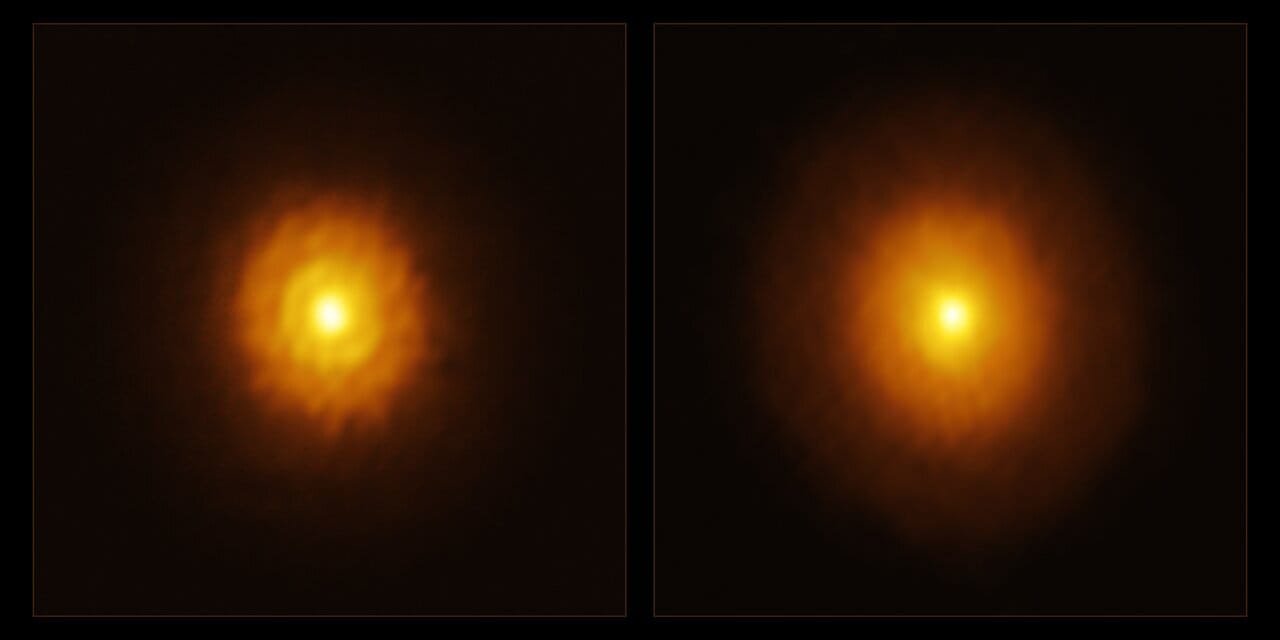

For a long time, the star MP Mus seemed like just another adolescent sun in the cosmos, cradled in a disk of cosmic dust and gas yet apparently alone, its surroundings eerily smooth and featureless. Astronomers had peered at it, searching for signs of planets coalescing in its swirling disk, and found… nothing. No gaps, no rings, no clues. Just an unbroken pancake of cosmic dust.

But the universe, as it so often does, had secrets hiding beneath the surface. And thanks to a daring second look—with sharper eyes and deeper tools—astronomers have now discovered that MP Mus was never alone at all.

In an extraordinary breakthrough, an international team led by the University of Cambridge has uncovered a giant exoplanet, anywhere from three to ten times the mass of Jupiter, hiding within MP Mus’s protoplanetary disk. Their findings, published in Nature Astronomy, mark the first time the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission has helped discover a planet still forming inside a dusty stellar nursery.

A Cosmic Nursery Cloaked in Mystery

MP Mus, also known as PDS 66, sits about 360 light-years away in the constellation Musca. Astronomers believe it’s between seven and ten million years old—practically a newborn by cosmic standards. Stars of this age are often wrapped in protoplanetary disks, vast clouds of gas and dust where the seeds of future planets swirl, collide, and eventually grow into new worlds.

Scientists study these disks not only to understand the stars themselves but to glimpse the early chapters of planetary systems—including clues to how our own solar system was born.

But detecting planets within these disks is notoriously difficult. The swirling dust obscures the view, and any forming planets are tiny compared to the massive disks that surround them. So far, only three young planets have been conclusively spotted hiding inside their dusty cradles.

Dr. Álvaro Ribas, of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, is one of the astronomers who’s made a career out of studying these elusive disks. “We first observed this star at the time when we learned that most disks have rings and gaps, and I was hoping to find features around MP Mus that could hint at the presence of a planet or planets,” he said.

Back in 2023, Ribas used the powerful Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile to peer into MP Mus’s disk. The result was disappointing: a smooth, featureless swirl of dust with no telltale gaps or structures that might signal a hidden planet carving its way through the cosmic dough.

“Our earlier observations showed a boring, flat disk,” Ribas recalled. “But this seemed odd to us, since the disk is between seven and ten million years old. In a disk of that age, we would expect to see some evidence of planet formation.”

A Star’s Subtle Dance

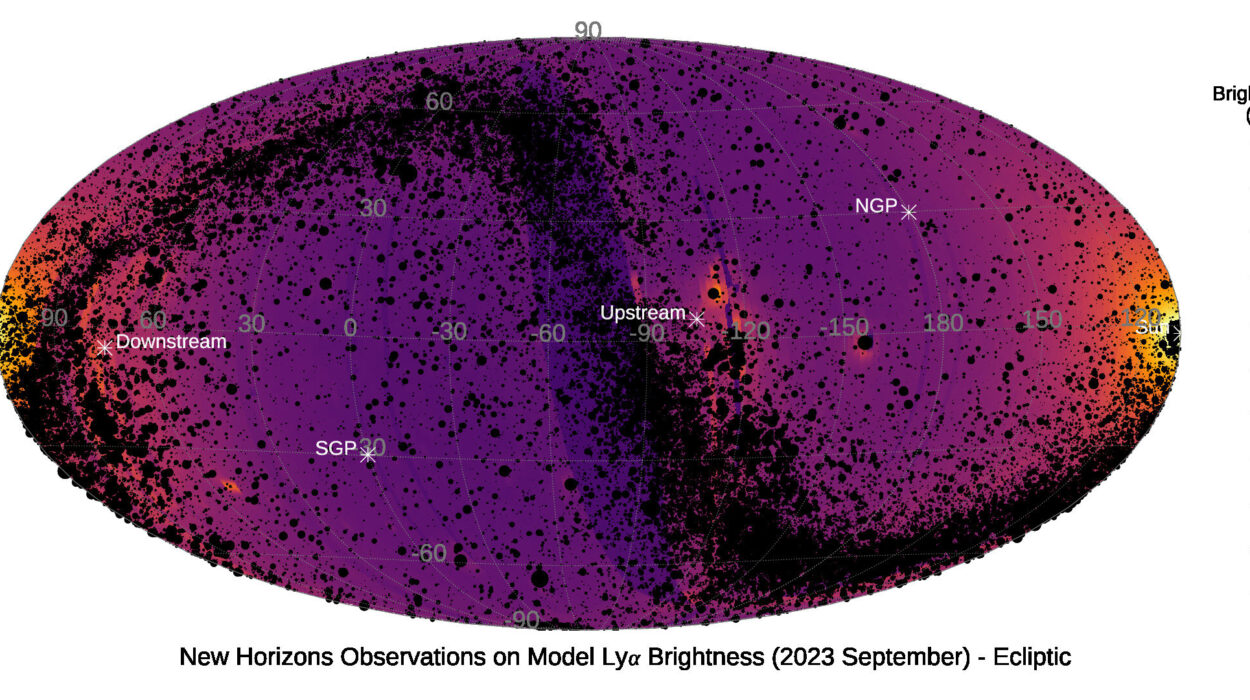

Meanwhile, across Europe, astronomer Miguel Vioque was examining data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft, which precisely maps the positions and movements of over a billion stars. While studying MP Mus, Vioque noticed something peculiar: the star appeared to be gently wobbling.

At first, he assumed there was a mistake in his calculations. After all, MP Mus was known to have a featureless disk and no planets. But then he happened to catch a talk by Ribas, who revealed preliminary evidence of an inner cavity in MP Mus’s disk. That gap hinted at the gravitational influence of something big—and invisible.

“I was revising my calculations when I saw Álvaro give a talk presenting preliminary results of a newly-discovered inner cavity in the disk, which meant the wobbling I was detecting was real and had a good chance of being caused by a forming planet,” said Vioque.

A New Look, a New Discovery

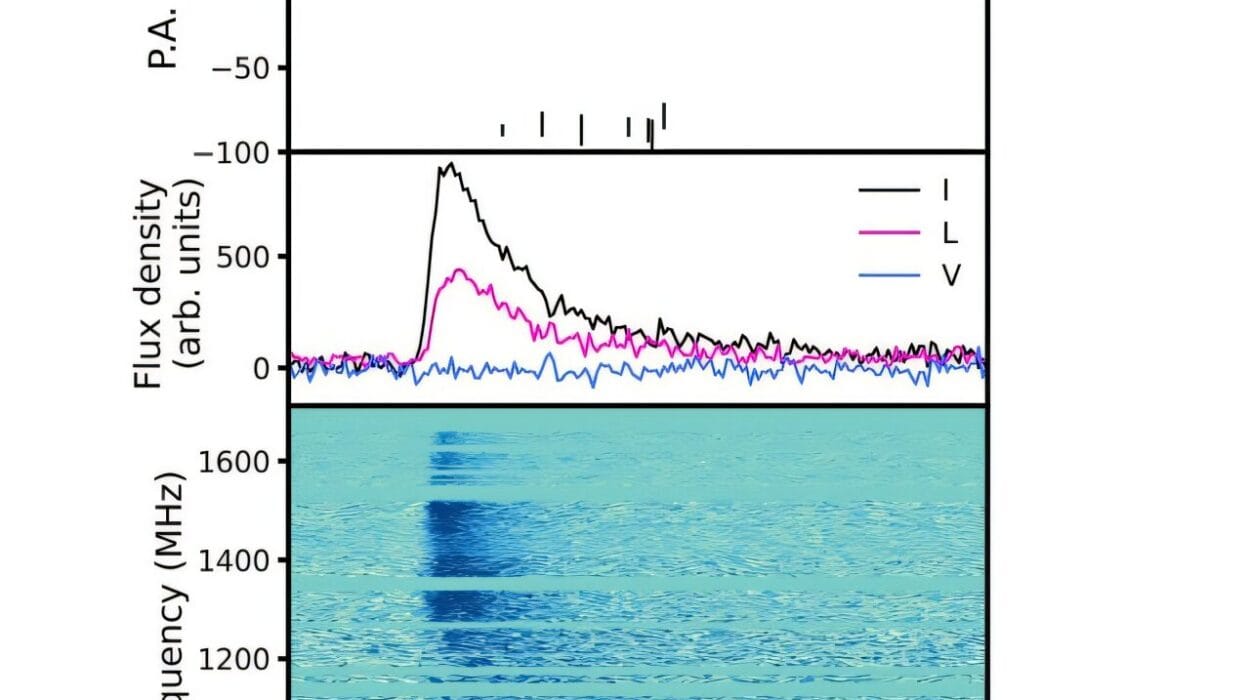

Armed with this intriguing clue, Ribas and his colleagues went back to ALMA for a deeper look. This time, they observed MP Mus at a longer wavelength—3 millimeters instead of the shorter wavelengths used before. Longer wavelengths allow astronomers to see through thicker dust, probing deeper into the disk’s hidden layers.

The payoff was immediate. The new images revealed what had been hidden all along: a cavity near the star and two additional gaps farther out in the disk. These features are cosmic fingerprints left by young planets as they plow through the disk, sweeping up dust and gas and leaving behind visible grooves—like tracks in fresh snow.

The combination of Gaia’s evidence of stellar wobble and ALMA’s newly discovered cavities pointed to a single conclusion: MP Mus was playing host to a giant, unseen planet.

“Our modeling work showed that if you put a giant planet inside the new-found cavity, you can also explain the Gaia signal,” Ribas explained. “And using the longer ALMA wavelengths allowed us to see structures we couldn’t see before.”

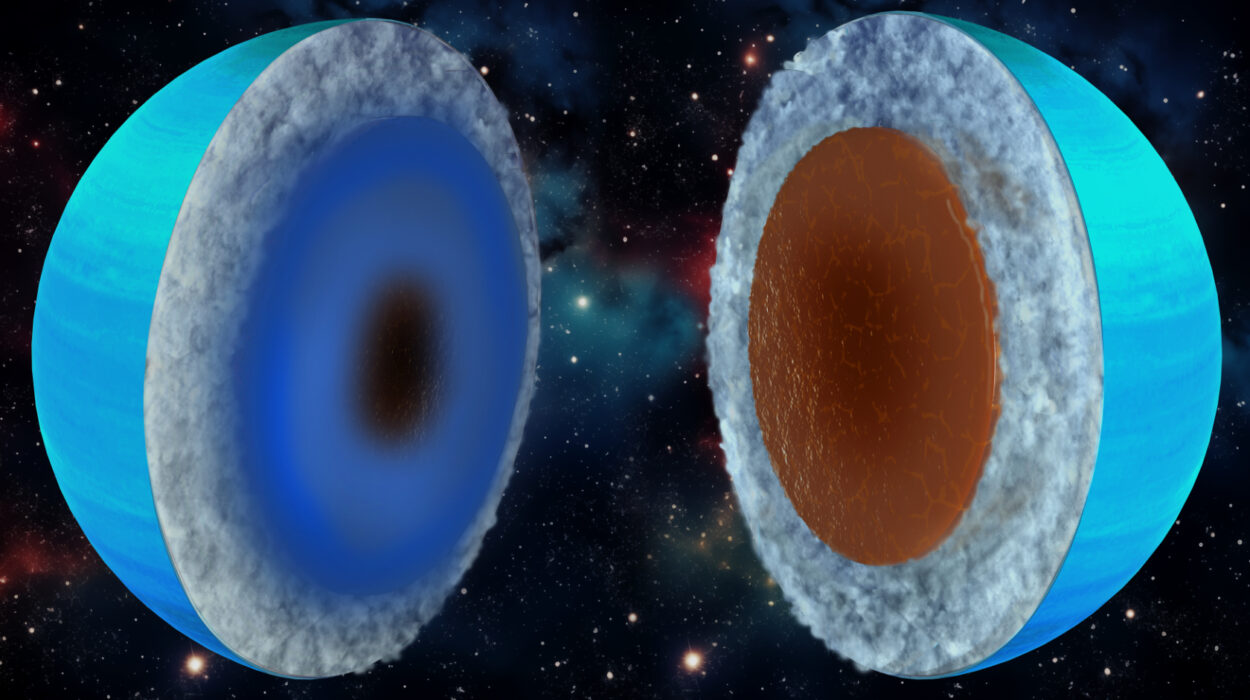

The planet, according to their models, likely weighs less than ten times the mass of Jupiter and orbits the star at a distance roughly one to three times that between Earth and the sun. It’s a behemoth in the making, swirling inside the dust and gas that might one day become a planetary system.

A New Era for Planet Hunting

This discovery marks the first time an exoplanet still forming inside a protoplanetary disk has been detected by combining Gaia’s measurements of stellar movements with ALMA’s high-resolution observations.

It’s a powerful demonstration of how modern astronomy often requires a cosmic team effort. Alone, neither Gaia nor ALMA could have revealed the planet lurking in MP Mus’s disk. Together, they’ve unlocked a hidden chapter in the story of planet formation.

“We think this might be one of the reasons why it’s hard to detect young planets in protoplanetary disks,” Ribas said. “In this case, we needed the ALMA and Gaia data together. The longer ALMA wavelength is incredibly useful, but to observe at this wavelength requires more time on the telescope.”

The implications go far beyond MP Mus. If astronomers can use this method to detect young planets hiding in other disks, it could dramatically expand our understanding of how planetary systems—including our own—are born and evolve.

Looking Deeper Into the Cosmic Cradle

In the coming years, new telescopes and upgrades to ALMA could help astronomers peer even deeper into these cosmic nurseries. The next-generation Very Large Array (ngVLA), for example, promises even higher sensitivity and resolution at millimeter wavelengths, potentially revealing countless other baby planets still cloaked in dust.

For now, MP Mus serves as a stunning reminder that even when the universe seems quiet and featureless, there’s often something extraordinary waiting to be discovered.

From a “boring, flat disk” to a hidden giant planet, the story of MP Mus shows how far we’ve come—and how much more the cosmos still has to reveal.

Reference: A young gas giant and hidden substructures in a protoplanetary disc, Nature Astronomy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02576-w