TEL DAN, ISRAEL — Beneath the sun-soaked soil of northern Israel, where the River Jordan is born from crystalline springs, a whisper from the ancient world has resurfaced. In a groundbreaking study published in the journal Levant, Dr. Levana Tsfania-Zias has pieced together a centuries-old ritual that blends the sacred with the personal, the spiritual with the physical: the act of purification through water at the Phoenician sanctuary of Tel Dan.

For nearly five hundred years, worshipers—some from nearby hills, others perhaps from distant lands—may have paused at this temple to wash away more than dust. They came to cleanse themselves in preparation for contact with the divine. Dr. Tsfania-Zias’s findings shed light on a surprisingly intimate practice woven into the heart of religious life—ritual cleansing not as a spectacle, but as a quiet, embodied act of devotion.

A Sacred Hill With Many Stories to Tell

Tel Dan, perched on a Bronze Age rampart and framed by the natural springs that feed the upper Jordan, is no stranger to history. The site has yielded a treasure trove of finds since Avraham Biran began excavations in 1969. Over the decades, successive teams, including David Ilan and Yifat Thareani from the Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology, uncovered layers of occupation stretching across centuries—from Canaanite roots to Israelite rule, and later, Greco-Roman influences.

But it is the temple at the center of the sacred precinct—stoic and rectangular, with three connected rooms—that serves as the focus of this new narrative. Within its worn stones lies a hidden rhythm of religious practice now brought back to life.

The God of Dan and the Silence of Stones

In 1976, archaeologists made a curious discovery: a limestone slab inscribed in both Greek and Aramaic. “To the God who is in Dan, Zoilos made a vow,” it reads. And again: “In Dan(?) a vow of Zilas to God.” These fragmentary lines—spare, yet evocative—offer tantalizing clues. But who was the god of Dan?

The answer is elusive. Some early scholars linked the deity to the God of Israel. Others argued for a more ambiguous, possibly local figure. In Phoenician and broader Near Eastern traditions, gods were often named after cities—“the Lord of Tyre,” “the God of Ekron”—a practice that obscures identity but anchors worship in place.

Even without a name, the rituals of this god come into sharper focus through archaeological evidence: rituals that centered not just on sacrifice or prayer, but on cleansing—on the symbolic and physical act of washing away the mundane to touch the sacred.

The Priest’s Bath: A Room Apart

After the Seleucid conquest, the original temple was destroyed. But the people rebuilt. And in that rebuilding, they preserved the layout and expanded its ritual elements.

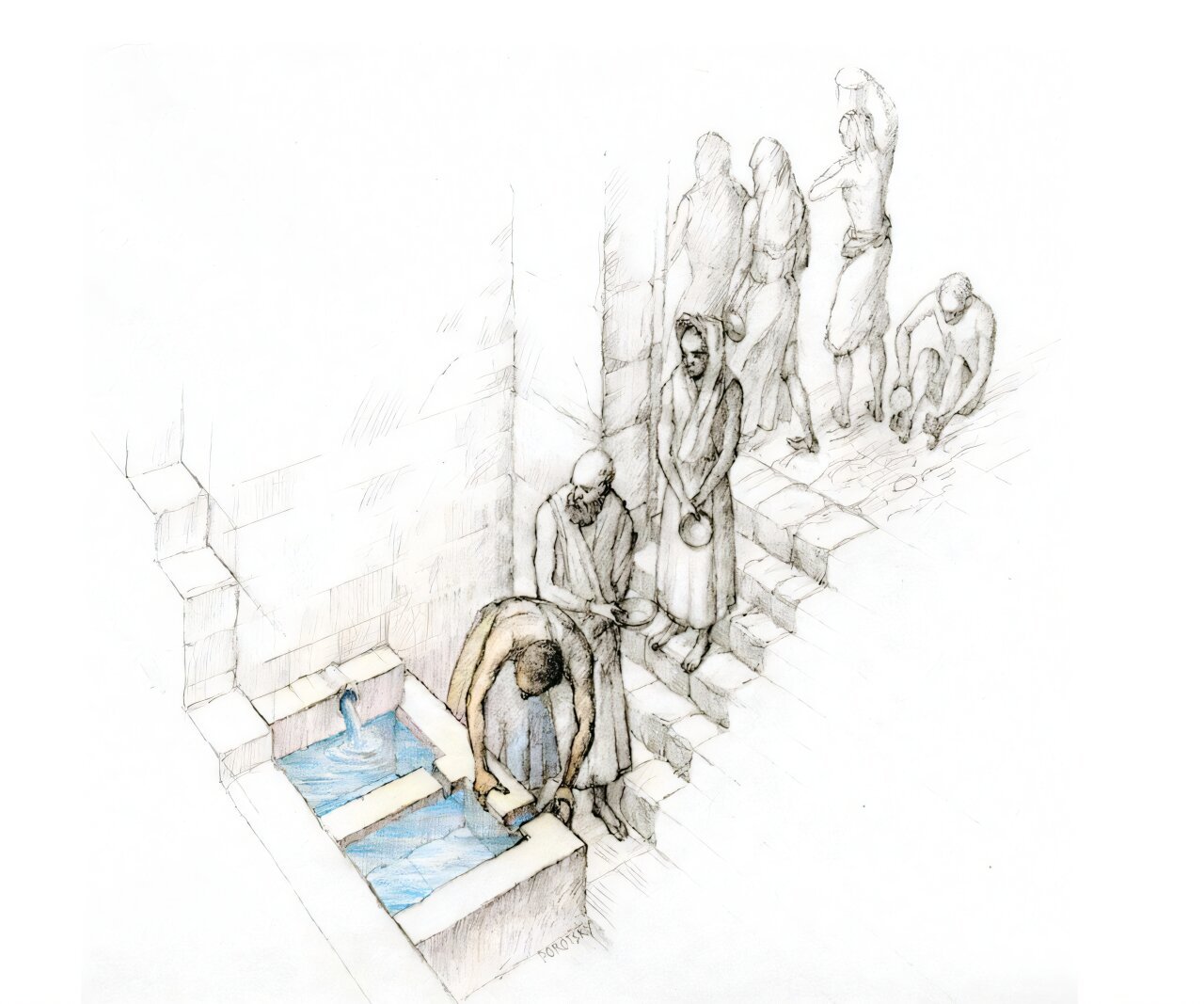

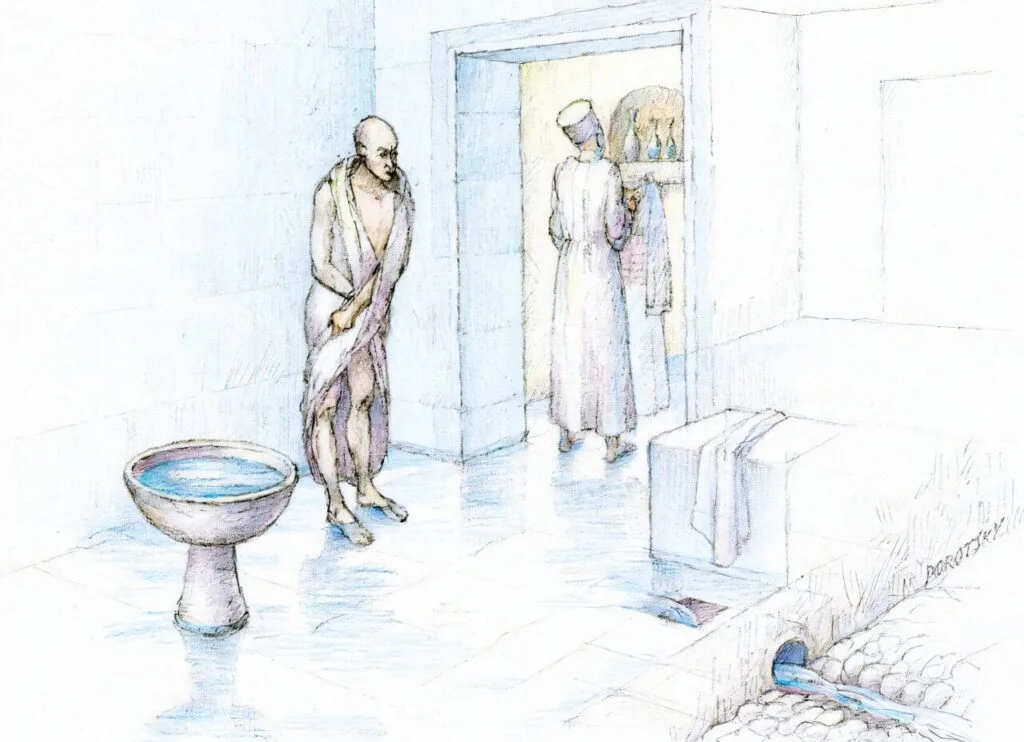

What emerged was a new architectural feature: a modest bathing unit, hidden from the eyes of the public. The bathing complex consisted of two connected rooms—a yellow-plastered dressing space, and beyond it, a blue-plastered room housing the basin. The separation, the color coding, the westward entrance that bypassed the outer porch—they all hint at a ritual meant not for the masses, but for a select few.

This was not a luxurious bathhouse. It was too small for full-body immersion, and there was no hypocaust system to heat the water. This was cleansing in its rawest form: cold, standing, purposeful. Likely performed by priests before entering the inner sanctuary, the adyton, where only the most sanctified dared tread.

It’s a scene easy to imagine: a robed figure stepping into the cold stone chamber, washing his arms, face, feet—each movement deliberate, each drop of water a symbolic barrier between the worldly and the divine.

Pilgrims Return to a Forgotten Sanctuary

Centuries passed. The temple fell silent. For nearly 200 years, nature crept over its stones. But then, sometime in the late 1st to early 4th century CE, Tel Dan stirred again.

In this Middle to Late Roman period revival, the temple changed roles. No longer solely a place for priests, it welcomed pilgrims. A Fountain House was added—an innovation that mirrored wider Greco-Roman practices of public water structures at religious sites. Here, visitors could wash themselves before entering the sacred precinct.

Simple clay vessels, unremarkable at first glance, were found near the washing area. These were not discarded trash, but part of a deeper ritual tradition. Pilgrims likely purchased these vessels, used them in their purification rites, and then broke them—a symbolic gesture mirrored in biblical traditions, where clay vessels used for holy purposes were often shattered to prevent reuse.

The site became not just a sanctuary but a place of spiritual preparation. A threshold, where body and soul were made ready to meet the divine.

A Local Sanctuary with Distant Echoes

Despite the ritual importance of the site, Dr. Tsfania-Zias is careful not to overstate its political or religious dominance in the region. “I believe it primarily served as a local sanctuary for the nearby population,” she explains. But the story does not end there.

The presence of imported ceramics and the bilingual inscription hint at something more. Tel Dan, while local in character, likely attracted travelers from farther afield—people drawn by the temple’s renown, its waters, its god whose name we may never know.

Even in its humbleness, Tel Dan was part of a larger network of sacred spaces that linked people across borders, across languages, across cultures. A shared human longing for purification, connection, meaning.

Mysteries Still Buried in the Earth

Dr. Tsfania-Zias is not done yet. “Looking ahead, we are planning to excavate additional squares in Area T,” she says. It’s a modest sentence, but for archaeologists, it carries weight. More squares means more stories, more chances to piece together the fragmented mosaic of the past.

There is still much we don’t know. How did Tel Dan’s purification rituals compare to those of Tyre, Sidon, or Carthage? What prayers were said before stepping into the water? What songs were sung, what offerings left behind?

“For now,” says Tsfania-Zias, “there is a lacuna in the available data.” But where the written record ends, the soil may yet speak.

A Legacy in Stone and Water

In the end, the story of Tel Dan is not just about archaeology or ancient religion. It is about us.

It is about the timeless human act of washing not just to clean, but to begin again. It is about the instinct to prepare ourselves—physically, emotionally, spiritually—for something greater. Whether before a god whose name we remember or one long forgotten, the impulse remains.

At Tel Dan, the springs still flow. They have not forgotten. And now, thanks to the work of Dr. Levana Tsfania-Zias and the generations of archaeologists before her, neither have we.

Reference: Levana Tsfania-Zias, Ritual purity among the Phoenicians in the sacred precinct at Tel Dan in the Hellenistic and Roman periods, Levant (2025). DOI: 10.1080/00758914.2025.2498295