Deep in the cosmos, nearly ten billion light-years away, lies a blazing beacon of light known as 4FGL J0309.9-6058. To most of us, this name may sound like a string of random numbers—but to astronomers, it marks one of the most intriguing cosmic phenomena recently uncovered. Using NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, a team of researchers from Shanghai Normal University and their collaborators have discovered a mysterious, rhythmic pulse coming from this distant blazar. The finding, published on October 24 on the arXiv preprint server, adds a new piece to the cosmic puzzle of how supermassive black holes behave at the centers of distant galaxies.

What Exactly Is a Blazar?

To understand the significance of this discovery, one must first understand what a blazar is. A blazar is one of the brightest and most violent objects in the known universe. It sits at the heart of a galaxy, powered by a supermassive black hole millions or even billions of times more massive than the Sun.

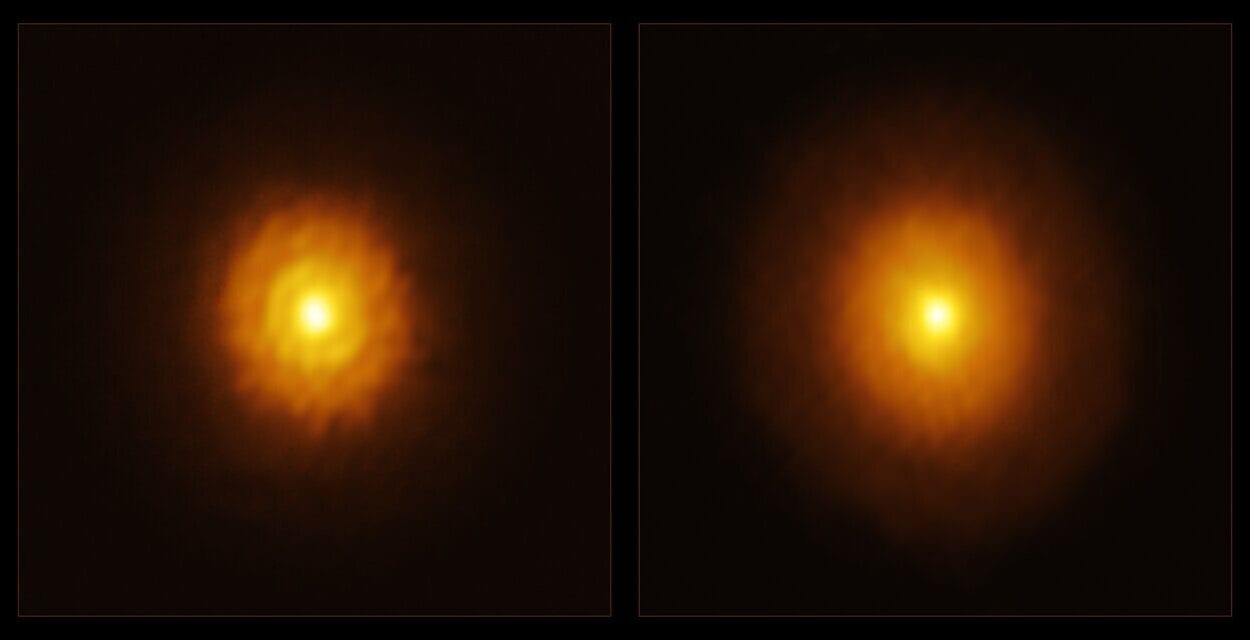

These cosmic monsters feed on surrounding gas and dust, pulling matter inward through a spinning disk known as an accretion disk. In the process, some of this infalling matter is flung outward at nearly the speed of light through gigantic jets of energy. When one of these jets happens to be aimed almost directly toward Earth, we see a blazar—a dazzling, flickering cosmic lighthouse visible across billions of light-years.

Blazars are a special type of active galactic nucleus (AGN)—galaxies with exceptionally bright centers powered by accreting black holes. Astronomers classify blazars into two main types: Flat-Spectrum Radio Quasars (FSRQs), which show broad and prominent emission lines in their optical spectra, and BL Lacertae objects (BL Lacs), which lack such features.

The blazar in this new study, 4FGL J0309.9-6058, also known as PKS 0308-611, belongs to the FSRQ class. It resides at a redshift of approximately 1.48, meaning the light we see today began its journey when the universe was less than half its current age.

The Pulse in the Darkness

Astronomers have long known that blazars are dynamic, with brightness that can change dramatically over days, weeks, or even years. But in some rare cases, their light shows a repeating rhythm—a quasi-periodic oscillation, or QPO. Detecting such a pattern is like finding a heartbeat in the light of a distant galaxy.

Led by Jingyu Wu of Shanghai Normal University, the research team analyzed years of data collected by the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which observes the universe in the high-energy range of 0.1–300 giga-electronvolts (GeV). The team searched for regular patterns in the gamma-ray emissions of 4FGL J0309.9-6058, using advanced statistical methods such as the Lomb-Scargle Periodogram, REDFIT, and the weighted wavelet Z-transform.

What they found was striking: a periodic signal repeating roughly every 550 days—about one and a half years—in the blazar’s gamma-ray emissions. This QPO was not a random fluctuation. Its significance level reached 3.72σ locally and 2.72σ globally—meaning the likelihood of it being a coincidence is quite low.

A Cosmic Time Lag

The team didn’t stop there. They compared the gamma-ray data with optical observations and found something even more intriguing: the optical light lagged behind the gamma rays by about 228 days. This delay suggests that the optical and gamma-ray emissions are not produced in the same region. Instead, they likely originate from separate zones along the blazar’s powerful jet—possibly at different distances from the central black hole.

This separation provides an important clue. If the gamma rays are emitted closer to the black hole and the optical light farther out, the time lag can tell scientists about the structure and motion of the jet itself.

Searching for the Source of the Oscillation

When faced with a cosmic rhythm like this, astronomers naturally ask: what could cause it?

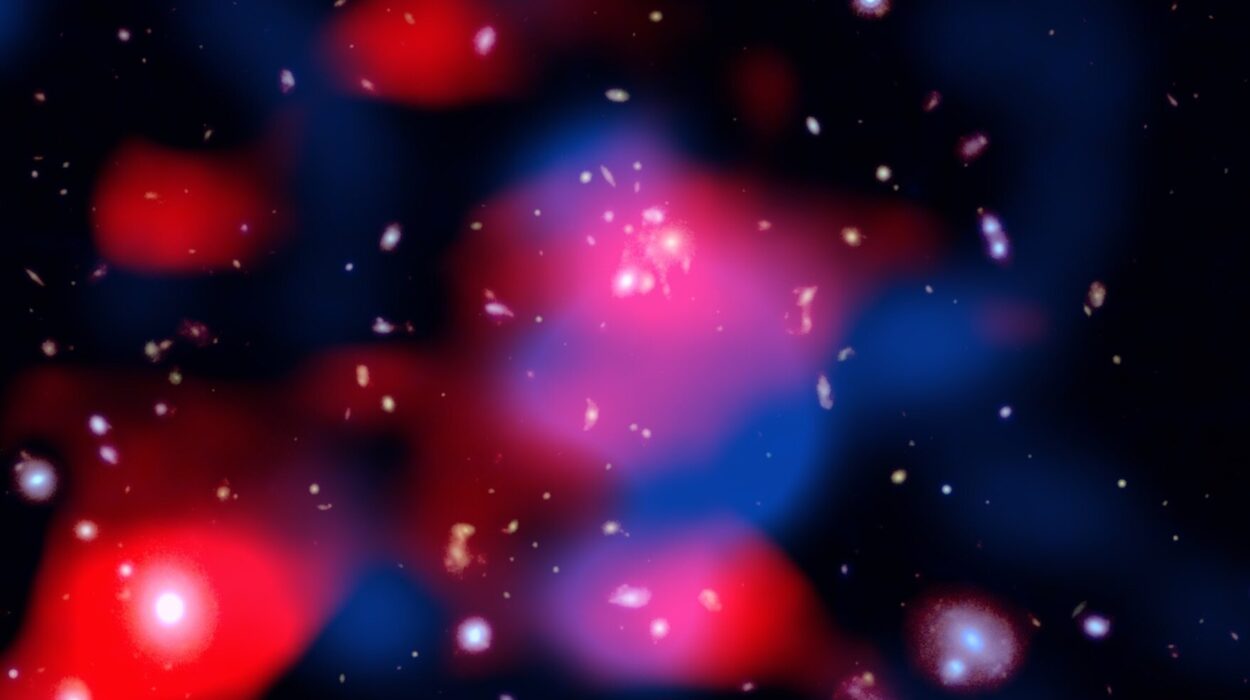

The team considered several possibilities. One hypothesis involves the presence of two supermassive black holes orbiting each other at the galaxy’s core. If 4FGL J0309.9-6058 hosts a binary black hole system, the orbital motion could create periodic changes in the accretion disk or the direction of the jet, leading to repeating variations in brightness.

However, the researchers found that this explanation did not fit the data perfectly. The timescale of the oscillation and the nature of the observed time lag suggested a different scenario—jet precession.

The Dance of a Precessing Jet

Imagine a spinning top that slowly wobbles as it turns—that wobble is called precession. A similar process can occur in blazars, where the jet of high-energy particles emitted from the black hole slowly changes direction over time. If the jet is precessing, the angle of its beam relative to Earth changes periodically, causing fluctuations in brightness as seen from our vantage point.

According to Wu and his team, jet precession offers the most plausible explanation for the 550-day oscillation in 4FGL J0309.9-6058. As the jet swings slightly toward and away from Earth, the observed gamma-ray intensity rises and falls rhythmically. The time lag between the optical and gamma-ray signals can be understood as the result of emissions being produced at different points along this precessing jet.

“The jet precession model emerges as the most promising explanation,” the researchers concluded. “The precessing jet generates QPO signals in both the optical and gamma-ray bands, and the observed time lag reveals the distance between these emission regions.”

Why This Discovery Matters

The identification of a QPO in 4FGL J0309.9-6058 is more than just another observation—it adds to a growing body of evidence that some blazars exhibit structured, periodic behavior rather than purely random variability. These cosmic rhythms could reveal the physical processes occurring near the event horizons of supermassive black holes, where gravity, magnetism, and relativity intertwine in extreme ways.

Detecting a QPO also provides a rare window into the geometry of a blazar’s jet. Understanding how these jets form, stabilize, and precess is crucial because they play a key role in shaping their host galaxies and influencing the intergalactic environment. Jets can carry enormous amounts of energy across vast distances, regulating star formation and redistributing matter across the cosmos.

Furthermore, the possibility that some blazars may harbor binary supermassive black holes is deeply significant. When two such giants spiral together, they are expected to produce powerful gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Observations of periodic signals in blazars could one day help identify systems on the verge of merging, offering indirect clues about where to look for these cosmic gravitational wave beacons.

The Human Side of Discovery

Behind every astronomical discovery lies human curiosity and perseverance. For the researchers, detecting a faint rhythmic signal buried in years of gamma-ray data required meticulous analysis and an unrelenting drive to find order in cosmic chaos.

Gamma rays, the universe’s most energetic form of light, are notoriously difficult to study. They cannot be detected by ground-based observatories because Earth’s atmosphere blocks them. NASA’s Fermi Telescope, orbiting above the planet since 2008, has opened a new window into this high-energy universe, revealing thousands of previously unknown sources.

For Jingyu Wu and the team, this finding is a reminder that even in a universe governed by seemingly chaotic processes, patterns can emerge—patterns that may tell stories of spinning black holes, dancing jets, and galaxies locked in eternal motion.

More information: Jingyu Wu et al, Detection of Quasi-periodic Oscillations in the γ-Ray Light Curve of 4FGL J0309.9-6058, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.21205