Rain is one of the most intimate experiences we have with a planet. On Earth, rain smells like soil and memory. It nourishes forests, feeds rivers, and shapes civilizations. But beyond our world, rain becomes something far stranger—something violent, beautiful, and terrifying. In the wider universe, clouds do not always gather water. Instead, they condense molten glass, sulfuric acid, or even diamonds. These alien rains reveal not only how different other planets are, but how flexible and astonishing the laws of physics can be.

What follows is a journey to nine real, scientifically studied planets—some in our solar system, others orbiting distant stars—where rain defies every earthly expectation. These worlds are not imagined. They are measured, modeled, and observed. And each one forces us to rethink what “weather” truly means.

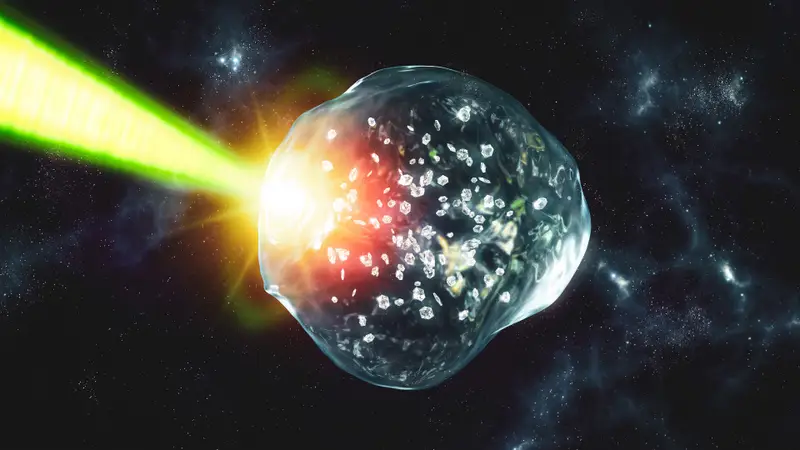

1. Neptune – The Planet of Diamond Rain

Deep within the cold blue depths of Neptune, it may literally rain diamonds.

Neptune is an ice giant, composed largely of hydrogen, helium, and so-called “ices” like water, methane, and ammonia under immense pressure. In Neptune’s atmosphere, methane exists in abundance. When methane molecules are subjected to pressures millions of times greater than Earth’s atmospheric pressure and temperatures exceeding thousands of degrees, something extraordinary happens: the carbon atoms separate and rearrange.

Laboratory experiments using diamond anvil cells and high-powered lasers have demonstrated that under Neptune-like conditions, methane breaks apart and carbon crystallizes into diamond. These diamonds are thought to form deep within the planet’s mantle and then fall like hailstones through layers of superheated fluid.

As they descend, the diamonds may partially melt, forming diamond “rain” that sinks toward Neptune’s core. Some models suggest an ocean of liquid diamond may exist thousands of kilometers below the surface.

This is not gentle precipitation. It is a relentless gravitational descent of crystalline carbon through crushing pressure. Neptune’s diamond rain tells a quiet but powerful story: even the hardest substance we know can behave like water under the right cosmic conditions.

2. Uranus – A Sister World of Diamond Storms

Uranus, often called Neptune’s twin, is another strong candidate for diamond rain—but with its own eerie twist.

Like Neptune, Uranus is rich in methane and experiences enormous internal pressures. The same physical chemistry that produces diamonds on Neptune likely occurs here as well. In fact, some models suggest Uranus may produce even more diamond rain due to differences in temperature gradients and internal structure.

What makes Uranus emotionally haunting is its extreme axial tilt. The planet rotates on its side, resulting in seasons that last over 20 Earth years. During these long seasons, atmospheric dynamics may shift dramatically, influencing how heat moves from the interior outward.

Deep beneath its calm, featureless exterior lies a world of violent transformation. Carbon atoms rain downward, crystallizing into diamonds while the planet silently rolls through space on its side.

Uranus teaches us that even the quietest-looking worlds may hide spectacular internal drama—entire weather systems invisible to the eye, unfolding far below the clouds.

3. 55 Cancri e – The Lava World Where Diamonds May Form

55 Cancri e is an exoplanet that feels less like a place and more like a fever dream.

Located about 41 light-years away, this super-Earth orbits its star so closely that a year lasts only 18 hours. Surface temperatures exceed 2,400 degrees Celsius—hot enough to melt rock. The planet is likely covered in vast oceans of lava, with a thick atmosphere rich in carbon compounds.

Early studies suggested that 55 Cancri e may have an unusually high carbon-to-oxygen ratio, raising the possibility that its interior contains massive amounts of diamond. While later research refined this idea, carbon-rich chemistry remains plausible.

If diamond formation occurs here, it would not be gentle precipitation as on Neptune. Instead, diamond crystals could form within the mantle and be transported upward by volcanic activity, embedded in molten rock seas.

Imagine rain clouds glowing red-hot, storms made of vaporized minerals, and beneath it all, crystalline carbon locked inside a planetary furnace. 55 Cancri e represents a world where Earth’s most precious gemstone is just another geological material—common, brutal, and incandescent.

4. HD 189733 b – The World Where It Rains Molten Glass Sideways

HD 189733 b is one of the most terrifying planets ever studied, and not because of its size—but because of its weather.

This gas giant exoplanet orbits extremely close to its parent star, causing temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius. Its atmosphere contains silicate particles—the same material that makes up sand and glass on Earth.

Under these conditions, silicates vaporize, rise into the atmosphere, and condense into tiny molten glass droplets. But the true horror lies in the wind. Supersonic winds whip around the planet at speeds exceeding 7,000 kilometers per hour.

The result is horizontal rain. Molten glass doesn’t fall gently downward—it is blasted sideways across the planet, forming storms of razor-sharp, superheated glass.

If a human could somehow stand there, they would be shredded instantly, not by heat alone, but by glass rain moving faster than fighter jets. HD 189733 b is a reminder that nature does not need malice to be deadly. Physics alone is enough.

5. Venus – The Planet of Sulfuric Acid Rain

Venus is Earth’s closest planetary neighbor, and perhaps its most tragic.

Once possibly similar to Earth, Venus underwent a runaway greenhouse effect that transformed it into a hellscape. Today, its surface temperature exceeds 460 degrees Celsius, hot enough to melt lead. Above this inferno, thick clouds of sulfuric acid swirl endlessly.

Yes—Venus has rain. But it is rain made of sulfuric acid.

In Venus’s upper atmosphere, sulfur dioxide reacts with water vapor to form sulfuric acid droplets. These droplets fall like rain, but they never reach the surface. As they descend, extreme heat causes them to evaporate before impact, creating a phenomenon known as virga.

Still, the presence of acid rain has profound chemical consequences. It strips metals, corrodes landers, and creates one of the most hostile chemical environments in the solar system.

Venus is a cautionary tale written in clouds. Its acid rain whispers a warning about climate instability, runaway feedback loops, and how fragile habitability truly is.

6. WASP-76b – The Planet Where It Rains Molten Iron

WASP-76b is so extreme that it blurs the line between planet and star.

This ultra-hot gas giant orbits its star so closely that one side permanently faces the star, while the other remains in darkness. On the dayside, temperatures exceed 2,400 degrees Celsius—hot enough to vaporize iron.

Yes, iron becomes a gas.

As iron vapor rises into the atmosphere, powerful winds transport it to the cooler nightside, where temperatures drop just enough for the metal to condense. The result is literal iron rain—molten metal falling through the atmosphere.

This is not metaphor. Spectroscopic observations have directly detected iron vapor and its movement across the planet.

WASP-76b is a world where clouds glow with metal, rain falls as liquid iron, and the sky itself bleeds heat. It is a planet that feels forged rather than formed, shaped by forces closer to stellar physics than planetary calm.

7. Jupiter – The Giant Where It May Rain Helium

Jupiter does not rain diamonds or glass, but its rain may be just as strange.

Deep within Jupiter’s immense atmosphere, hydrogen and helium behave in exotic ways. Under extreme pressure, hydrogen becomes metallic—conducting electricity like a metal. In this environment, helium may separate from hydrogen, forming droplets.

These helium droplets then fall toward the planet’s core in a process known as helium rain.

This rain releases gravitational energy as heat, helping explain why Jupiter emits more energy than it receives from the Sun. It is raining not destruction, but warmth—fueling the planet’s internal engine.

Jupiter’s helium rain is invisible, silent, and constant. It reminds us that not all alien weather is violent. Some is subtle, shaping planetary evolution over billions of years, drip by drip.

8. Saturn – The Golden World of Helium Rain

Saturn shares Jupiter’s helium rain, but in a more dramatic and influential way.

Saturn radiates significantly more heat than expected for its age, and helium rain is the leading explanation. As helium condenses and falls, it releases energy, slowing Saturn’s cooling process.

This rain likely forms deep beneath the planet’s clouds, far from the iconic rings and pastel bands. But without it, Saturn would look very different today.

Emotionally, Saturn’s helium rain feels almost poetic. A planet famous for its beauty is kept warm by invisible precipitation—cosmic rain sustaining a world of rings and storms.

9. Gliese 436 b – The Planet of Burning Ice and Exotic Rain

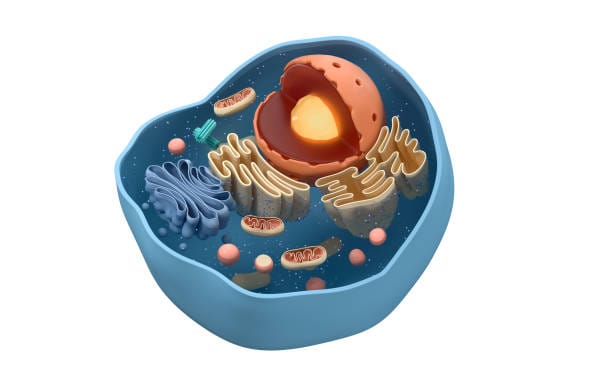

Gliese 436 b is a “hot Neptune” located about 33 light-years away. Despite surface temperatures exceeding 400 degrees Celsius, it is thought to contain vast quantities of water locked in an exotic state known as superionic ice.

In this phase, water molecules break apart under pressure. Oxygen atoms form a rigid lattice, while hydrogen ions move freely, creating a material that is neither solid nor liquid.

If precipitation occurs on Gliese 436 b, it may involve exotic forms of water or volatile compounds raining through an atmosphere shaped by intense radiation and gravity.

This planet challenges our understanding of rain itself. When water no longer behaves like water, rain becomes something unrecognizable—yet still governed by the same universal laws.

A Universe Where Rain Tells the Truth

Rain reveals the soul of a planet. It tells us what the atmosphere is made of, how heat moves, how gravity asserts itself, and how chemistry dances under pressure.

On Earth, rain connects us to memory and survival. On other worlds, rain becomes a storyteller of extremes—diamonds falling through blue darkness, glass slicing sideways through alien skies, acid dissolving hope before it touches the ground.

These planets are real. Their rains are real. And together, they show us that the universe is not limited by familiarity. It explores every possibility physics allows, sculpting worlds where beauty and terror coexist in the same falling drop.

Somewhere out there, clouds gather not with water, but with fire, metal, and crystal. And they rain anyway.