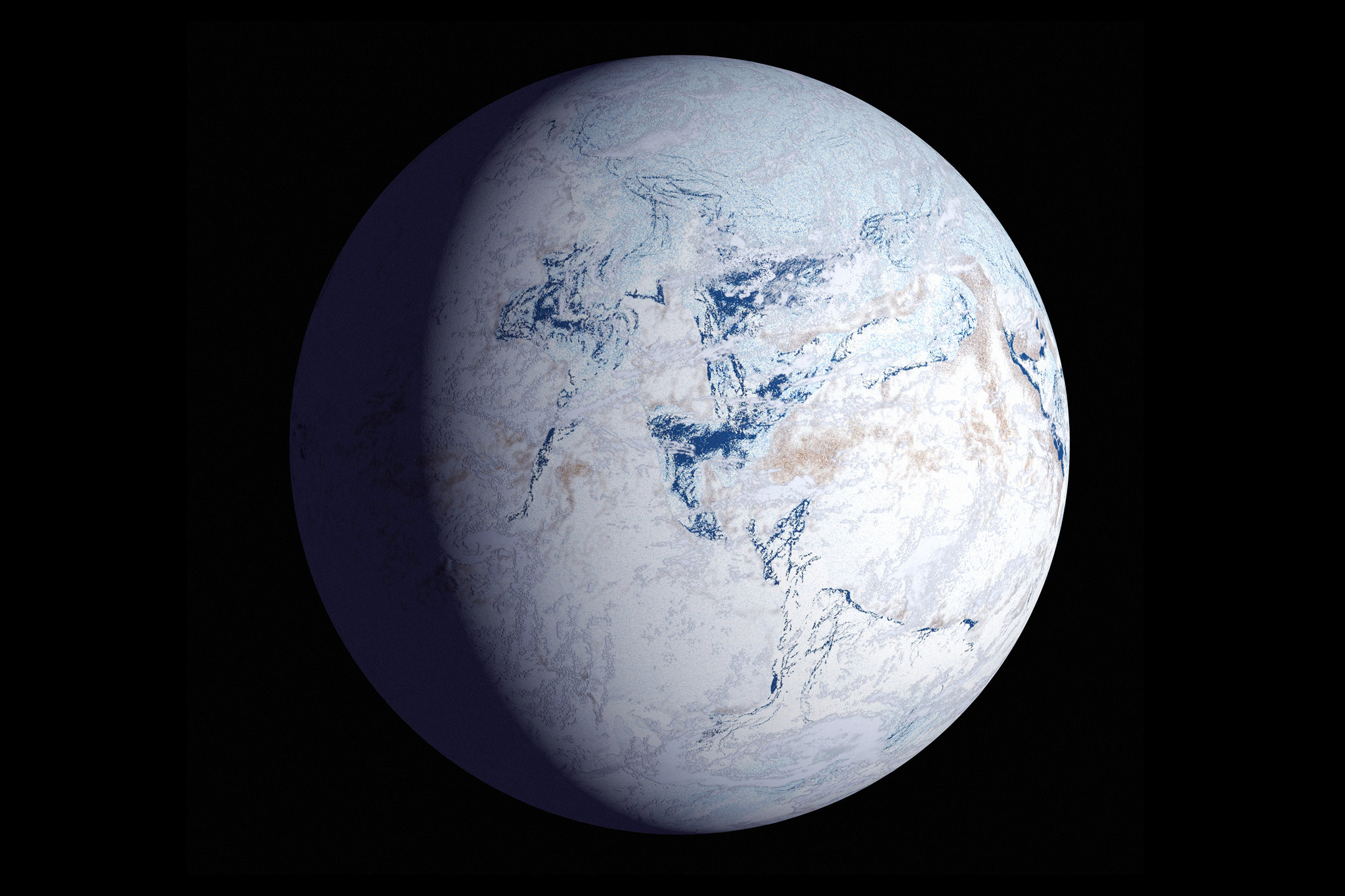

The Earth we know today feels alive and generous. Blue oceans breathe moisture into the sky. Forests exhale oxygen. Life thrives from the equator to the poles. But this familiar world has not always been so kind. Long before humans existed, long before animals or even complex plants, Earth repeatedly plunged into deep freezes so extreme that the planet may have looked like a frozen marble drifting through space. Scientists call these episodes Snowball Earth events, periods when ice advanced from the poles to the tropics, possibly encasing the entire planet in ice.

These were not gentle ice ages like the ones that shaped mammoths and glaciers. These were global catastrophes, times when survival itself was pushed to the brink. Yet paradoxically, these frozen chapters may have played a critical role in shaping the modern world, even paving the way for complex life.

Here are seven moments in Earth’s deep past when our planet may have transformed into a near-lifeless snowball—and why it didn’t stay frozen forever.

1. The Pongola Glaciation (Around 2.9 Billion Years Ago)

The earliest suspected Snowball-like event occurred so far back in time that Earth was almost unrecognizable. Around 2.9 billion years ago, the planet was dominated by volcanic landscapes, shallow oceans, and simple microbial life. The Sun was significantly dimmer than it is today, delivering less energy to Earth’s surface.

Geological evidence from ancient rock formations in what is now southern Africa suggests widespread glaciation near the equator. This is astonishing, because ice at such low latitudes implies a planet locked in extreme cold. At the time, Earth’s atmosphere lacked significant oxygen and greenhouse gas levels may have fluctuated wildly due to volcanic activity and chemical reactions in the oceans.

This early freeze likely resulted from a delicate imbalance. Reduced solar energy, combined with limited atmospheric warming, may have allowed ice to spread rapidly. Once ice reached lower latitudes, it reflected more sunlight back into space, reinforcing the cooling in a runaway feedback loop.

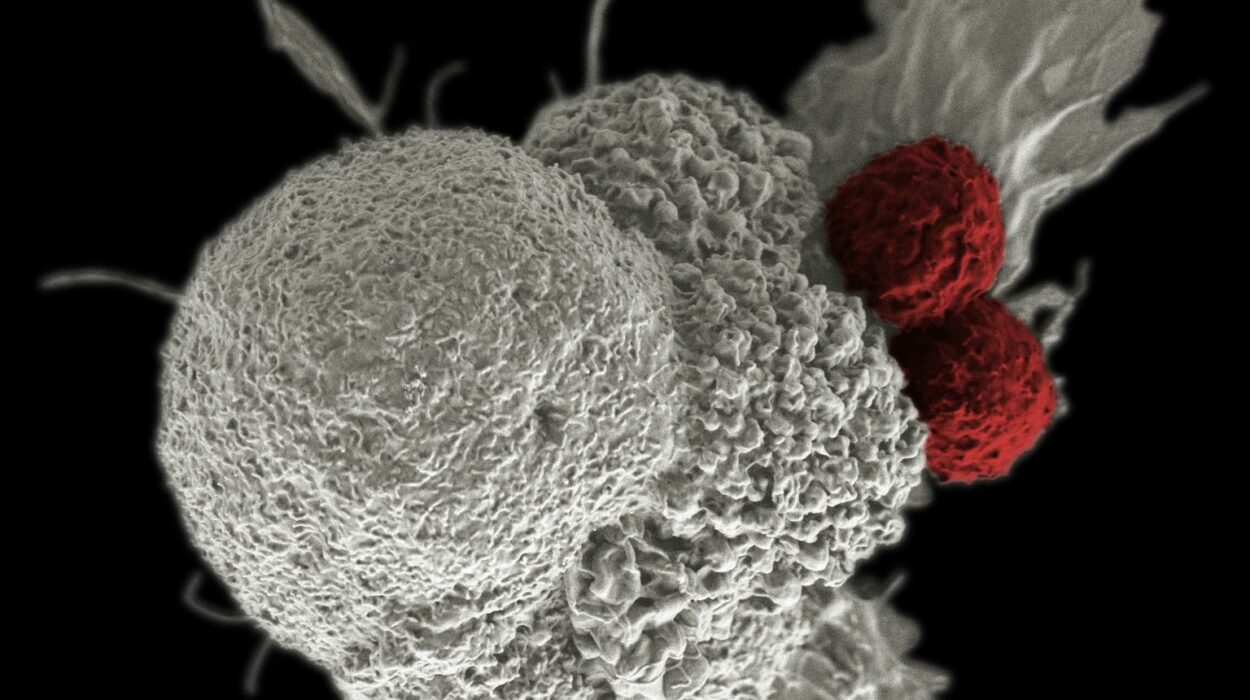

Life at this time was simple, but remarkably resilient. Microbes likely survived near hydrothermal vents, beneath ice-covered oceans, or in isolated warm pockets. The Pongola glaciation hints that even Earth’s earliest biosphere learned how to endure planetary-scale disaster.

2. The Huronian Snowball Earth (2.4 to 2.1 Billion Years Ago)

The Huronian glaciation is the most widely accepted early Snowball Earth event and one of the most dramatic climate shifts in Earth’s history. It coincided with a revolutionary biological transformation known as the Great Oxidation Event, when photosynthetic microbes began producing large amounts of oxygen.

At first glance, oxygen sounds like progress—and it was—but it came with a devastating side effect. Oxygen reacted with methane, a powerful greenhouse gas that had previously helped keep the planet warm. As methane levels collapsed, Earth’s atmospheric blanket thinned, and temperatures plummeted.

Glacial deposits from this era appear across multiple continents, suggesting global-scale ice coverage that lasted hundreds of millions of years. Oceans may have been sealed beneath thick ice sheets, while continents lay buried under glaciers.

This was likely the coldest Earth had ever been. Yet life survived. Some microbes adapted to oxygen-rich conditions, while others retreated into sheltered environments. The Huronian Snowball Earth may have acted as an evolutionary filter, reshaping life and preparing it for more complex futures.

3. The Kaigas Glaciation (Around 750 Million Years Ago)

Fast forward more than a billion years, and Earth was again teetering on the edge of total freeze. The Kaigas glaciation is less certain than other Snowball events, but evidence suggests it marked the beginning of a brutal climatic era.

By this time, continents were clustered differently, possibly forming supercontinents near the equator. This configuration increased weathering of rocks, which pulled carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and locked it away in minerals. Less carbon dioxide meant less heat trapped near Earth’s surface.

Ice began advancing from the poles toward the equator once more. The planet entered a feedback loop where expanding ice reflected sunlight, driving further cooling. The Kaigas glaciation may not have fully frozen Earth, but it pushed the climate system dangerously close to that threshold.

Life was becoming more complex during this time, with early eukaryotic cells emerging. These fragile forms would soon face even harsher tests.

4. The Sturtian Snowball Earth (Around 720 to 660 Million Years Ago)

The Sturtian glaciation is considered one of the most severe Snowball Earth events ever recorded. Geological evidence shows glacial deposits at tropical latitudes on nearly every continent. Ice likely reached the equator, and some models suggest the oceans were sealed beneath ice hundreds of meters thick.

What triggered this freeze was a combination of continental positioning, reduced greenhouse gases, and possibly changes in ocean circulation. Once the ice advanced far enough, Earth’s climate system locked into a frozen state that lasted nearly 60 million years—an unimaginably long time for a planet to remain frozen.

The world during the Sturtian Snowball Earth would have been silent and stark. Ice-covered oceans reflected sunlight like mirrors. Weather systems collapsed. Photosynthesis was severely limited, especially in the oceans.

Yet life endured. Microbes likely survived in cracks within the ice, near volcanic vents, or in thin equatorial regions where ice may have been thinner. This survival against overwhelming odds stands as one of the most astonishing achievements of life on Earth.

5. The Marinoan Snowball Earth (Around 650 to 635 Million Years Ago)

If the Sturtian glaciation was brutal, the Marinoan glaciation was transformative. Often considered the classic Snowball Earth event, the Marinoan freeze left unmistakable geological fingerprints worldwide.

Ice sheets reached the tropics once again, and global temperatures may have dropped below −40 degrees Celsius in some regions. The oceans, trapped beneath ice, became stagnant and chemically altered.

What makes the Marinoan Snowball Earth especially significant is what happened when it ended. Volcanic activity continued throughout the freeze, pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. With weathering shut down under ice, this greenhouse gas accumulated for millions of years.

Eventually, the atmospheric buildup triggered a dramatic reversal. Earth thawed rapidly, possibly in just a few thousand years. Temperatures soared, ice melted, and oceans flooded continents with mineral-rich waters.

Soon after, life exploded in diversity. Within a relatively short geological time, multicellular organisms became more complex, leading toward the Cambrian Explosion. The Marinoan Snowball Earth may have been a crucible, forging the conditions that allowed animals to emerge.

6. The Gaskiers Glaciation (Around 580 Million Years Ago)

The Gaskiers glaciation was shorter and possibly less extreme than full Snowball Earth events, but it still represents a near-global freeze. Evidence from Newfoundland and other regions suggests widespread glaciation during a critical evolutionary window.

This event occurred just before the rise of large, soft-bodied organisms known as the Ediacaran biota. While Earth may not have been completely frozen, ice likely reached unusually low latitudes, disrupting ecosystems and climate stability.

The Gaskiers glaciation may have acted as a selective pressure, eliminating fragile life forms while allowing more adaptable organisms to survive. This pruning effect could have helped shape the evolutionary pathways that led to complex animals.

Rather than being purely destructive, this cold snap may have helped reset biological systems, encouraging innovation in body plans, reproduction, and metabolism.

7. The Late Paleozoic Icehouse (Around 360 to 260 Million Years Ago)

While not a true Snowball Earth, the Late Paleozoic Icehouse deserves mention as a reminder that Earth can remain cold for extraordinarily long periods. During this time, massive ice sheets covered southern continents, including parts of what is now South America, Africa, Antarctica, and Australia.

This prolonged cold period was driven by the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea and the rise of vast forests that pulled carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. While tropical regions remained ice-free, global temperatures were significantly lower than today.

This icehouse world shaped ecosystems profoundly, influencing the evolution of reptiles, insects, and early amphibians. It demonstrated that even without a full Snowball Earth, prolonged cold can restructure life and climate on a planetary scale.

Why the Earth Didn’t Stay Frozen Forever

One of the most haunting questions about Snowball Earth is why the planet ever thawed at all. Once ice reflects enough sunlight, warming becomes nearly impossible. Yet Earth escaped its frozen prisons repeatedly.

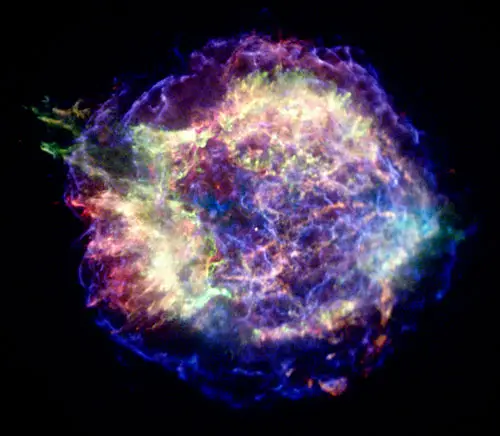

The answer lies beneath the ice. Volcanoes never stopped erupting. They continued releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, even while glaciers dominated the surface. Over millions of years, greenhouse gases accumulated, slowly rebuilding Earth’s heat-trapping shield.

When melting finally began, it happened fast. Ice melted, oceans absorbed heat, and carbon dioxide levels drove intense warming. These rapid transitions reshaped landscapes, oceans, and life itself.

Snowball Earth events remind us that Earth’s climate system has tipping points—and once crossed, recovery can be violent and unpredictable.

What Snowball Earth Teaches Us Today

These ancient freezes are more than curiosities of deep time. They teach us that Earth’s climate is sensitive, interconnected, and capable of dramatic change. Small shifts in atmospheric chemistry, solar energy, or continental arrangement can push the planet into radically different states.

They also tell a story of resilience. Life did not merely survive Snowball Earth—it emerged transformed. Complexity, diversity, and innovation followed catastrophe.

In a strange way, Snowball Earth events reveal something hopeful. Even in the face of global disaster, life adapts. The planet recovers. And from the coldest moments in Earth’s history came the foundations of the vibrant world we inhabit today.

The Earth has been a frozen sphere drifting through space more than once. And each time, it found a way back to life.