For centuries, Brusselstown Hill rose quietly over County Wicklow, its grassy slopes giving little hint of the human intensity that once pulsed across its surface. To passersby, it may have seemed like just another ancient hillfort, one of many scattered across Ireland’s landscapes. But recent research has revealed that this hill was anything but ordinary. Beneath its earthworks lay the footprint of an enormous, tightly packed community, a place where hundreds of homes once clustered together in a way prehistoric Ireland was never supposed to have known.

In a study published in Antiquity, Dr. Dirk Brandherm and his colleagues uncovered evidence that transforms Brusselstown Ring into something unprecedented. More than 600 suspected house platforms were identified within the hillfort, making it the largest nucleated settlement ever discovered in prehistoric Britain and Ireland so far. What had once seemed like an isolated stronghold now appears to have been a densely inhabited hub, alive with daily routines, shared resources, and a scale of social organization that challenges long-held assumptions.

A Landscape Shaped Over Millennia

Brusselstown Ring does not stand alone. It belongs to the Baltinglass hillfort cluster, a remarkable concentration of hilltop enclosures in County Wicklow. Up to 13 large enclosures form this cluster, and together they tell a story of long-term human engagement with the landscape. Evidence shows continuous use and monumental construction stretching from the Early Neolithic through to the Bronze Age, roughly between 3700 and 800 BC.

Within this setting, Brusselstown Ring stands out for both its size and its unusual design. Two widely spaced ramparts surround the enclosure, creating a vast fortified area. The outermost enclosing element is especially striking, as it encompasses not only Brusselstown Ring itself but also the Neolithic enclosure of Spinas Hill 1. Hillforts that span more than a single hill are exceedingly rare in Britain and Ireland, and even on continental Late Iron Age Europe they are uncommon.

This sprawling layout suggests deliberate planning and a vision that extended beyond simple defense. The builders of Brusselstown Ring were shaping a place meant to contain something large, complex, and enduring.

When the Air Revealed a Hidden City

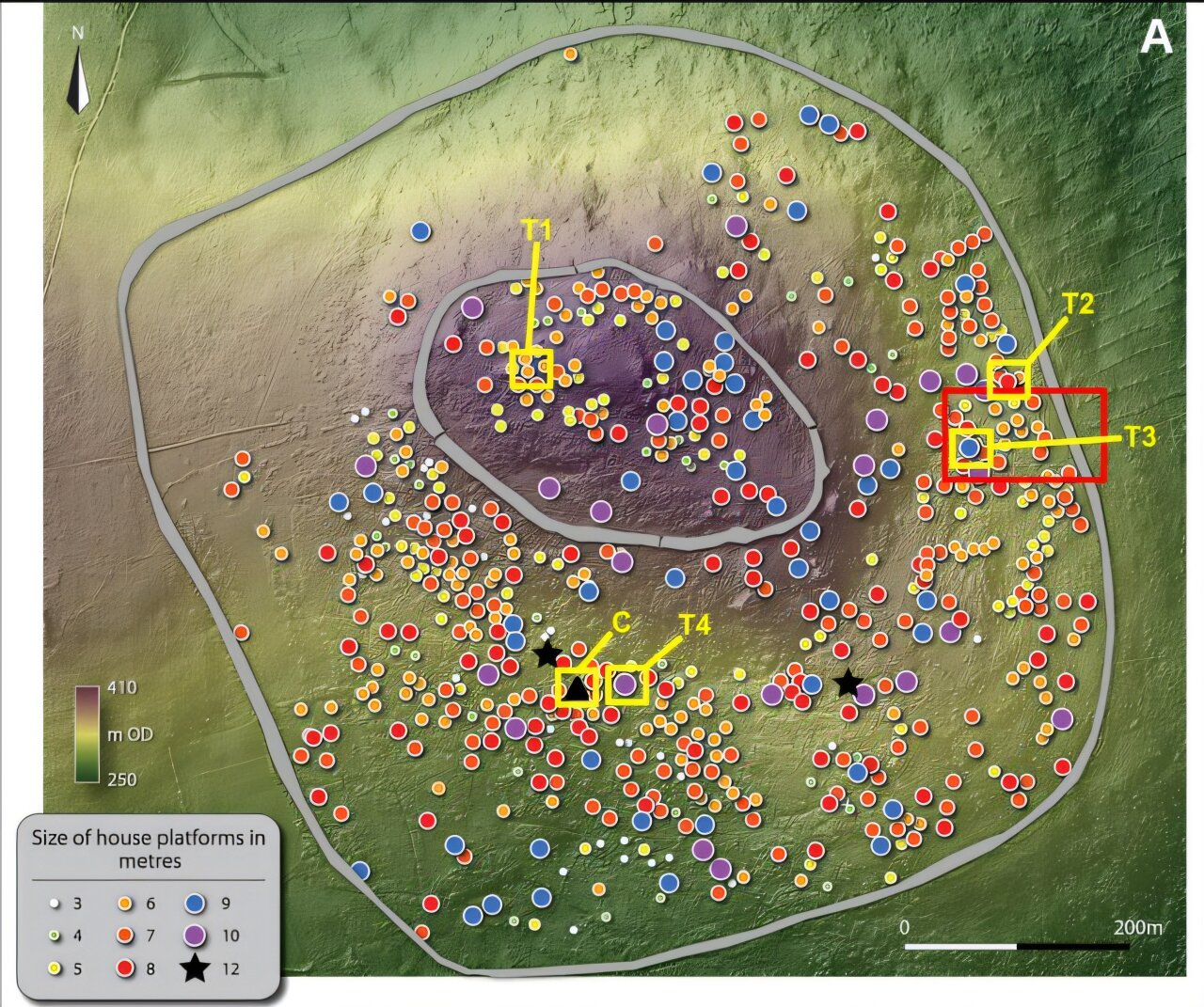

The true scale of Brusselstown Ring emerged not from traditional excavation alone, but from airborne surveys that traced subtle features invisible from the ground. These surveys revealed more than 600 suspected house platforms spread across the hillfort. Ninety-eight were located within the inner enclosure, while the remaining 509 lay between the inner and outer enclosing elements.

The numbers alone are staggering. Prehistoric Irish settlements are typically small, often consisting of just one to five dwellings. Here, by contrast, was a settlement that dwarfed those norms, suggesting a level of population density rarely associated with this period or region.

Dr. Cherie Edwards highlighted just how transformative this discovery is, saying, “Brusselstown Ring presents an intriguing case for understanding settlement dynamics in Ireland during the Bronze Age. This site—along with a small number of other nucleated settlements situated on hilltops—appears to have emerged around 1200 BC. This pattern contrasts sharply with the more typical form of prehistoric Irish settlements, which generally consist of one to five dwellings. Such evidence suggests that proto-urban development in Northern Europe may have occurred nearly 500 years earlier than traditionally recognized.”

The idea that something resembling urban life could have taken root this early forces a reconsideration of how communities formed and functioned in prehistoric Northern Europe.

Digging Into Daily Life

To move beyond surface impressions, researchers needed to understand how this settlement actually operated. Radiocarbon dating was combined with four carefully chosen test excavations to probe the lives of the people who once lived there.

Dr. Edwards explained the results, stating, “The settlement clearly dates to the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (c. 1193–410 BC) and represents a nucleated or agglomerated site characterized by a high density of dwellings.”

The excavation trenches were not placed at random. Instead, they targeted house platforms of different sizes, ranging from six meters to twelve meters in diameter. The goal was to see whether larger houses indicated higher status or wealth, and whether architectural differences translated into social inequality.

“Excavation trenches were deliberately positioned over house platforms of varying diameters (6 m, 7 m, 8 m, and 12 m) to assess potential correlations between house size and indicators of social differentiation. Specifically, this approach sought to determine whether architectural variation corresponded with differences in the quantity or type of artifacts recovered.”

The results were unexpected. Radiocarbon dating showed that houses of all sizes were occupied at the same time. More strikingly, the artifacts recovered from each structure showed no meaningful differences.

“Radiocarbon dating results demonstrate that houses of all sizes were occupied contemporaneously, and no discernible differences were found in the artifactual assemblages associated with each structure. Although preliminary, these findings align with broader patterns observed at other Bronze Age domestic sites in Ireland, which similarly lack material evidence for wealth differentiation or social hierarchy.”

In a settlement of extraordinary size, there was little sign of social division. The people of Brusselstown Ring appear to have lived in a remarkably even community, at least as far as the material record can show.

Following the Path of Water

Among the many features uncovered during survey work was a structure that did not fit neatly into known categories. Near one of the excavation trenches, researchers identified a flat interior outlined by large stones. This was unusual, especially since roundhouses at the site did not typically have such a configuration.

Clues from earlier surveys added another layer to the mystery. A stream was known to flow into the structure from a rocky outcrop uphill. Combined with its shape and size, this raised a compelling possibility. The structure might be a Bronze and Iron Age water cistern, similar to those found elsewhere in Europe.

For a settlement of this scale, water would have been essential. Housing hundreds of people on a hilltop would have required reliable access to freshwater. If this structure is confirmed as a cistern, it would be the first of its kind identified in an Irish hillfort.

Such a finding would not only highlight the engineering skills of the site’s inhabitants but also deepen understanding of how large prehistoric communities managed resources and sustained daily life.

A Gradual Ending, Not a Sudden Fall

Despite its scale and apparent success, Brusselstown Ring was eventually abandoned. Understanding why remains an open question, but the research offers important clues.

More work is needed to clarify the nature and chronology of the enclosing elements and to fully understand the possible water cistern. Yet the broader pattern of abandonment appears to align with trends seen elsewhere.

Dr. Edwards noted, “The site’s chronological trajectory aligns closely with that of other, albeit smaller, hilltop nucleated sites in Ireland, implying that its abandonment followed a broader regional pattern of gradual decline during the Iron Age, around the third century BC. This decline also appears unrelated to the climatic shift toward cooler and wetter conditions that began during the Bronze Age–Iron Age transition, ca. 750 BC.”

Rather than a dramatic collapse triggered by environmental stress, Brusselstown Ring seems to have faded as part of a wider transformation in how communities organized themselves across the region.

Why This Discovery Changes the Story

Brusselstown Ring forces a quiet but profound rewrite of prehistoric history in Ireland and beyond. It shows that large, densely populated settlements existed far earlier than traditionally believed, and that these communities could function without clear material signs of hierarchy or wealth division.

The discovery challenges the assumption that complexity and scale in settlement only emerged later, under different social or economic conditions. It suggests that people in the Late Bronze Age were experimenting with new ways of living together, testing the boundaries of cooperation, planning, and shared resources.

If proto-urban development truly began around 1200 BC in places like Brusselstown Ring, then the roots of European urbanism stretch deeper into the past than once imagined. The hilltop that once seemed silent now speaks clearly, telling a story of innovation, community, and possibility that reshapes how we understand the human past.

More information: Dirk Brandherm et al, Brusselstown Ring: a nucleated settlement agglomeration in prehistoric Ireland, Antiquity (2025). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2025.10247