Some stars are born wanderers. Others are pushed into motion by forces so extreme that they tear them away from everything they have ever known. For nearly a century, astronomers have watched these fugitives of the cosmos, called hypervelocity stars, because they move so fast that a galaxy’s gravity can no longer hold them. They are not merely curiosities streaking through space. They are messengers, carrying with them clues about the invisible architecture of the Milky Way.

Now, astronomers from China have found a new way to hunt these stellar runaways. By focusing on a special class of stars whose rhythmic pulsing acts like a cosmic heartbeat, they have conducted a large-volume search that reveals new populations of stars moving at astonishing speeds. Their work, published in The Astrophysical Journal, turns ancient, steadily pulsating stars into tools for probing some of the deepest mysteries of our galaxy.

The Speed Needed to Truly Escape

To understand why hypervelocity stars matter, it helps to imagine what it means to escape. Every object with mass exerts gravity, and to break free from that pull, an object must reach a certain speed. On Earth, that speed is 11.2 kilometers per second. A rock blasted off the surface by an asteroid impact can, if it reaches that speed, drift endlessly into space. A dramatic example may have occurred in 1957, when a steel lid covering a blast hole from an underground nuclear explosion in Nevada was reportedly launched upward at an estimated six times Earth’s escape velocity, unless it vaporized before leaving the atmosphere.

The numbers grow more dramatic as gravity deepens. To escape the sun entirely, a spacecraft needs to reach 618 kilometers per second, though from Earth’s position in orbit, the required speed is much lower, about 42 kilometers per second. On the scale of the Milky Way, escaping becomes an extraordinary challenge. From the sun’s position in the galaxy, the escape velocity is about 550 kilometers per second.

Hypervelocity stars do not merely meet this requirement. They surpass it. With tangential speeds of 1,000 kilometers per second or more, these stars are gravitationally unbound from the Milky Way. They are not orbiting the galaxy. They are leaving it.

A Violent Encounter at the Galactic Heart

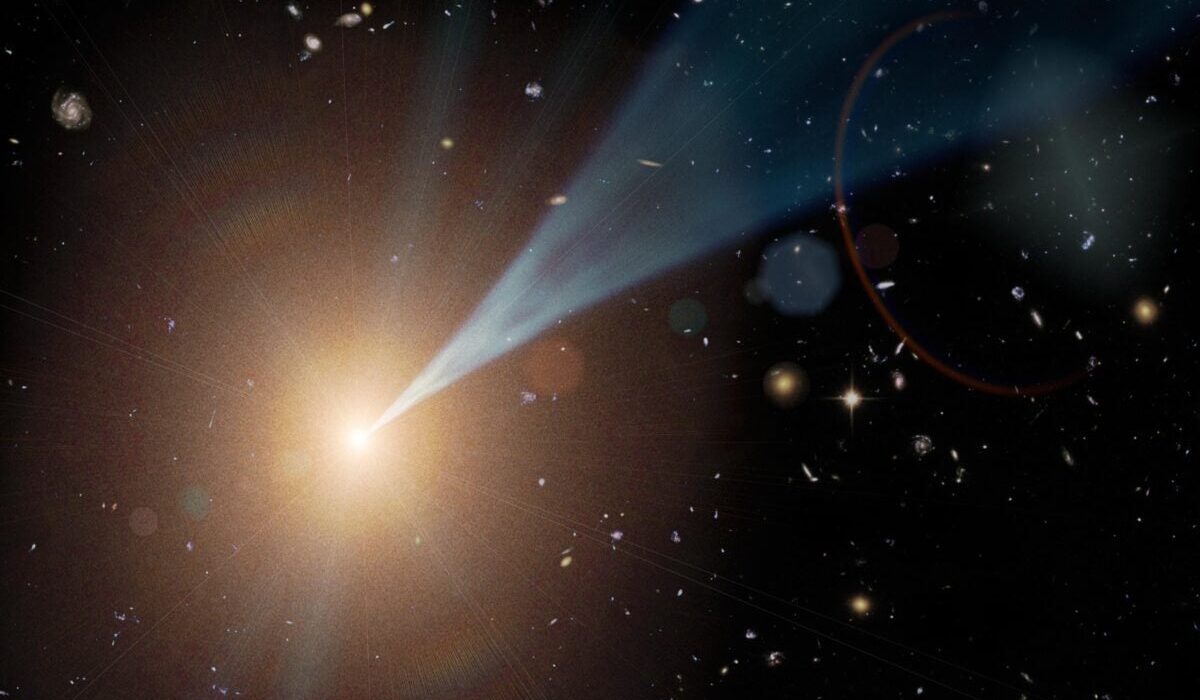

One of the most powerful engines capable of launching a star to such speeds sits at the very center of our galaxy. Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole anchoring the Milky Way, exerts a gravitational pull so intense that it can tear apart stellar partnerships.

This idea was formalized in 1988 by astronomer Jack Hills, who proposed what is now known as the Hills mechanism. In this scenario, a pair of stars bound together as a binary system strays too close to a supermassive black hole. The encounter is catastrophic. One star is captured by the black hole, locked into a tight orbit, while the other is violently flung outward, hurled away at incredible speed.

This was not just theory. In 2019, astronomers observed a star racing away from the Milky Way’s core at 1,755 kilometers per second, or 0.6% the speed of light. That speed exceeds the escape velocity of the galactic center, marking the star as a true cosmic exile. Such observations offer direct evidence for the existence and influence of supermassive black holes in galactic centers and provide rare insight into their properties.

Why Runaway Stars Are Cosmic Maps

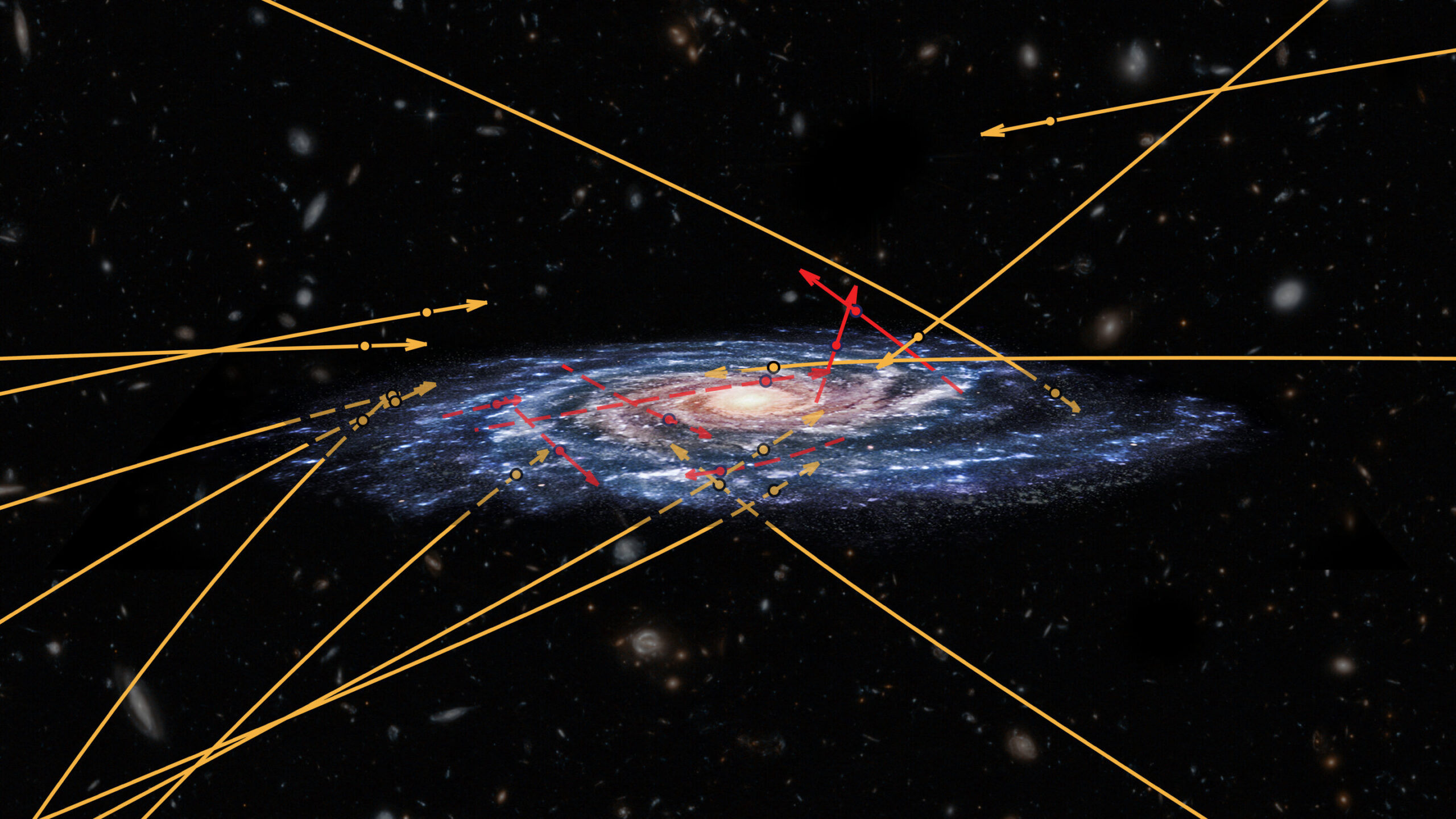

Hypervelocity stars do more than dramatize the power of gravity. By tracing their paths backward through space, astronomers can reconstruct the gravitational landscape of the Milky Way. These stars act like test particles flung through an invisible field, revealing how mass is distributed throughout the galaxy.

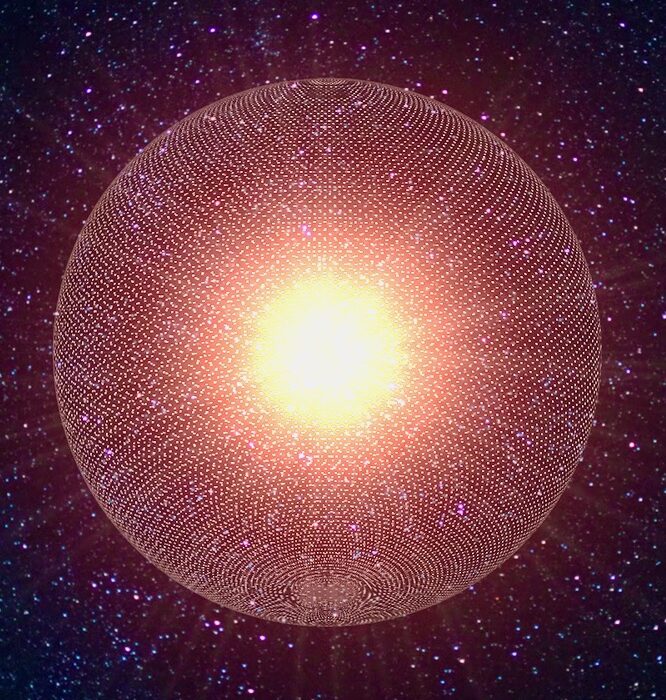

This includes the elusive dark matter halo, the vast spherical region surrounding the Milky Way’s disk. Dark matter does not emit light, making it impossible to see directly, but its gravitational influence shapes the motion of stars. When hypervelocity stars travel through the halo, their trajectories encode information about this hidden mass.

Understanding where these stars come from and how they move helps scientists refine their models of the galaxy’s gravitational potential. Each runaway star is a data point in a map of forces that cannot otherwise be drawn.

Listening to the Pulses of Ancient Stars

With these motivations in mind, a team of three astronomers from Beijing scientific institutions, led by Haozhu Fu of Peking University, turned their attention to a different kind of stellar messenger. Instead of searching among young, massive stars, they focused on RR Lyrae stars, often abbreviated as RRLs.

These stars are old giants, relics from the early history of the Milky Way. They pulse with remarkable regularity, their brightness rising and falling with periods between 0.2 and one day. They inhabit the thick disk and halo of the galaxy and are frequently found in globular clusters. The Milky Way contains more than 150 such clusters, about a third of them arranged in a nearly spherical halo around the galactic center.

What makes RR Lyrae stars especially valuable is that their intrinsic luminosity is well understood. There is a known relationship connecting their pulsing period, their absolute magnitude, and their metallicity, which astronomers define as the abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, referred to as “metals”. By comparing how bright these stars truly are with how bright they appear from Earth, astronomers can calculate their distances using the inverse-square distance relationship.

This makes RR Lyrae stars reliable cosmic mile markers, ideal for large-scale searches across the galaxy.

Sifting Through a Sea of Starlight

The team began with vast catalogs of RR Lyrae stars. One published catalog contained 8,172 such stars from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. An extended catalog expanded the field dramatically, listing 135,873 RR Lyrae stars with metallicity and distance estimates derived from Gaia photometry. These measurements come from the Gaia satellite, launched by the European Space Agency in 2013, which observes the brightness of stars with extraordinary precision.

But finding hypervelocity stars is not simply a matter of distance. Speed is the defining factor, and measuring speed requires careful spectroscopic data that can reveal how fast a star is moving away from or toward us. Most stars in the catalogs did not have radial velocity measurements with uncertainties low enough for this purpose.

After eliminating stars that did not meet these strict criteria, the researchers were left with a much smaller but far more relevant sample of 165 RR Lyrae stars that could potentially be moving at hypervelocity.

Narrowing Down the True Runaways

The work did not stop there. Each candidate star’s light curve was examined in detail, and Doppler shifts were selected for the most reliable cases. This careful scrutiny reduced the sample further, yielding 87 RR Lyrae stars identified as the most trustworthy hypervelocity candidates. Among them, seven had tangential velocities exceeding 800 kilometers per second, placing them near or beyond the threshold of escape from the Milky Way.

When the researchers looked at where these stars were located, a pattern emerged. The stars fell into two distinct groups. One group was concentrated toward the Milky Way’s galactic center, while the other clustered around the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, two irregular dwarf galaxies that lie near the Milky Way.

Their locations and motions suggest dramatic origins. These stars appear to have reached hypervelocity status through the Hills mechanism or similar gravitational interactions. Many of them are moving fast enough to exceed the Milky Way’s escape velocity, meaning they were likely ejected from their original host systems and are now on paths that lead them out of the galaxy entirely.

Following the Trails Backward

Each of these stars carries a history written in its motion. By reconstructing their trajectories, astronomers can infer where the stars came from and what forces shaped their journeys. The clustering near the galactic center points to interactions with Sagittarius A*, while the association with the Magellanic Clouds hints at complex gravitational dynamics involving multiple galaxies.

The team believes that future observations will sharpen this picture. Continued data from the Gaia satellite, combined with detailed spectroscopic analysis, should help clarify the origins of these runaway stars and the precise mechanisms that launched them.

As more hypervelocity stars are identified and tracked, the Milky Way’s halo will come into sharper focus. The distribution of mass, both visible and dark, will be constrained by the paths of these stellar exiles.

Why These Escaping Stars Matter

This research matters because it turns some of the oldest stars in the galaxy into probes of its deepest secrets. By using RR Lyrae stars as tracers of hypervelocity motion, astronomers gain a new window into the Milky Way’s gravitational structure and its dark matter halo.

Dark matter remains one of the deepest mysteries in all of modern physics. It shapes galaxies, governs their motions, and yet reveals itself only through gravity. Hypervelocity stars, flung across the galaxy by extreme events, are among the few tools capable of mapping this invisible realm.

Beyond the technical insights, there is a profound narrative here. These stars are survivors of violent encounters, witnesses to the immense power of black holes and galactic forces. By listening to their steady pulses and tracking their frantic escape, astronomers are learning not just how the Milky Way is built, but how it evolves, interacts, and sometimes violently reshapes the lives of its stars.

In following the paths of stars that are leaving home forever, scientists are uncovering the hidden story of the galaxy they leave behind.

More information: Haozhu Fu et al, Search for Distant Hypervelocity Star Candidates Using RR Lyrae Stars, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae0c09