In the deep, silent infancy of the cosmos, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, the universe was a dark and cold expanse. This era, known as the cosmic dawn, was the stage for a transformation that would set the course for everything we see today. Within the centers of dark matter microhalos, vast reservoirs of invisible material, the first whispers of structure began to stir. Clouds of molecular hydrogen and helium drifted through the void, eventually cooling enough to succumb to the relentless pull of gravity. As these clouds collapsed, they didn’t just ignite with the nuclear fire we associate with modern suns. Instead, they tapped into a mysterious power source that has puzzled astronomers for decades: dark matter annihilation.

The Giants Powered by Shadows

These primordial titans, known as dark stars, were unlike any celestial body in the modern sky. While they were composed mostly of normal matter like hydrogen, they were fueled by the energy released when dark matter particles collided and destroyed one another within the star’s core. This unique engine allowed them to grow to staggering proportions, far exceeding the mass of the stars that form in our local neighborhood today. According to a recent study led by Cosmin Ilie and a team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, the Space Telescope Science Institute, and the University of Texas at Austin, these supermassive objects are not just theoretical curiosities. They may be the “missing link” required to explain a series of baffling discoveries made by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

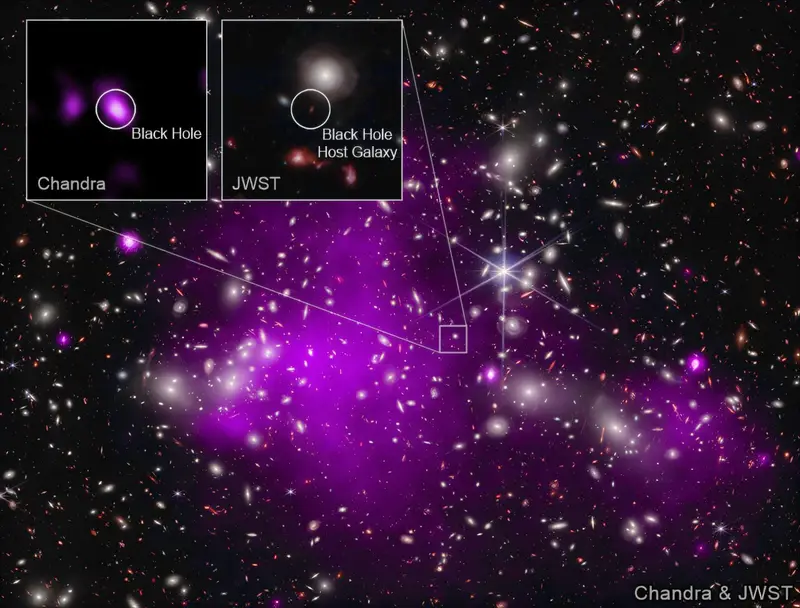

For years, the standard models of galaxy formation suggested a slow, methodical buildup of cosmic structures. However, when JWST turned its powerful golden eye toward the most distant reaches of space, it found a reality that defied every simulation. The telescope captured images of objects that shouldn’t exist according to the old rules: galaxies that were too bright, black holes that were too heavy, and strange pinpricks of light that didn’t fit any known category. The team’s research, published in the journal Universe, suggests that the “features” of dark star theory are the exact solutions needed to solve these three pressing cosmic puzzles.

Monsters in the Deep Blue

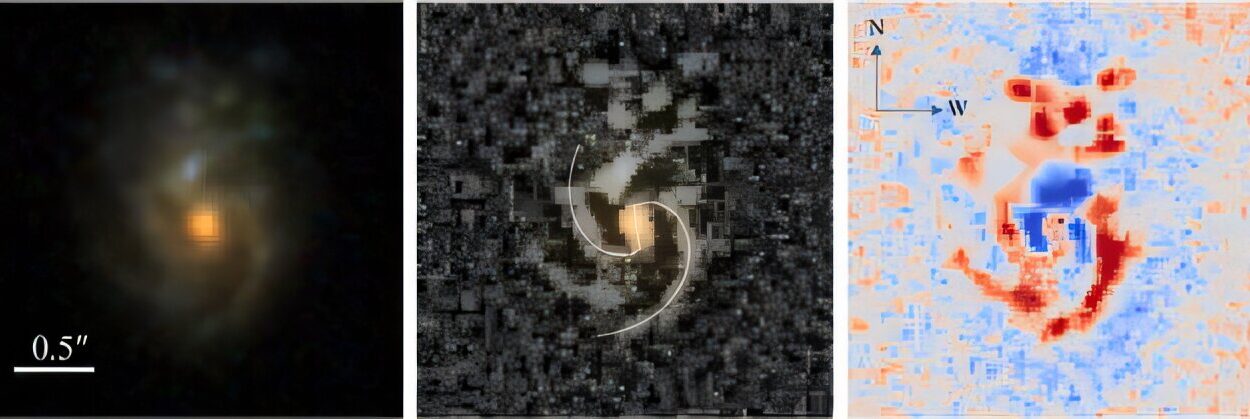

The first of these puzzles involves a class of objects astronomers have nicknamed blue monsters. These are extremely distant galaxies that appear incredibly bright yet remain ultra-compact and almost entirely devoid of dust. In the pre-JWST era, no theoretical model predicted that such concentrated bursts of luminosity could exist so early in time. They are the overachievers of the early universe, packing the brightness of entire galaxies into tiny, efficient spaces.

The researchers propose that dark stars are the secret behind this intense glow. Because these stars can become supermassive, they provide a natural explanation for the extreme brightness observed in these compact regions. Instead of needing billions of small, conventional stars to form all at once—a process that is difficult to justify in the early universe—a few massive, dark-matter-powered giants could provide the necessary light. These blue monsters are essentially the footprints of a time when the universe was much more energetic and efficient at creating light than anyone had previously imagined.

The Mystery of the Little Red Dots

As if the blue monsters weren’t strange enough, JWST also revealed a new class of objects that look like tiny, crimson stains against the blackness of space: the little red dots (LRDs). These sources are as compact as the blue monsters and similarly dustless, yet they pose a unique contradiction. In the standard view of the universe, such red objects are usually thought to be galaxies shrouded in dust or powered by active black holes. However, these little red dots emit unexpectedly little to no X-ray radiation, which is usually the “smoking gun” of a ravenous, growing black hole.

This lack of X-ray signatures has left scientists scratching their heads, but dark star theory offers a seamless fit. Because dark stars are powered by annihilation rather than the chaotic accretion of matter into a black hole, they can shine brightly in infrared and visible light (appearing red due to their distance and redshift) without producing the high-energy X-rays that a black hole would. They are calm, massive beacons of light that mimic the appearance of a galaxy or a quasar without the violent X-ray output, effectively filling the “identity gap” for these mysterious red dots.

Seeds of the Great Abyss

The third puzzle involves the sheer scale of the universe’s most terrifying residents: supermassive black holes (SMBHs). Observations of distant quasars have shown that even in the very early universe, black holes had already grown to millions or billions of times the mass of our sun. This is a chronological nightmare for astronomers; there simply wasn’t enough time for a “normal” star to live, die, and then grow into such a behemoth by swallowing gas.

The study argues that dark stars are the natural seeds for these giants. Because a dark star can grow to be supermassive itself, it doesn’t need to wait billions of years to accumulate mass. When the dark matter fuel eventually runs out, the entire massive structure would collapse directly into a black hole. This gives the universe a “head start,” placing overmassive black hole galaxies on the fast track to growth. This mechanism elegantly explains why we see such mature, heavy black holes in a universe that was supposedly still in its “toddler” phase.

A Fingerprint in the Light

While the idea of stars powered by invisible matter sounds like science fiction, the researchers are finding tangible evidence in the data. They performed a sophisticated spectroscopic analysis of specific targets identified by JWST, such as the objects JADES-GS-13-0 and JADES-GS-14-0. By breaking down the light from these sources, they looked for a “smoking gun”—a specific signature that only a dark star would leave behind.

They found evidence for absorption features due to helium in the spectra of these distant sources. These specific patterns of light absorption are consistent with the predicted atmosphere and temperature of a supermassive dark star. This finding builds upon previous studies from 2023 and 2025 that identified photometric and spectroscopic candidates, moving the theory from a mathematical possibility toward an observed reality. Each new piece of data from JWST seems to reinforce the idea that the first stars were not the small, flickering candles we expected, but rather massive, dark-matter-fueled furnaces.

Why the Cosmic Dawn Matters

Understanding these ancient objects is about more than just solving astronomical riddles; it is a quest to understand the fundamental building blocks of our reality. Dark matter makes up the vast majority of the matter in the universe, yet it remains one of the greatest mysteries in modern science. It does not emit light, and we cannot touch it. However, if dark stars truly exist, they act as cosmic laboratories that reveal the secrets of this invisible substance.

By studying how these stars form and shine, scientists can determine the physical properties of the dark matter particle. This celestial investigation complements the work being done in high-tech laboratories on Earth, where researchers use massive detectors to try and catch a single dark matter particle in the act of direct detection. While Earth-bound experiments look for dark matter in the here and now, JWST is looking back through time to see how dark matter shaped the very first light in the cosmos. If these theories continue to hold, the dark star will be remembered as the bridge that allowed the universe to cross from the total darkness of the Big Bang to the star-filled sky we marvel at today.

Study Details

Cosmin Ilie et al, Supermassive Dark Stars and Their Remnants as a Possible Solution to Three Recent Cosmic Dawn Puzzles, Universe (2025). DOI: 10.3390/universe12010001