Long before Earth existed, before the Sun had fully taken shape, the universe was still learning how to shine. Galaxies were young and fragile, stars lived fast and died violently, and light itself was only beginning to travel freely through space. From that distant era, a brief and powerful flash has now reached us. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have uncovered a supernova so ancient that it exploded when the universe was only 1 billion years old. They named it SN Eos, after the Greek goddess of the dawn, and the name could not be more fitting.

The discovery was reported on January 7 on the arXiv pre-print server, marking a rare moment when modern technology opens a direct window into the universe’s earliest chapters. This was not just another stellar explosion. It was a message from a time when the cosmos itself was still waking up.

When Stars End, Stories Begin

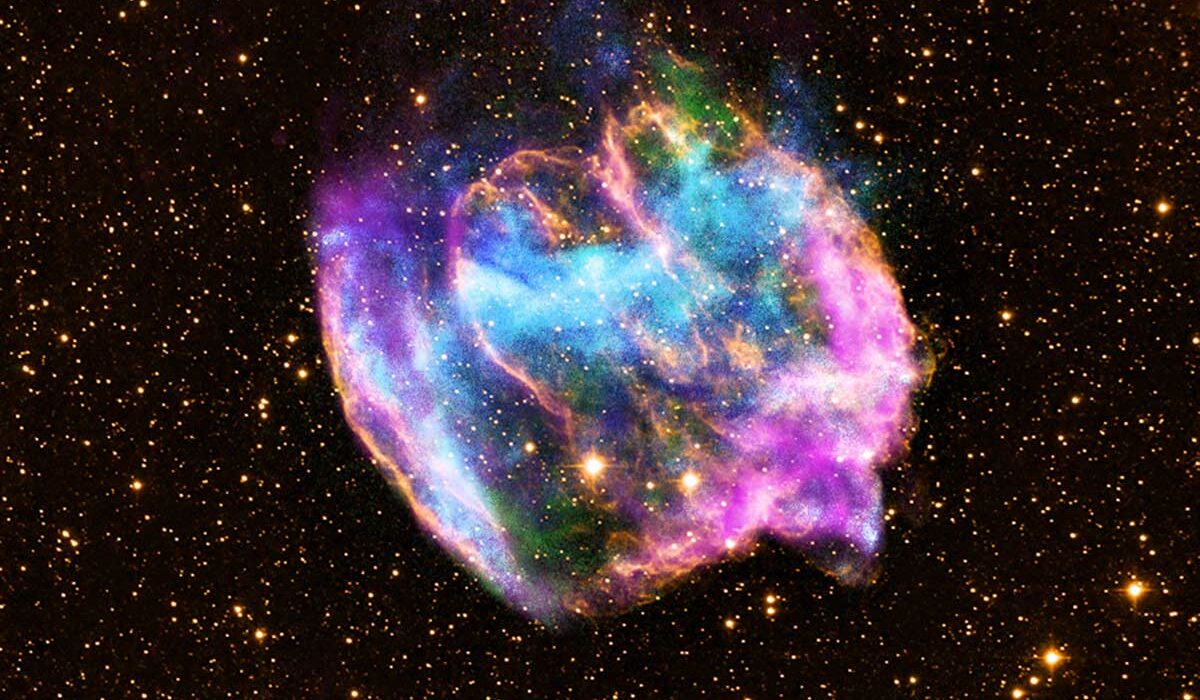

A supernova is the dramatic death of a star, an explosion so luminous it can briefly outshine entire galaxies. To astronomers, these events are far more than spectacles. They are records of stellar lives, encoded in light. By studying them, scientists learn how stars evolve, how galaxies grow, and how the universe changes over time.

Supernovae fall into two main families based on what their light reveals. Type I supernovae show no hydrogen in their spectra, while Type II supernovae clearly display hydrogen lines. That difference tells a crucial story about what kind of star exploded and how it died.

Type II supernovae are born from massive stars, those with more than 8 solar masses, that collapse under their own gravity. In a violent final act, their cores fall inward and rebound outward, tearing the star apart. These explosions, known as core-collapse supernovae, allow astronomers to study the very last moments of massive stars. When they occur in the early universe, they become especially valuable, offering rare clues about how the first generations of stars lived and died.

Seeing the Unseeable With Cosmic Magnification

Detecting a supernova from such an early era is not easy. Normally, these explosions would be far too faint to see across such unimaginable distances. But nature provided a helping hand.

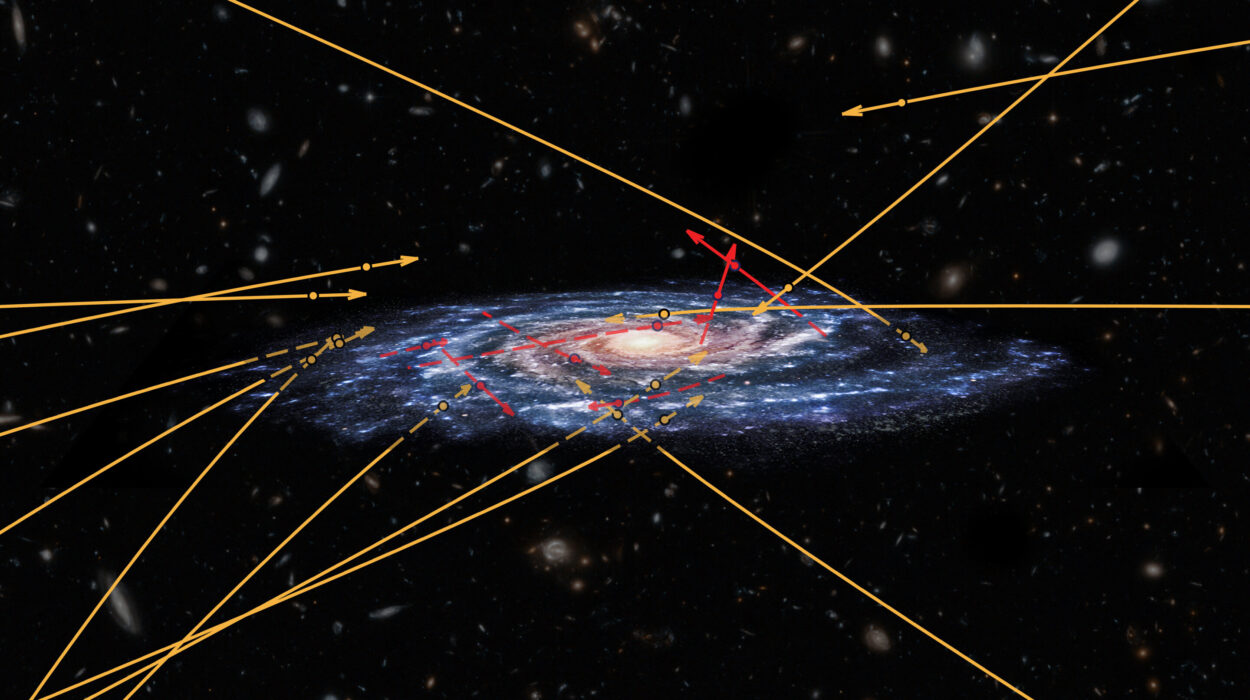

The team, led by David A. Coulter of Johns Hopkins University, relied on gravitational lensing, a phenomenon predicted by Einstein’s theory of gravity. Massive objects, like galaxy clusters, bend and magnify the light of objects behind them. This cosmic magnifying glass can make the invisible visible.

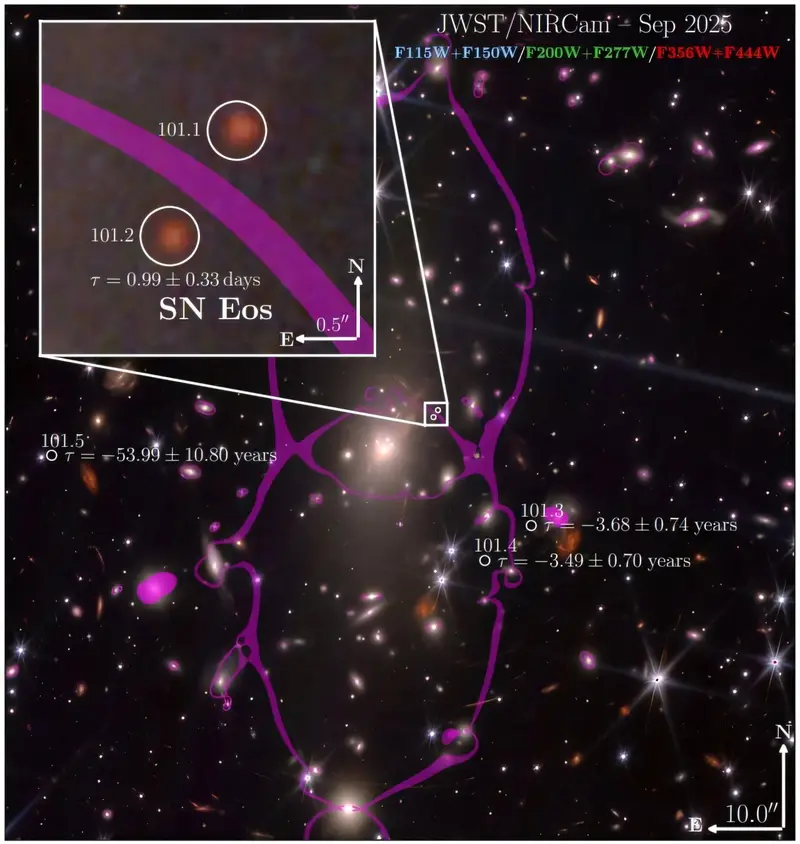

Using this method, the researchers observed a supernova appearing not once, but multiple times. Its light was split into magnified images by the gravity of the MACS 1931.8-2635 galaxy cluster. The discovery came from JWST/NIRCam imaging as part of the VENUS observations.

As the researchers wrote, “SN Eos” appeared as “a pair of images observed on September 1, 2025.” Without gravitational lensing, this ancient explosion would have remained hidden forever.

The Farthest Confirmed Supernova Ever Found

SN Eos is extraordinary not only because of its age, but because of how confidently it has been identified. It has a spectroscopic redshift of 5.133, placing it at an extreme distance. This measurement confirms that SN Eos is the farthest spectroscopically confirmed supernova ever discovered.

The supernova is embedded within a very faint Lyman-alpha emitting galaxy, a type of galaxy commonly associated with the early universe. These galaxies are dim, delicate, and difficult to study, making the presence of a supernova within one even more remarkable.

Each photon captured by JWST traveled for billions of years to reach its detectors. By the time that light arrived, the star that exploded was long gone, its host galaxy transformed by cosmic evolution. Yet the story of its death remained preserved in the light itself.

An Explosion After Cosmic Darkness Lifted

The timing of SN Eos’s explosion places it at a pivotal moment in cosmic history. The data indicate that it erupted shortly after the universe reionized and became transparent to ultraviolet radiation. Before this period, much of the universe was shrouded in neutral gas that absorbed energetic light. After reionization, light could finally travel freely across vast distances.

This makes SN Eos a rare witness to a newly illuminated universe. Its explosion occurred in an environment with a metal concentration below 10% of the solar abundance. In astronomy, metals are elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, and low metal content is a hallmark of early cosmic environments. Stars forming at that time were made from relatively pristine material, shaped by only a few earlier generations of stellar deaths.

Ultraviolet Light From a Dying Giant

One of the most intriguing aspects of SN Eos lies in its ultraviolet behavior. In its rest-frame, the supernova showed variable, bright, and rising far-ultraviolet emission. This kind of light carries important information about the temperature and structure of the exploding star.

By analyzing this emission, the team concluded that SN Eos was a Type IIP supernova, observed near the end of its plateau phase. Type IIP supernovae are known for maintaining a roughly constant brightness for an extended period after reaching their peak. This plateau occurs as energy from the explosion works its way through the star’s hydrogen-rich outer layers.

Seeing this familiar behavior in such an ancient supernova is striking. It suggests that, even in the early universe, massive stars could live and die in ways that resemble those seen much closer to home.

A Supernova Shaped by Scarcity

The researchers describe SN Eos as strongly lensed, multiply-imaged, and extremely metal-poor. Each of these characteristics adds another layer to its scientific value.

Its low metal content points to a time when the universe had not yet been enriched by many generations of stellar explosions. The elements that make planets, life, and even astronomers themselves were still being forged. SN Eos represents a step in that long chain of creation.

Because it is multiply imaged, astronomers can study the same explosion from slightly different paths through space. This provides a richer dataset and helps confirm the supernova’s properties with greater confidence.

Why This Discovery Matters

SN Eos is more than a distant explosion. It is a proof of concept and a promise. Its discovery underscores the core mission objectives of the James Webb Space Telescope, which include understanding the lives and deaths of the first stars, the origins of the elements, and the assembly and evolution of the youngest galaxies.

By confirming that Type II-Plateau supernovae existed in the early universe, SN Eos helps constrain models of early stellar evolution. It shows that massive stars were already forming, living, and dying in predictable ways when the universe was still young.

Most importantly, SN Eos reminds us that the universe keeps its memories in light. With tools like JWST and natural lenses formed by gravity, astronomers can now read those memories across billions of years. Each discovery like this brings us closer to understanding not just how stars die, but how everything we know began.

Study Details

David A. Coulter et al, A spectroscopically confirmed, strongly lensed, metal-poor Type II supernova at z = 5.13, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2601.04156