For as long as humans have understood the fragility of the heart, they have dreamed of repairing it. Across cultures and centuries, the heart has been imagined as more than a biological pump. It is the seat of emotion, courage, love, and vitality. When the heart fails, life itself seems to falter. Modern medicine has learned how to mend damaged hearts, slow their decline, and in some cases replace them with donor organs. Yet the demand for healthy hearts vastly exceeds the supply. Against this backdrop, a radical idea has emerged from the intersection of biology, engineering, and physics: could we one day print a functioning human heart?

Three-dimensional bioprinting is not science fiction, nor is it a simple extension of conventional 3D printing. It represents a profound shift in how scientists think about building living structures. Instead of printing plastic or metal, bioprinters work with living cells, biological materials, and carefully controlled physical environments. The question of whether a functioning human heart can be printed is therefore not only a technical challenge but a deeply philosophical one. It forces us to ask what it truly means to create life-like systems and whether nature’s most complex organ can be assembled layer by layer.

What Is 3D Bioprinting?

At its core, 3D bioprinting is an additive manufacturing process that uses living cells and biocompatible materials to fabricate structures that resemble biological tissues. Like traditional 3D printing, it relies on digital designs, precise control, and layer-by-layer construction. What makes bioprinting fundamentally different is that the printed product is not inert. It is meant to survive, grow, communicate internally, and perform biological functions.

Bioprinting typically uses bioinks, which are mixtures of living cells and supportive materials such as hydrogels. These hydrogels provide a temporary scaffold that helps cells maintain their shape and spatial organization. Over time, the cells interact, produce their own extracellular matrix, and gradually take over the structural role as the scaffold degrades or integrates.

The process draws heavily on principles from physics, particularly fluid dynamics, materials science, and mechanical engineering. The viscosity of bioinks, the shear forces experienced by cells during printing, and the mechanical stability of printed structures must all be carefully balanced. Too much force can damage cells, while too little structure can cause the printed tissue to collapse. Bioprinting therefore operates at a delicate boundary between the living and the engineered.

Why the Human Heart Is Such a Formidable Challenge

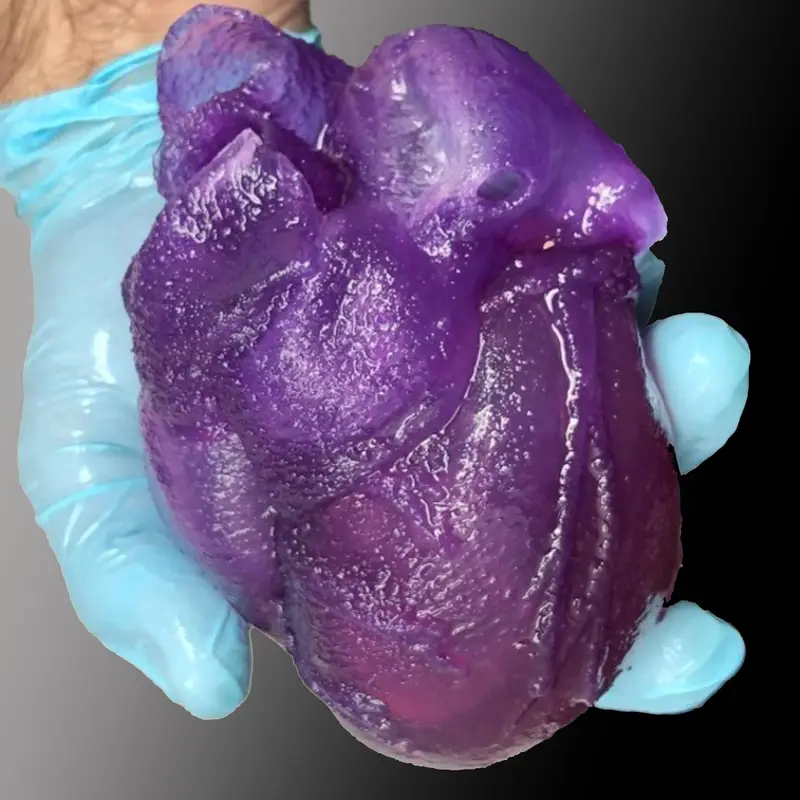

The heart is not just another organ. It is one of the most structurally and functionally complex systems in the human body. A fully developed human heart contains billions of cells, organized into highly specialized tissues that must work in perfect synchrony. Cardiac muscle cells contract rhythmically, electrical signals propagate in precise patterns, valves open and close seamlessly, and blood vessels branch intricately to supply oxygen and nutrients.

Unlike relatively simple tissues such as skin or cartilage, the heart is a dynamic organ. It beats approximately one hundred thousand times a day, responding instantly to changes in physical activity, emotional state, and metabolic demand. Any printed heart must not only resemble the real organ anatomically but also reproduce this extraordinary functional coordination.

From a scientific perspective, this complexity poses multiple challenges. Cells must be positioned with micrometer-scale precision. Vascular networks must be dense and interconnected enough to sustain thick tissue. Electrical conduction pathways must form naturally or be guided artificially. Mechanical properties must be tuned so the tissue can contract forcefully without tearing or stiffening. Each of these challenges alone is significant. Together, they represent one of the most ambitious goals in modern biomedical science.

The Biology of the Heart: More Than Muscle

A common misconception is that the heart is primarily a mass of muscle cells. In reality, cardiac muscle cells, or cardiomyocytes, are only part of the story. The heart also contains fibroblasts that provide structural support, endothelial cells that line blood vessels, smooth muscle cells that regulate vascular tone, and specialized pacemaker cells that initiate each heartbeat.

These cells communicate constantly through chemical signals, electrical impulses, and mechanical forces. This communication is not incidental; it is essential. Cardiomyocytes align in specific orientations to generate efficient contractions. Fibroblasts influence electrical signaling and mechanical stiffness. Endothelial cells regulate blood flow and release molecules that affect muscle function.

For bioprinting, this means that printing a heart is not a matter of depositing one cell type. It requires recreating a living ecosystem in which multiple cell populations coexist and interact. Each cell type must be printed in the right place, in the right proportion, and under conditions that allow it to mature and function appropriately. The heart’s biology resists simplification, and any attempt to recreate it must respect this complexity.

Bioinks: The Living Material of Bioprinting

Bioinks are the lifeblood of bioprinting technology. They must satisfy a demanding set of criteria. From a biological standpoint, they must support cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. From a physical standpoint, they must flow smoothly through printer nozzles, solidify quickly enough to maintain shape, and possess mechanical properties compatible with the target tissue.

Hydrogels are the most commonly used bioink base materials. These water-rich polymers mimic aspects of the natural extracellular matrix that surrounds cells in the body. Materials such as alginate, gelatin-based compounds, collagen, and fibrin have all been explored. Each has advantages and limitations. Some are easy to print but biologically inert, while others are biologically active but mechanically weak.

In the context of heart bioprinting, bioinks must also withstand repetitive mechanical stress. Cardiac tissue experiences continuous cycles of contraction and relaxation. If the printed material is too soft, it may deform irreversibly. If it is too stiff, it may impair cell function and electrical signaling. Achieving the right balance requires deep understanding of both cellular biology and material physics.

Printing Cells Without Killing Them

One of the earliest technical hurdles in bioprinting was cell survival during the printing process. Cells are delicate entities. They can be damaged by excessive pressure, temperature changes, or mechanical shear. Traditional 3D printing methods that work well for plastics or metals are entirely unsuitable for living material.

To address this, bioprinting technologies have evolved to be gentler. Extrusion-based bioprinters push bioink through nozzles using controlled pressure, while inkjet-style printers deposit tiny droplets with minimal force. Laser-assisted bioprinting uses focused energy to propel small volumes of bioink onto a substrate without direct nozzle contact.

Each method involves trade-offs. Higher resolution often comes at the cost of cell viability, while gentler methods may sacrifice structural precision. For heart tissue, where fine spatial organization is critical, these trade-offs are especially important. Researchers must ensure that printed cardiomyocytes not only survive but retain their ability to contract and synchronize after printing.

Vascularization: The Lifeline of Printed Organs

Perhaps the single greatest obstacle to printing a functioning human heart is vascularization. In living organisms, cells are never far from blood vessels. Oxygen and nutrients can only diffuse a limited distance through tissue. Beyond that, cells begin to die. This diffusion limit means that thick, dense tissues require an internal network of blood vessels to survive.

Printing a heart-sized structure without a functional vascular system would result in widespread cell death. Creating such a system is extraordinarily challenging. Blood vessels vary in size from large arteries to microscopic capillaries, forming a hierarchical and interconnected network. They must also be lined with living endothelial cells and capable of responding dynamically to blood flow.

Researchers have explored several strategies to address this problem. Some approaches involve printing sacrificial materials that can later be removed to leave hollow channels. Others focus on encouraging cells to self-organize into vascular networks after printing. Advances in this area have been impressive, but recreating the full complexity of a human heart’s vasculature remains an unsolved problem.

Electrical Integration and the Rhythm of Life

A functioning heart depends on precisely coordinated electrical signals. Specialized pacemaker cells generate rhythmic impulses that spread through the heart muscle, triggering synchronized contractions. Disruptions to this electrical system can lead to arrhythmias, which can be life-threatening.

In bioprinted cardiac tissue, achieving proper electrical integration is essential. Cardiomyocytes must form gap junctions, specialized connections that allow electrical signals to pass directly from cell to cell. The spatial arrangement of cells influences how these signals propagate, affecting both the speed and direction of conduction.

Experiments with small bioprinted cardiac patches have shown that printed cardiomyocytes can beat spontaneously and even synchronize their contractions. This is an encouraging sign, but scaling this behavior up to a full-sized human heart introduces new challenges. Electrical signals must travel longer distances without degradation, and the overall conduction pattern must mirror that of a natural heart. This level of control is still beyond current capabilities, but ongoing research continues to push the boundary.

Mechanical Forces and the Physics of the Beating Heart

The heart is not only an electrical organ but a mechanical one. With each beat, it generates force to propel blood through the circulatory system. This mechanical work places significant stress on cardiac tissue. Any printed heart must be able to withstand these forces over billions of cycles.

From a physics perspective, this requires careful matching of material properties to biological function. The elasticity, tensile strength, and fatigue resistance of printed tissue must fall within narrow ranges. If the tissue is too weak, it will fail under load. If it is too rigid, it will not contract efficiently.

Moreover, mechanical forces influence cell behavior. Cardiomyocytes respond to stretching and compression by altering gene expression and protein synthesis. This phenomenon, known as mechanotransduction, means that the physical environment of the printed heart will shape its biological development. Successful bioprinting must therefore consider not only static structure but dynamic mechanical cues that guide tissue maturation.

Stem Cells and the Promise of Personalization

One of the most hopeful aspects of heart bioprinting lies in the use of stem cells. Induced pluripotent stem cells can be derived from a patient’s own tissues and then coaxed to become cardiomyocytes or other cardiac cell types. In principle, this allows for the creation of personalized heart tissue that the patient’s immune system is less likely to reject.

This personalization addresses one of the major limitations of traditional organ transplantation: immune rejection. Even with careful matching and immunosuppressive drugs, transplanted organs carry long-term risks. A bioprinted heart made from a patient’s own cells could dramatically reduce these risks.

However, stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes often resemble immature heart cells rather than fully adult ones. They may beat irregularly or lack the strength of mature tissue. Encouraging these cells to fully mature remains an active area of research, involving biochemical signals, electrical stimulation, and mechanical conditioning.

Current Achievements and Their Limits

Despite the immense challenges, progress in 3D bioprinting has been remarkable. Researchers have successfully printed small patches of cardiac tissue that can contract rhythmically. Miniature heart-like structures, sometimes referred to as cardiac organoids, have been created to study disease and drug responses. These models have already proven valuable for research, reducing reliance on animal experiments and providing insights into human-specific biology.

However, these successes should not be mistaken for the printing of a fully functional human heart. Current printed tissues are far smaller, simpler, and less robust than the real organ. They lack fully developed vasculature, mature cell populations, and the integrated structure required for transplantation. The gap between laboratory demonstrations and clinical reality remains substantial.

Recognizing this gap is not a sign of pessimism but of scientific honesty. Each advance builds foundational knowledge that will be essential for future breakthroughs. Bioprinting a human heart is not a single problem but a constellation of interconnected challenges, each requiring sustained effort.

Ethical and Philosophical Dimensions

The idea of printing a human heart inevitably raises ethical questions. If we can create living organs, how should they be regulated? Who owns the printed tissue? How do we ensure equitable access to such advanced therapies? These questions are not obstacles to progress but essential companions to it.

There is also a deeper philosophical dimension. Bioprinting blurs the line between what is grown and what is made. A printed heart is both engineered and alive. This challenges traditional distinctions between artificial and natural, forcing society to rethink its relationship with technology and biology.

Importantly, ethical discussions must be grounded in accurate science. Sensationalism can distort public understanding and undermine trust. Clear communication about what bioprinting can and cannot currently achieve is essential for informed debate.

The Road Ahead: Incremental Progress, Profound Impact

The question of whether we can print a functioning human heart does not have a simple yes or no answer. From a scientific standpoint, there is no fundamental law of physics or biology that forbids it. The heart operates according to principles that, in theory, can be understood and replicated. Yet the practical challenges are immense, and the timeline is uncertain.

Progress is likely to be incremental. Before whole hearts can be printed, partial solutions will emerge. Bioprinted cardiac patches may be used to repair damaged areas after heart attacks. Improved organoids will advance drug testing and disease modeling. Hybrid approaches combining bioprinting with existing medical devices may offer new therapies.

Each of these steps carries profound implications for medicine and human health. Even if the ultimate goal of printing a full human heart remains decades away, the journey toward it is already transforming science.

A New Relationship Between Life and Technology

3D bioprinting represents more than a technological innovation. It signals a new relationship between humanity and living systems. Instead of merely observing or repairing the body, we are beginning to imagine building it in precise and deliberate ways.

This vision is both exhilarating and humbling. It reminds us of the extraordinary complexity of life and the responsibility that comes with attempting to recreate it. The heart, with its relentless rhythm and symbolic weight, stands as the ultimate test of this ambition.

Whether or not a fully functioning printed human heart becomes a clinical reality in the near future, the pursuit itself is reshaping our understanding of biology, physics, and medicine. It challenges scientists to integrate disciplines, to respect the subtleties of living systems, and to approach creation with care as well as creativity.

Conclusion: Can We Print a Functioning Human Heart?

The honest scientific answer is that we cannot yet print a fully functioning human heart, but we are no longer asking an impossible question. What once belonged solely to imagination has entered the realm of serious research. Through advances in bioprinting, stem cell biology, materials science, and physics, the outlines of a solution are slowly taking shape.

The heart has always been a symbol of life’s resilience and vulnerability. In striving to print it, scientists are not attempting to replace nature but to learn from it at the deepest level. The effort reflects humanity’s enduring desire to heal, to understand, and to push the boundaries of what is possible.

In this sense, 3D bioprinting is not just about printing organs. It is about redefining the future of medicine and our relationship with life itself. The printed heart, whether realized tomorrow or decades from now, stands as a testament to human curiosity and the belief that even the most complex mysteries can, one day, be understood.