as the “handy man” for its tool-making skills—has long been viewed as one of the first humans to tip the balance in favor of prey becoming predator. But a new study is challenging this familiar narrative, suggesting that life for these early humans may have been far more precarious than we once believed.

Researchers from the University of Alcalá in Spain have used cutting-edge technology to peer back nearly two million years into the past, and what they found paints a very different picture of our early relatives. Instead of fearless hunters, Homo habilis may have been living under constant threat, stalked and killed by big cats that roamed the African savanna.

Ancient Bones, Modern Technology

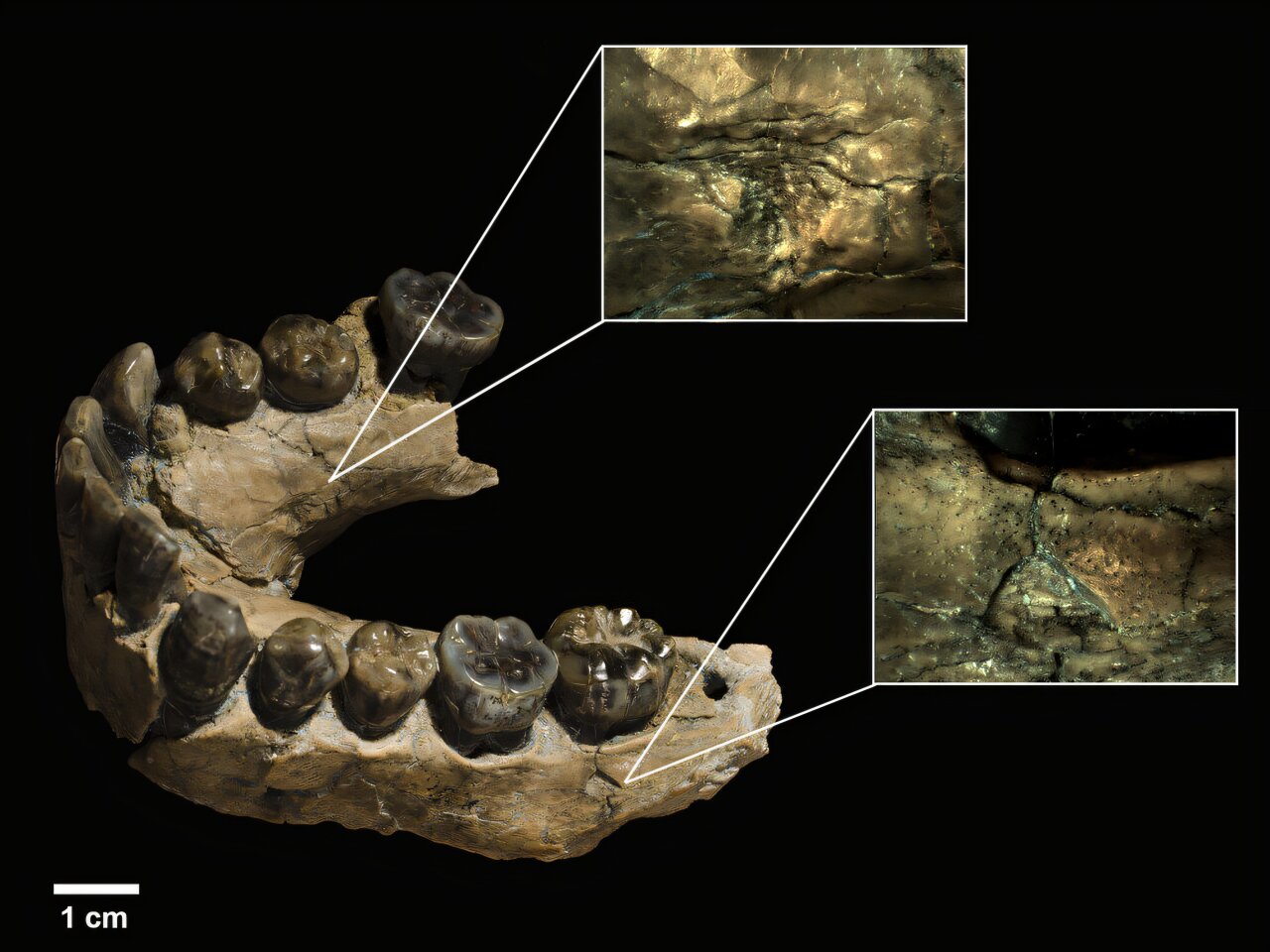

The evidence comes from two Homo habilis fossils discovered decades ago in Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world. These remains, dating back about 1.8 to 2 million years, carry tiny scars—marks left behind by teeth that tore through flesh and bone. For years, researchers debated what had caused them. Were they the result of scavengers feeding on already-dead bodies, or the signatures of predators striking down living prey?

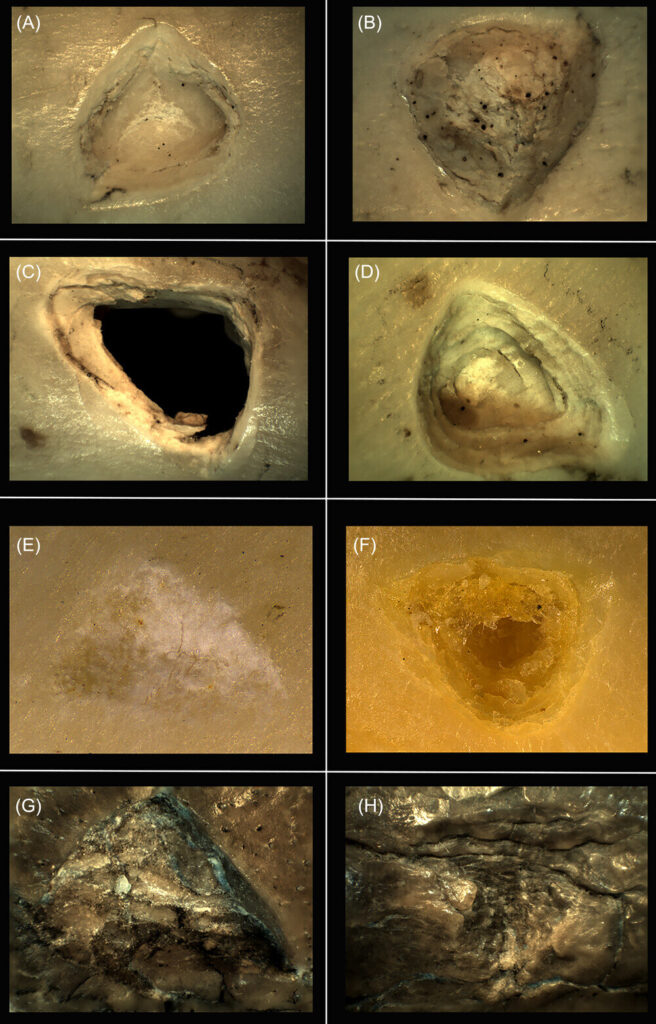

To settle the question, the Spanish team turned to artificial intelligence. They trained computer models on a library of nearly 1,500 images showing tooth marks left by modern carnivores—lions, leopards, crocodiles, wolves, and hyenas. Each predator leaves behind a distinctive pattern, much like a fingerprint, shaped by the size and form of its teeth and the way it feeds.

When the AI analyzed the marks on the Homo habilis bones, the results were striking. With more than 90 percent probability, the tooth pits were matched to those made by leopards. The triangular shape of the marks, along with their spacing, closely mirrored those in the reference images.

The Precarious Life of Homo habilis

This conclusion carries weighty implications. If leopards were actively preying on Homo habilis, it suggests that these early humans were not yet masters of their environment. Instead, they were still vulnerable creatures, sharing the same ecological niche as their australopithecine predecessors—smaller-bodied primates who often found themselves on the menu for larger carnivores.

The researchers point out that if H. habilis had been a dominant force, competing successfully with predators, we would expect their remains to show signs of scavenging by bone-crushing animals like hyenas after natural deaths. But the clean, fresh bite marks suggest something much more violent: death at the jaws of a leopard.

This paints a vivid picture of daily life. Imagine the African plains nearly two million years ago—an environment alive with danger. Leopards prowled the grasses, their spotted coats blending seamlessly with the terrain. At night, when H. habilis might have sought shelter in trees or caves, these predators could have struck, dragging victims into the darkness. Survival was a constant gamble, with sharp senses and quick reflexes serving as the only defenses against predators far more powerful.

A Turning Point in Human Evolution

If Homo habilis was still prey, when did humans begin to reverse the balance? The study suggests that the shift came later, as brain size increased, tools became more sophisticated, and cooperation grew more advanced in species like Homo erectus. Fire, hunting strategies, and the ability to work in groups eventually gave our ancestors the edge. But in the time of H. habilis, humans were just one species among many, struggling to survive in a predator-rich world.

This realization does not diminish the importance of H. habilis. On the contrary, it highlights the resilience of our lineage. These early humans lived through constant threat, yet they endured, adapted, and laid the foundation for the evolutionary leaps to come. Their story reminds us that dominance over nature was not a birthright but a hard-won achievement.

AI as a Time Machine into the Past

Beyond its revelations about Homo habilis, the study underscores a powerful new tool in archaeology: artificial intelligence. By training machines to recognize patterns invisible to the human eye, researchers can revisit old evidence and uncover fresh insights. The tooth marks on these fossils had been studied before, but the precision of AI allowed for a new level of certainty.

This is just the beginning. In the future, AI could help identify predator-prey relationships across other fossil records, shed light on the diets of ancient species, or even clarify how early humans interacted with each other and their environments. It offers a way to ask new questions of old bones, breathing life into stories that seemed already written.

Rethinking What It Means to Be Human

Perhaps the most profound takeaway is how this discovery reshapes our self-image. We like to think of humanity as destined for greatness, a species that rose inevitably to rule the world. But the truth is far more humbling. For much of our history, we were fragile beings, preyed upon like any other animal. Our ancestors survived not because they were invincible but because they adapted, endured hardship, and slowly, painstakingly, found ways to tilt the odds in their favor.

In this light, the story of Homo habilis becomes a story of vulnerability, struggle, and resilience. It is a reminder that our journey to dominance was neither straight nor guaranteed. It was forged in fear, in danger, and in the shadow of predators that once saw us not as hunters, but as prey.

And perhaps that is the greater lesson: our strength as humans has always been born out of weakness. By understanding the perilous lives of our ancestors, we gain not only a clearer view of the past but also a deeper appreciation for the extraordinary, fragile, and hard-won path that led us to where we are today.

More information: Marina Vegara‐Riquelme et al, Early humans and the balance of power: Homo habilis as prey, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nyas.15321