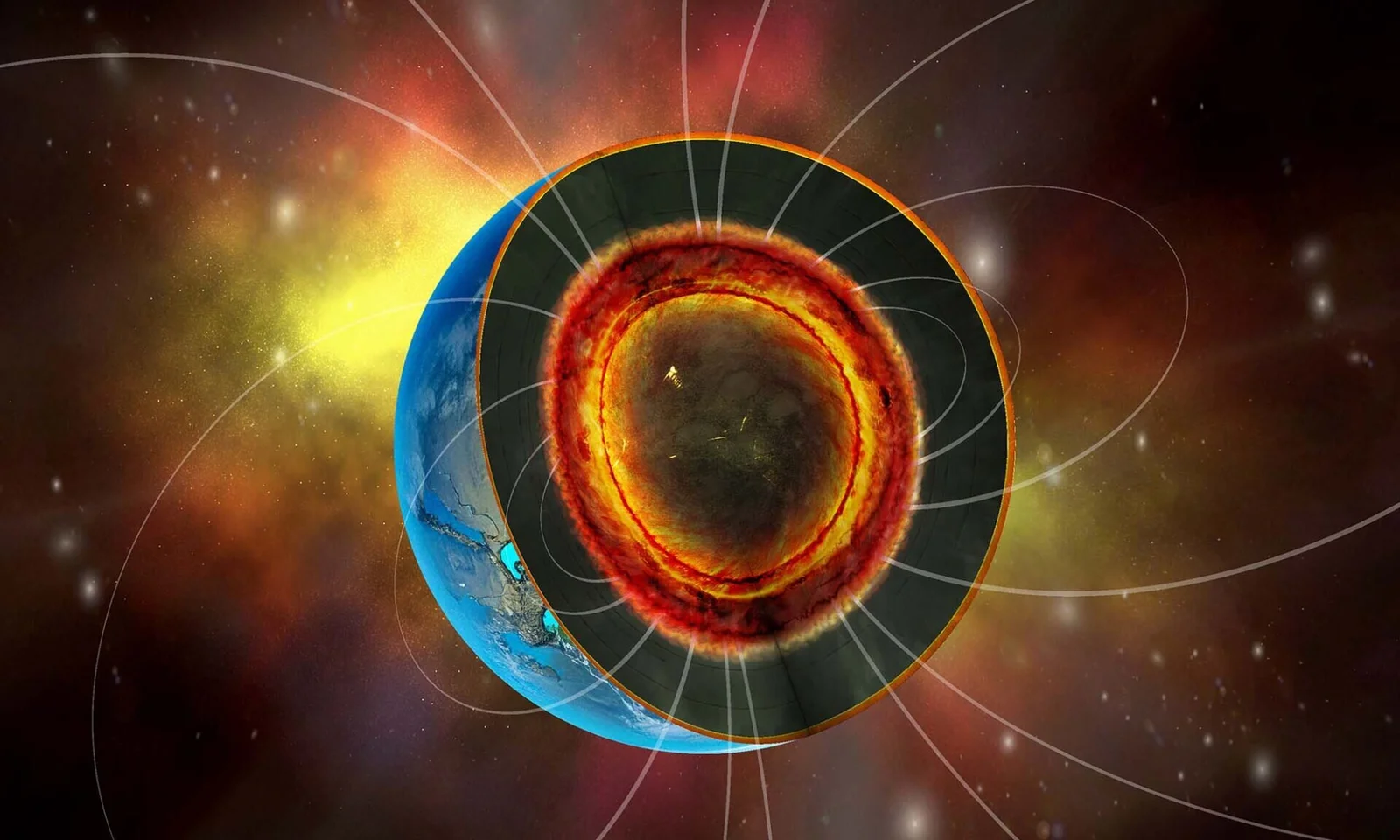

Far beneath the imagined landscapes of distant worlds, beyond mountains no telescope can see and depths no probe has reached, something vast and restless may be flowing. On certain alien planets known as super-Earths, scientists now believe there could be enormous oceans of molten rock buried deep inside—oceans not of water, but of glowing, liquid stone. And these hidden seas may be doing something astonishing: generating powerful magnetic fields capable of shielding entire planets from deadly cosmic radiation.

This idea reshapes a long-standing assumption about what it takes for a planet to protect itself—and possibly host life. For decades, Earth’s own magnetic field has been the gold standard, born from the churning motion of molten iron in our planet’s outer core. But what if some worlds achieve this vital protection in a completely different way?

When Planetary Hearts Refuse to Behave

On Earth, the story of magnetism begins in the core. Heat and motion in the planet’s liquid iron outer layer drive a process called a dynamo, which creates the magnetic field that deflects high-energy particles from space. Without it, Earth’s surface would be far more hostile to life.

Yet when scientists look at other rocky planets, the picture becomes complicated. Venus and Mars, for example, lack strong global magnetic fields today. Their cores do not have the right physical conditions to sustain the same kind of dynamo Earth enjoys. This raises a troubling question for worlds beyond our solar system, especially those larger than Earth. Many super-Earths may have cores that are solid or fully liquid in ways that prevent traditional core dynamos from forming at all.

If their cores cannot do the job, where could a protective magnetic field come from?

Super-Earths: Familiar, Yet Entirely Strange

Despite the name, super-Earths are not simply larger versions of our home planet. The term refers only to their size and mass, placing them between Earth and ice giants like Neptune. Scientists believe many of them are primarily rocky, with solid surfaces rather than thick blankets of gas.

What makes super-Earths especially intriguing is how common they appear to be. They are the most frequently detected type of exoplanet in our galaxy, even though none exist in our own solar system. Many orbit within their stars’ habitable zones, where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist. Their abundance turns them into a natural laboratory for understanding how planets form, evolve, and possibly become friendly to life.

But habitability is more than temperature and water. Without protection from radiation and stellar winds, a planet’s atmosphere can erode, and its surface can become biologically unforgiving. That protection often comes from magnetism.

A Forgotten Chapter in Earth’s Own Past

The key to this mystery may lie in a dramatic phase of Earth’s early history. Scientists believe that shortly after Earth formed, it possessed something called a basal magma ocean, or BMO. This was a deep layer of partially or fully molten rock sitting at the base of the planet’s mantle, just above the core.

This molten layer did not last forever on Earth. Over time, as the planet cooled, it solidified. But its existence may have played a crucial role in shaping Earth’s early magnetic field, heat flow, and chemical evolution.

Now imagine scaling that scenario up. Super-Earths are larger than Earth and experience far higher internal pressures. Those conditions make it much more likely that a BMO could persist for billions of years instead of fading away. That persistence changes everything.

Recreating Alien Depths on Earth

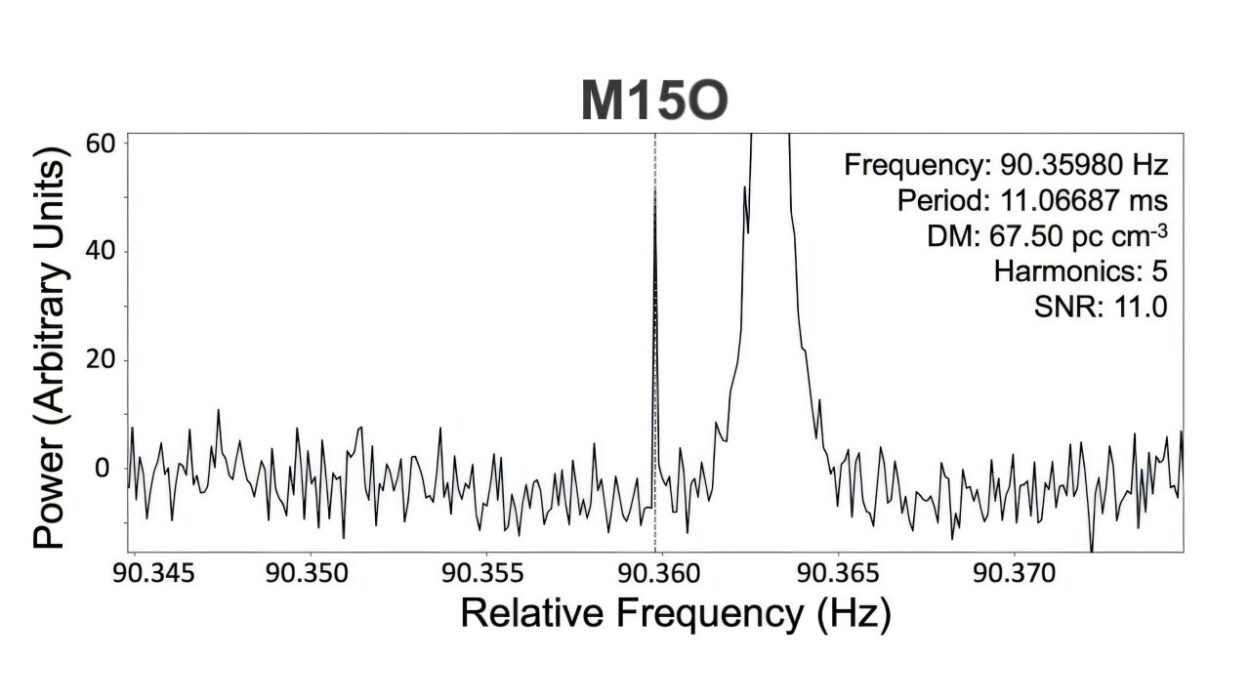

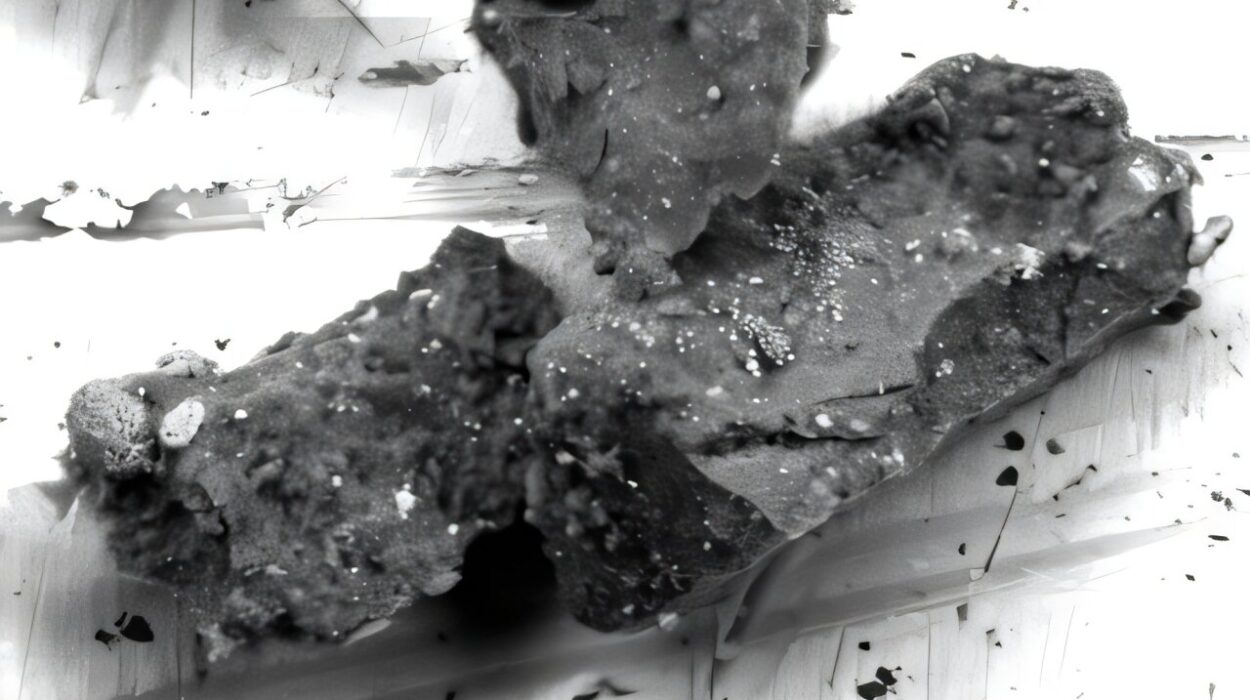

To test whether a deep ocean of molten rock could actually generate a magnetic field, researchers needed to simulate conditions far beyond anything found naturally on Earth’s surface. In a study published in Nature Astronomy, a team from the University of Rochester, led in part by Miki Nakajima, turned to an unusual combination of tools.

At the university’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics, the researchers used laser shock experiments to reproduce the crushing pressures expected deep inside super-Earths. These experiments were paired with quantum mechanical simulations and planetary evolution models, allowing the team to explore how molten rock behaves under extreme conditions.

Their focus was simple but bold: determine whether molten rock in a basal magma ocean could become electrically conductive enough to drive a dynamo.

When Molten Rock Learns to Carry a Current

Under everyday conditions, molten rock is not a great conductor of electricity. But the experiments revealed something remarkable. At the immense pressures found deep within super-Earths, deep-mantle molten rock becomes electrically conductive.

Conductivity is the missing ingredient. Once molten rock can carry electrical currents, its movement can generate a magnetic field, much like the flow of liquid iron in Earth’s core. The researchers found that this process could sustain a powerful magnetic field for billions of years.

For super-Earths more than three to six times the size of Earth, these BMO dynamos—driven not by metal, but by molten rock—could produce magnetic fields even stronger and longer-lasting than Earth’s own.

This finding opens a new chapter in planetary science. Magnetism, it seems, does not belong exclusively to iron cores.

A New Path to Planetary Protection

Magnetic fields act as invisible shields. They deflect dangerous cosmic radiation and high-energy particles that can strip away atmospheres and damage organic molecules. Without them, planets are exposed to the harshness of space.

Nakajima emphasizes how central this protection is. “A strong magnetic field is very important for life on a planet,” she explains. While many terrestrial planets lack the right core conditions to generate such fields, super-Earths may have another option. They can produce dynamos in their core and/or magma, increasing their potential habitability.

The idea that molten rock alone could safeguard a planet expands the range of worlds scientists might consider life-friendly. Planets once dismissed because their cores seemed unsuitable may deserve a second look.

Science at the Edge of Disciplines

This discovery did not come easily. For Nakajima, whose background is primarily computational, stepping into experimental work posed both excitement and challenge. The project demanded collaboration across research fields, blending theory, simulation, and high-energy laboratory experiments into a single coherent picture.

That interdisciplinary effort mirrors the complexity of the planets themselves. Understanding super-Earths requires thinking beyond familiar Earth-based assumptions and embracing the strange physics of worlds shaped by extreme pressure and heat.

Nakajima looks ahead with anticipation, eager for future observations. Detecting magnetic fields around distant exoplanets could provide a direct test of the team’s hypothesis and reveal whether molten rock dynamos are truly at work across the galaxy.

Why This Discovery Matters

This research matters because it changes how scientists define a potentially habitable planet. Magnetic fields are not a luxury; they are a form of planetary armor. By showing that basal magma oceans can generate long-lasting magnetic fields, the study expands the number of worlds that might be able to protect their atmospheres and surfaces.

Super-Earths are everywhere in our galaxy. If many of them harbor deep oceans of molten rock capable of producing magnetic shields, then the conditions needed for life may be more common than once thought. Habitability may not hinge on having an Earth-like core alone, but on the dynamic, glowing depths hidden far below a planet’s surface.

In the end, this work invites a humbling realization. Life-friendly worlds may not always resemble Earth on the inside. Some may owe their protection to silent, fiery oceans of rock, endlessly flowing in darkness, shaping the fate of entire planets without ever seeing the light of a star.

Study Details

Miki Nakajima et al, Electrical conductivities of (Mg,Fe)O at extreme pressures and implications for planetary magma oceans, Nature Astronomy (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02729-x