Imagine the Earth not as we know it today, but as it was hundreds of millions of years ago — a world where continents drifted together in the massive supercontinent Pangaea, where strange creatures prowled primeval swamps, and where life itself was still finding its form. Amid this world of chaos and creation, a lineage of predators emerged — powerful, patient, and built for eternity.

These were the ancestors of modern crocodiles — the living fossils, the survivors of apocalypses, the quiet masters of evolution’s most brutal tests. They have outlived the dinosaurs, watched continents split and seas rise, and persisted almost unchanged while countless species vanished into dust.

To understand crocodiles is to peer into the Earth’s ancient soul. They are not just reptiles lurking in tropical rivers; they are living echoes of the deep past — relics from an age before mammals, before birds, before flowers. Their story is not simply one of biology, but of endurance, adaptation, and the raw poetry of life’s struggle to survive.

Before the Crocodiles: The Archosaur Lineage

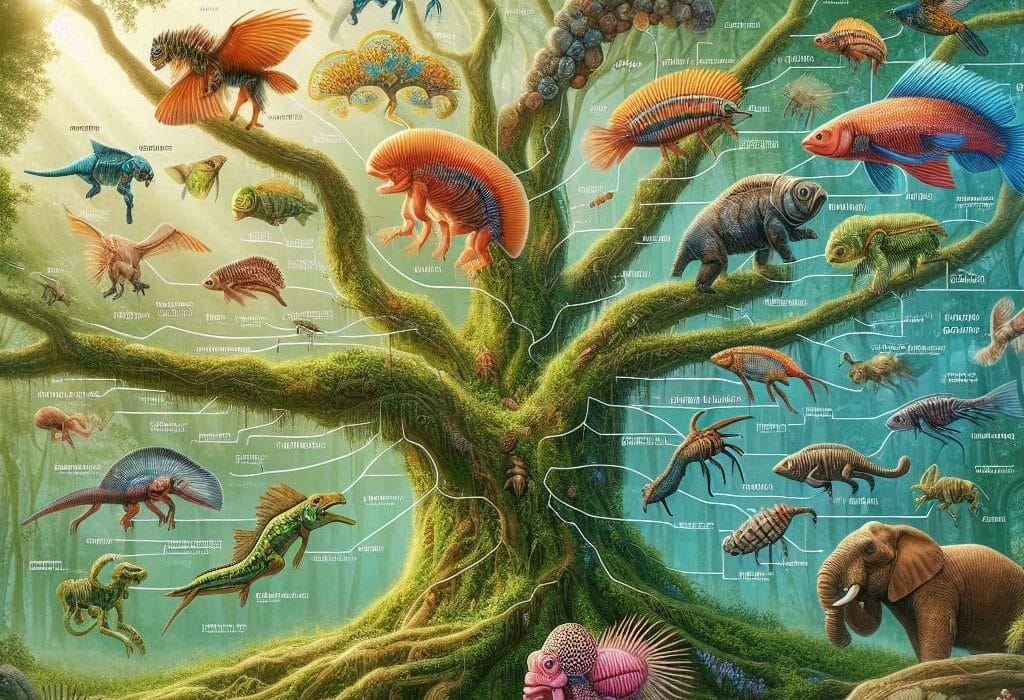

Long before the first true crocodiles appeared, their ancestors had already begun to take shape within a remarkable group known as archosaurs — “ruling reptiles.” The archosaurs were the dominant vertebrates of the Triassic Period, around 250 million years ago, and they gave rise to two great dynasties that would shape the history of life: the crocodile-line archosaurs (pseudosuchians) and the bird-line archosaurs (which would later evolve into dinosaurs and ultimately, birds).

The earliest pseudosuchians were agile, land-dwelling predators with upright legs and fast, active metabolisms. Contrary to the slow, swamp-dwelling image we often associate with crocodiles today, their ancestors were sprinting hunters, built for pursuit. Some even stood on two legs, while others resembled armored wolves with elongated skulls and serrated teeth.

Among these early forms was Postosuchus, a formidable carnivore of the Late Triassic that could reach up to five meters in length. With sharp, recurved teeth and a gait that hinted at bipedalism, it was one of the apex predators of its time. Though Postosuchus and its kin are not true crocodiles, they represent the ancient roots of the crocodilian family tree — a family that was already diverging from the dinosaur lineage during the dawn of the Mesozoic Era.

The World That Forged Them

The Triassic Earth was a land of fire and rebirth. Following the greatest mass extinction in history — the Permian extinction, which wiped out nearly 90% of marine species and 70% of land species — ecosystems were fragile but bursting with innovation.

Volcanic eruptions darkened the skies, while deserts stretched across the heart of Pangaea. Yet, life persisted. The survivors of that catastrophe, including the early archosaurs, adapted rapidly to fill the empty ecological spaces left behind. It was in this crucible of destruction and renewal that the crocodile lineage first took shape.

The climate of the Triassic favored reptiles with tough, scaly skin and efficient lungs. Warm, oxygen-poor air made survival difficult for creatures dependent on rapid respiration, but archosaurs evolved advanced breathing systems that would later allow their descendants — crocodiles, dinosaurs, and birds — to dominate the world.

The Dawn of the Crocodylomorphs

By around 230 million years ago, the first true crocodylomorphs had appeared. These early crocodile relatives were small, slender, and fast-moving. They bore little resemblance to the semi-aquatic ambush predators we know today.

Creatures such as Saltoposuchus and Hesperosuchus were about the size of a housecat, with long legs and lightweight bodies built for agility. They lived primarily on land, hunting small prey and insects. Their skulls were narrow and their limbs upright — adaptations for active, terrestrial life.

Unlike their lumbering descendants, these ancient crocodylomorphs were sprinters. Their bones show evidence of high metabolic activity, suggesting that they were warm-blooded or at least capable of maintaining elevated body temperatures.

This period marked the true divergence of the crocodilian and dinosaurian lineages — two evolutionary experiments that would define the Mesozoic world in very different ways. While the dinosaurs conquered the land and sky, the crocodile lineage began its long, winding journey toward the water.

When Crocodiles Ruled the Land

As the Triassic gave way to the Jurassic, about 200 million years ago, the world changed dramatically. The supercontinent Pangaea began to break apart, forming new coastlines, lakes, and river systems. These environments became the perfect arenas for crocodile evolution.

Early Jurassic crocodylomorphs diversified into an astonishing variety of forms. Some remained on land, while others ventured into aquatic habitats. Among them was the sphenosuchians, small and fox-like with long, narrow jaws — nimble hunters of the early Mesozoic ecosystems.

But as the Jurassic progressed, larger and more aquatic species began to dominate. The shift from land to water wasn’t abrupt — it was a gradual adaptation driven by opportunity. As dinosaurs rose to power on land, crocodile ancestors found refuge and new niches along the water’s edge.

The Rise of the Marine Crocodiles

One of the most dramatic transformations in crocodilian history came with the emergence of the thalattosuchians, or “sea crocodiles,” during the Jurassic Period. These were fully marine reptiles, perfectly adapted to life in the ocean.

Species such as Metriorhynchus and Dakosaurus roamed the Jurassic seas like reptilian dolphins. They had streamlined bodies, paddle-like limbs, and tail flukes for propulsion. Their nostrils were positioned high on the snout, allowing them to breathe at the surface like modern whales.

Dakosaurus, in particular, was a fearsome predator — a marine crocodile with a short, massive skull and serrated teeth built for cutting through flesh. It occupied the same ecological role as sharks or orcas, hunting fish, cephalopods, and other marine reptiles.

These oceanic crocodiles represent one of the most fascinating evolutionary experiments in reptilian history — the transformation of a terrestrial predator into a sleek, hydrodynamic hunter of the deep.

But as the Cretaceous dawned, the seas changed again, and with them, the fortunes of these marine species began to fade.

The Age of Giants: Cretaceous Crocodiles

The Cretaceous Period, beginning about 145 million years ago, ushered in a golden age for crocodilians. It was a time of diversification, when these reptiles occupied almost every available niche — from rivers and lakes to open seas and even dry plains.

Among the most extraordinary of these ancient crocodiles was Sarcosuchus imperator, often called the “SuperCroc.” Measuring up to 12 meters (40 feet) in length, it was one of the largest crocodilians ever to have lived. Sarcosuchus stalked the rivers of Cretaceous Africa, its immense jaws lined with conical teeth capable of crushing bone and turtle shells.

Another remarkable species, Deinosuchus, haunted the swamps of North America. Roughly the size of a city bus, it could ambush dinosaurs that ventured too close to the water’s edge. Bite marks found on fossilized dinosaur bones reveal the terrifying truth — Deinosuchus was a predator powerful enough to drag a hadrosaur beneath the surface and drown it.

Not all Cretaceous crocodiles were giants. Some were surprisingly small and specialized. Armadillosuchus, for instance, evolved armor plates and lived more like a land-dwelling mammal, burrowing and feeding on insects. Others, like Anatosuchus, developed broad, duck-like snouts for scooping prey from muddy waters.

This era demonstrated the incredible adaptability of the crocodilian form. Whether in water or on land, as hunters or scavengers, they thrived in nearly every environment the planet had to offer.

Surviving the End of the Dinosaurs

Then came catastrophe. About 66 million years ago, a massive asteroid struck the Earth near what is now the Yucatán Peninsula, unleashing one of the most devastating mass extinctions in history. The skies darkened with ash, temperatures plummeted, and the ecosystems of the Mesozoic collapsed.

The great dinosaurs perished. The marine reptiles vanished. Forests burned, oceans acidified, and countless species were erased from existence.

Yet, through all this chaos, the ancestors of modern crocodiles endured.

Their survival was not mere luck. Crocodiles were superbly adapted for resilience. They could go months without food, withstand harsh conditions, and live both in water and on land. Their slow metabolisms allowed them to survive long periods of scarcity, and their opportunistic diets — feeding on fish, carrion, or anything edible — gave them an edge when food was scarce.

In the dark aftermath of the Cretaceous extinction, when so much life had been extinguished, crocodiles waited in the rivers and swamps, biding their time. And when the Earth healed, they emerged once again, almost unchanged.

The Age of the Modern Crocodiles

By the Paleogene Period, about 60 million years ago, the ancestors of today’s crocodiles had already begun to take on familiar forms. The modern group, Crocodylia, includes three main families:

- Crocodylidae (true crocodiles),

- Alligatoridae (alligators and caimans), and

- Gavialidae (gharials).

These families share a common ancestor that likely lived shortly after the dinosaurs’ extinction. Over the next millions of years, they radiated into diverse habitats across the world — rivers, estuaries, mangrove swamps, and even brackish coastal waters.

Alligators adapted to cooler climates, such as those found in North America and China. Crocodiles became more salt-tolerant, spreading into tropical regions across Africa, Asia, and Australia. The gharials specialized in fish-eating, developing long, slender snouts ideal for slicing through water.

The physical design of crocodiles — powerful jaws, armored skin, stealthy movement — was so efficient that evolution needed to change little. They became, in effect, living fossils: survivors from a world that time itself seemed to forget.

The Anatomy of Survival

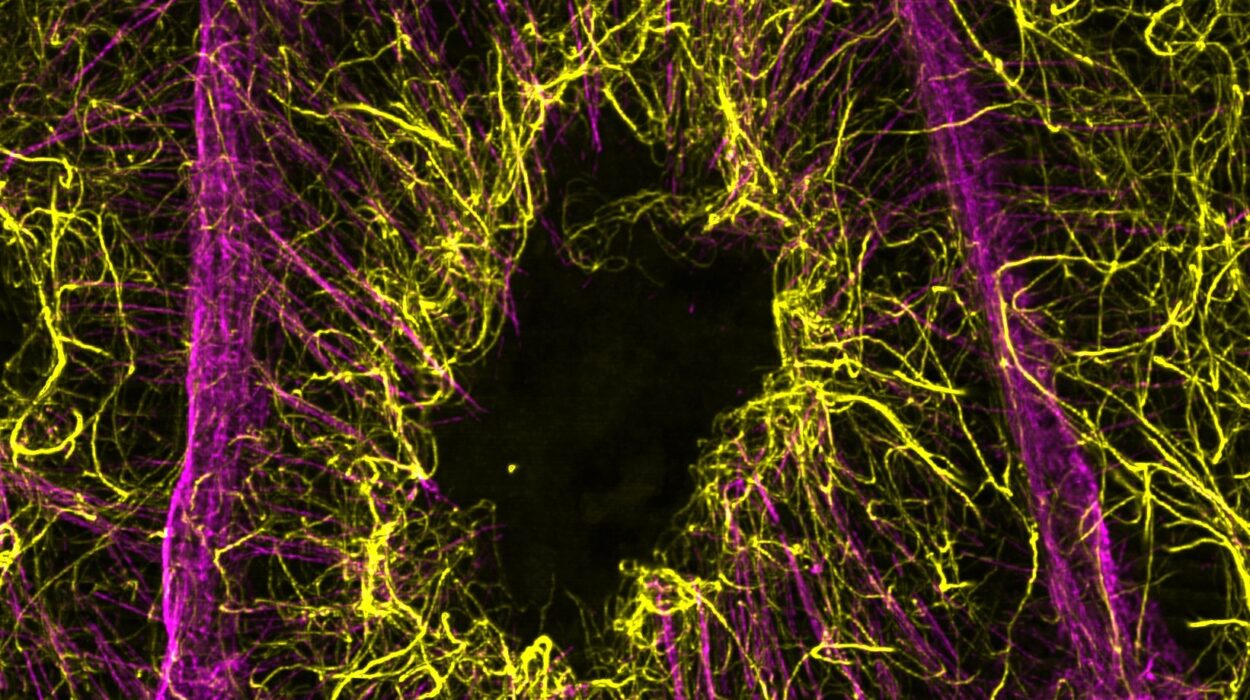

The crocodile’s success lies in its perfection as a predator. Every feature of its anatomy speaks of survival refined over eons.

Its armor — thick, bony plates called osteoderms — protects it like a living shield. Its eyes and nostrils sit atop the skull, allowing it to breathe and see while almost entirely submerged. Its tail is a muscular engine, propelling it silently through the water with deadly precision.

Crocodiles possess one of the most powerful bites in the animal kingdom, capable of crushing bones with thousands of pounds of force. Yet they can also move with astonishing delicacy, gently carrying their young or eggs in their mouths.

They are ancient machines of instinct — both brutal and tender, primitive yet sophisticated.

Their physiology is equally remarkable. Crocodiles can slow their heart rates to a few beats per minute, allowing them to remain underwater for over an hour. They can also survive long periods of starvation, conserving energy through astonishing metabolic control.

Even their reproductive strategies are fine-tuned by time. Female crocodiles carefully build and guard nests, showing a degree of parental care rare among reptiles. When the hatchlings emerge, the mother carries them gently to the water — a gesture of fierce protection that echoes across 200 million years of evolution.

The Living Fossil and Its Future

Today’s crocodiles are among the closest living links to the ancient world. They have changed so little since the time of the dinosaurs that studying them is like looking through a window into the Mesozoic.

And yet, even these masters of endurance face new challenges. Habitat loss, pollution, and hunting have driven several species to the brink of extinction. The slender-snouted crocodile, the Philippine crocodile, and the gharial now teeter on the edge, victims not of asteroids or volcanic winters, but of human ambition.

The irony is profound: creatures that survived cosmic cataclysms now struggle against the encroachments of their youngest evolutionary relatives — us.

But hope remains. Conservation programs across the globe are working to protect and restore crocodilian populations. Sanctuaries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas are proving that with care and respect, these ancient beings can continue their long story.

When we preserve crocodiles, we preserve more than a species — we preserve a living chapter of Earth’s evolutionary epic.

The Philosophy of a Predator

There is something almost philosophical about the crocodile’s presence. It embodies patience — the stillness before action, the calm before chaos. In its motionless vigil, floating beneath the surface, there is the wisdom of ages: the understanding that survival is not about speed or intellect alone, but endurance, timing, and adaptability.

For over 200 million years, crocodiles have been both predators and witnesses. They have seen the rise and fall of dinosaurs, the birth of mammals, and the coming of humanity. They remind us that survival is not just a matter of dominance, but of balance — of knowing when to strike and when to wait.

The Crocodile as a Mirror of Time

To look into the eyes of a crocodile is to see time itself reflected back — cold, ancient, and unbroken. Its gaze carries the memory of primordial swamps, of thundering herds of dinosaurs, of fiery skies and silent extinctions.

When you watch a crocodile slip into the water, vanishing without a ripple, you are witnessing the same motion that its ancestors performed millions of years ago. There is no rush, no panic — only purpose.

In an age of fleeting things, the crocodile endures. It is a testament to the resilience of life, to nature’s genius for survival, and to the beauty of continuity amid change.

The Endless River of Evolution

The story of the crocodile is not merely about a predator; it is about persistence. From land-dwelling archosaurs to river-dwelling giants, from extinction events to the modern wetlands, the crocodile lineage flows like a great, ancient river — winding, enduring, unstoppable.

Every ripple of that river carries the memory of evolution’s grand experiments: the armored backs of Triassic hunters, the sleek bodies of Jurassic sea-crocs, the monstrous jaws of Cretaceous titans, and the quiet patience of the modern swamp-dwellers.

They are all connected — chapters of the same timeless saga written in bone, blood, and water.

Conclusion: The Immortals of the Earth

The ancient origins of crocodiles tell one of the greatest survival stories ever written. From the ashes of the Permian extinction to the dawn of humanity, they have persisted with a quiet, unwavering strength.

They are not relics of the past but living symbols of nature’s endurance. Their bodies bear the signature of a world long gone, yet they continue to thrive in ours — a bridge between the Mesozoic and the modern, between what was and what still is.

When we see a crocodile basking on a riverbank, we are not merely looking at an animal — we are gazing into the deep history of the Earth itself. In their silence lies a truth older than mountains: that life, in its purest form, does not need to change to survive.

The crocodile is time made flesh — a living monument to the ancient world, and a reminder that sometimes, to endure, is the greatest triumph of all.