For decades, the windswept landscape of ‘Ubeidiya in the Jordan Valley has held its secrets in silence. Beneath layers of ancient sediment, beside fossil bones and shaped stones, lies a chapter of human history that researchers have long tried to read clearly. Now, a new study has pushed the story back further than many expected, revealing that this remarkable site likely dates to at least 1.9 million years ago.

That number changes everything.

For years, most scholars believed the site was between 1.2 and 1.6 million years old, a respectable age, but not extraordinary in the grand sweep of human evolution. Those earlier estimates were based on relative dating, a method that places sites in order without pinning them to a precise calendar. But something about ‘Ubeidiya felt older, deeper, more ancient than the numbers suggested.

So the scientists returned. They came armed not with shovels alone, but with three powerful tools designed to measure time itself.

Their findings, now published in Quaternary Science Reviews, suggest that ‘Ubeidiya is among the oldest known sites of early humans outside of Africa.

The Stones That Speak of Ancient Hands

The reason ‘Ubeidiya matters so deeply lies in what it preserves. The site contains early evidence of the Acheulean culture, recognizable by its large bifacial stone tools—carefully shaped tools worked on both sides. These were not crude strikes against stone. They were deliberate creations.

Alongside these tools are rich collections of animal remains, known as faunal assemblages, including species of both African and Asian origin, some now extinct. The bones and tools rest together in the sediments, a silent partnership hinting at lives once lived on the shores of an ancient lake.

For researchers, this combination is precious. It provides a window into the world our ancestors encountered as they moved beyond Africa. But to understand the story, one must know when it happened.

And that question had resisted clear answers for decades.

Measuring Time with Cosmic Rays

To solve the puzzle, the team led by Prof. Ari Matmon of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Prof. Omry Barzilai of the University of Haifa, and Prof. Miriam Belmaker of the University of Tulsa turned to a method that sounds almost like science fiction: cosmogenic isotope burial dating.

The principle is elegant. When rocks sit exposed at Earth’s surface, they are constantly struck by cosmic rays. These high-energy particles create rare isotopes within the minerals. But once the rocks are buried, shielded from further bombardment, those isotopes begin to decay at predictable rates.

In other words, burial starts a clock.

By measuring how much of these isotopes remain, scientists can calculate how long the rocks have been hidden underground. It is as if the stones themselves record the moment they disappeared from sunlight.

When the team applied this method at ‘Ubeidiya, they began to glimpse an age far older than previously believed.

The Memory of a Reversed World

But one clock is never enough when rewriting human history. The researchers turned to another archive of time hidden in the sediments themselves: the record of Earth’s magnetic field.

As layers of lake sediment settle, tiny particles within them align with the direction of the planet’s magnetic field at that moment. Once locked in place, they preserve a magnetic signature. Over geological time, Earth’s magnetic field has flipped many times. These reversals are well documented and can be matched to specific periods.

The sediments at ‘Ubeidiya showed that they formed during the Matuyama Chron, a span of time that began more than two million years ago. This magnetic fingerprint placed the site firmly within a much older chapter of Earth’s history than the earlier estimates suggested.

It was another piece of the puzzle clicking into place.

Tiny Shells, Immense Time

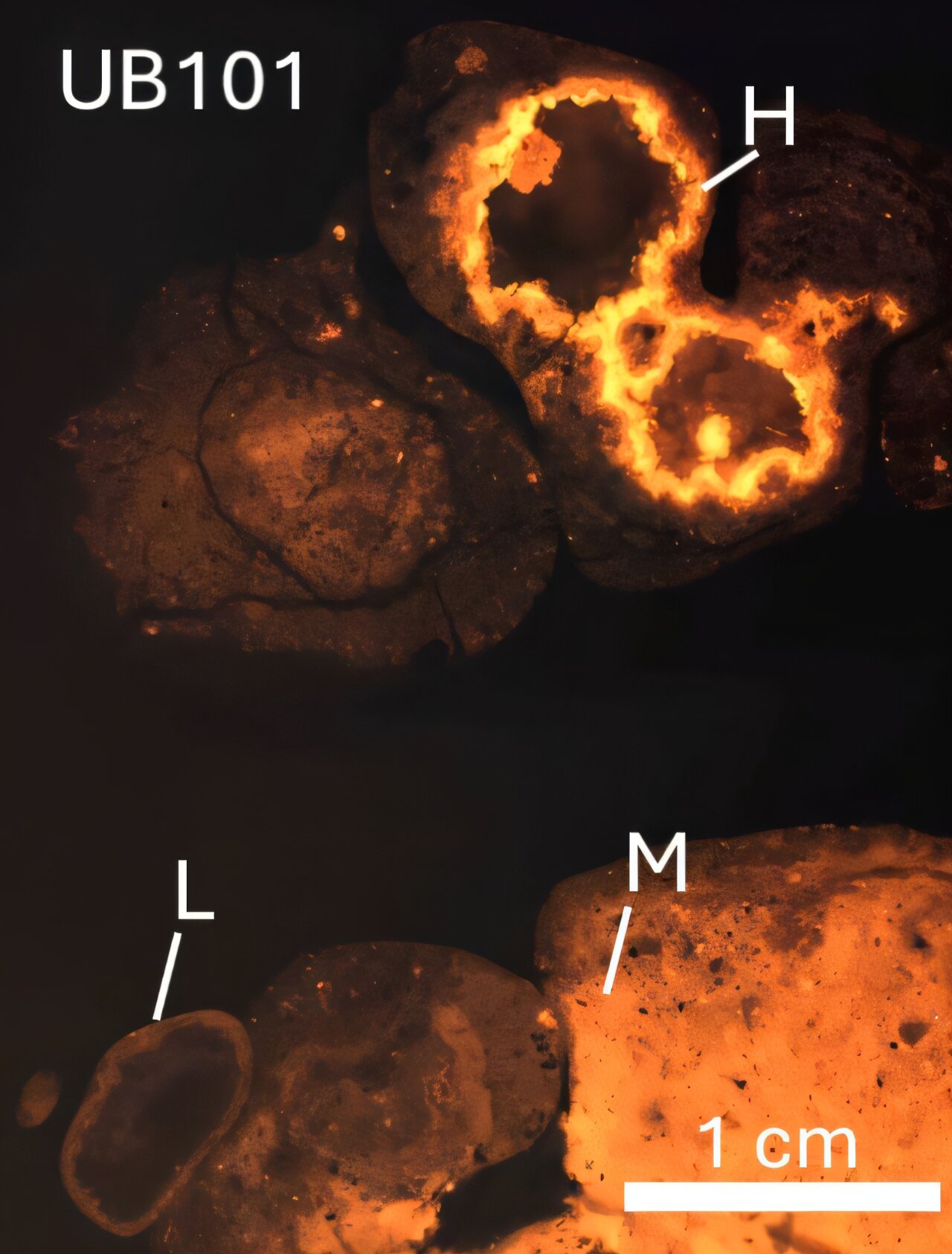

The third method the researchers used focused on something much smaller: fossilized Melanopsis shells embedded in the sediments. These freshwater snails once lived in the lake environment that covered the area.

The team applied uranium-lead dating to the shells. This technique measures the decay of uranium into lead within minerals, providing a minimum age for the layers in which the fossils—and the stone tools—were found.

The shells confirmed what the cosmic isotopes and magnetic signals were already whispering. The layers containing the tools were far older than previously thought.

Three independent methods. Three different ways of reading time. One converging answer.

At least 1.9 million years old.

A Scientific Puzzle Almost Too Old

Yet the path to this conclusion was not smooth.

When the researchers first analyzed the isotopes, the results suggested an astonishing age of 3 million years. That figure clashed sharply with paleomagnetic, paleontological, geological, and archaeological evidence. Something was off.

Instead of discarding the data, the team dug deeper. They realized that the sediments at ‘Ubeidiya have a complex history of movement within the Dead Sea rift. Layers had not simply been deposited and left untouched. They had been recycled—buried, re-exposed, transported, and redeposited along the ancient lake shoreline.

This exposure-burial history explained the unexpectedly old isotope signals. The rocks had lived more than one geological life before settling into their current position.

By modeling this history carefully, the researchers reconciled the conflicting dates. The apparent three-million-year signal was not the age of human activity, but a remnant of the sediments’ earlier journey through the rift valley.

The puzzle resolved itself not by ignoring the anomaly, but by understanding it.

A World Expanding Beyond Africa

With the revised age established, ‘Ubeidiya takes on new significance. At around 1.9 million years old, it is roughly the same age as the well-known Dmanisi site in Georgia.

This suggests something remarkable. Early humans were spreading into different regions at roughly the same time. The movement out of Africa was not a single hesitant step, but part of a broader expansion.

Even more intriguing is what the site reveals about technology. The findings imply that two different stone tool traditions—the simpler Oldowan tradition and the more advanced Acheulean—may have migrated from Africa at the same time, carried by different groups of hominins venturing into new territories.

This challenges the idea of a neat, linear technological progression tied to geography. Instead, it paints a more dynamic picture, with multiple groups moving, experimenting, and adapting across landscapes.

In the sediments of ‘Ubeidiya, the evidence suggests that human evolution was already complex nearly two million years ago.

Why This Changes the Story of Us

The importance of this research reaches beyond one site in the Jordan Valley. By pushing the age of ‘Ubeidiya back to at least 1.9 million years, scientists are refining the timeline of one of the most transformative chapters in our past: the spread of early humans beyond Africa.

Accurate dates are not mere numbers. They anchor our understanding of when technologies emerged, when animals migrated, and when ancient landscapes were inhabited. They shape how we reconstruct the journeys of our ancestors.

This study also demonstrates the power of combining multiple advanced techniques. Cosmogenic isotope burial dating, paleomagnetic analysis tied to the Matuyama Chron, and uranium-lead dating of Melanopsis shells worked together to create a clearer, more reliable timeline. Each method alone offered clues. Together, they told a coherent story.

Perhaps most importantly, the research shows that even long-studied sites can surprise us. Beneath familiar ground, new evidence can rewrite history when examined with fresh tools and careful reasoning.

In the quiet layers of ‘Ubeidiya, stones shaped by ancient hands now sit anchored in deeper time. Nearly two million years ago, early humans stood on the shores of a paleo-lake, crafting tools and sharing a world with animals that no longer roam the Earth.

Thanks to this new timeline, their presence feels closer and clearer. The clock beneath the Jordan Valley has been reset, and with it, our understanding of when—and how—our ancestors began to explore the wider world.

Study Details

A. Matmon et al, Complex exposure-burial history and Pleistocene sediment recycling in the dead sea rift with implications for the age of the Acheulean site of ‘Ubeidiya, Quaternary Science Reviews (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2026.109871