On a clear night, when the lights of cities fall away and the sky reveals its true depth, the universe appears vast beyond comprehension. Stars scatter across the darkness, galaxies glow faintly in telescopes, and the sense of scale stretches the human mind to its limits. Yet even this overwhelming immensity raises a deeper question that has haunted thinkers for centuries: does the universe go on forever, or does it have an edge? Is the cosmos truly infinite, or is it merely staggeringly large, far beyond anything we can directly observe?

This question is not only poetic or philosophical. It lies at the heart of modern cosmology, the scientific study of the universe as a whole. Advances in physics, astronomy, and mathematics have transformed this ancient puzzle into a precise scientific inquiry. By examining the geometry of space, the behavior of light, and the expansion of the cosmos, scientists are gradually uncovering clues about the ultimate size and shape of reality. Yet despite remarkable progress, the answer remains one of the most profound and challenging mysteries in science.

Why the Question of Infinity Matters

At first glance, whether the universe is infinite or finite might seem like an abstract curiosity with little practical relevance. Yet the implications are immense. The size and shape of the universe determine how matter is distributed, how galaxies form, and how cosmic history unfolds. They influence the ultimate fate of the cosmos and shape our understanding of fundamental physical laws.

If the universe is infinite, then every physically possible configuration of matter may occur somewhere, no matter how improbable. In such a cosmos, distant regions could mirror our own, perhaps even containing galaxies, stars, or planetary systems remarkably similar to those we observe nearby. If the universe is finite, on the other hand, it possesses a total volume and possibly a global structure that constrains what can exist and how cosmic evolution proceeds.

Beyond physics, the question also touches something deeply human. An infinite universe challenges our sense of uniqueness and scale, while a finite universe raises the haunting idea of boundaries, even if those boundaries are unreachable. In either case, the inquiry forces us to confront the limits of knowledge and the place of humanity within a cosmos that vastly exceeds everyday experience.

The Observable Universe and Its Limits

One of the first distinctions cosmologists make is between the observable universe and the universe as a whole. The observable universe is defined not by physical boundaries, but by time and light. Because the universe has a finite age, approximately 13.8 billion years, light from regions beyond a certain distance has not yet had time to reach us. As a result, there exists a spherical region around Earth from which information can be observed today.

This observable universe has a radius of about 46 billion light-years, larger than the universe’s age might suggest because space itself has been expanding while light traveled through it. Within this vast region lie hundreds of billions of galaxies, each containing billions of stars. Yet this immense volume may represent only a fraction of the total cosmos.

Crucially, the observable universe does not define the size of the universe itself. Beyond the horizon of observation may lie regions that are forever inaccessible to us, not because they do not exist, but because the expansion of space prevents their light from ever reaching Earth. Thus, even with perfect instruments, our view of the cosmos is fundamentally limited.

Expansion Does Not Require an Edge

A common misconception is that if the universe is expanding, it must be expanding into something. This intuitive picture imagines galaxies moving outward from a central point into empty space. Modern cosmology, however, describes expansion very differently. Space itself is stretching, increasing the distance between galaxies without requiring an external space into which the universe expands.

An often-used analogy is the surface of a balloon being inflated. As the balloon expands, every point on its surface moves away from every other point, yet the surface itself has no center and no edge. Importantly, this two-dimensional surface is finite in area but unbounded; one can travel indefinitely without encountering a boundary.

This analogy illustrates a key idea: a universe can be finite without having an edge. Similarly, the three-dimensional universe we inhabit could be finite yet unbounded, meaning that traveling far enough in a straight line might eventually bring one back to the starting point, though the distances involved could be unimaginably large.

Geometry as the Key to Cosmic Size

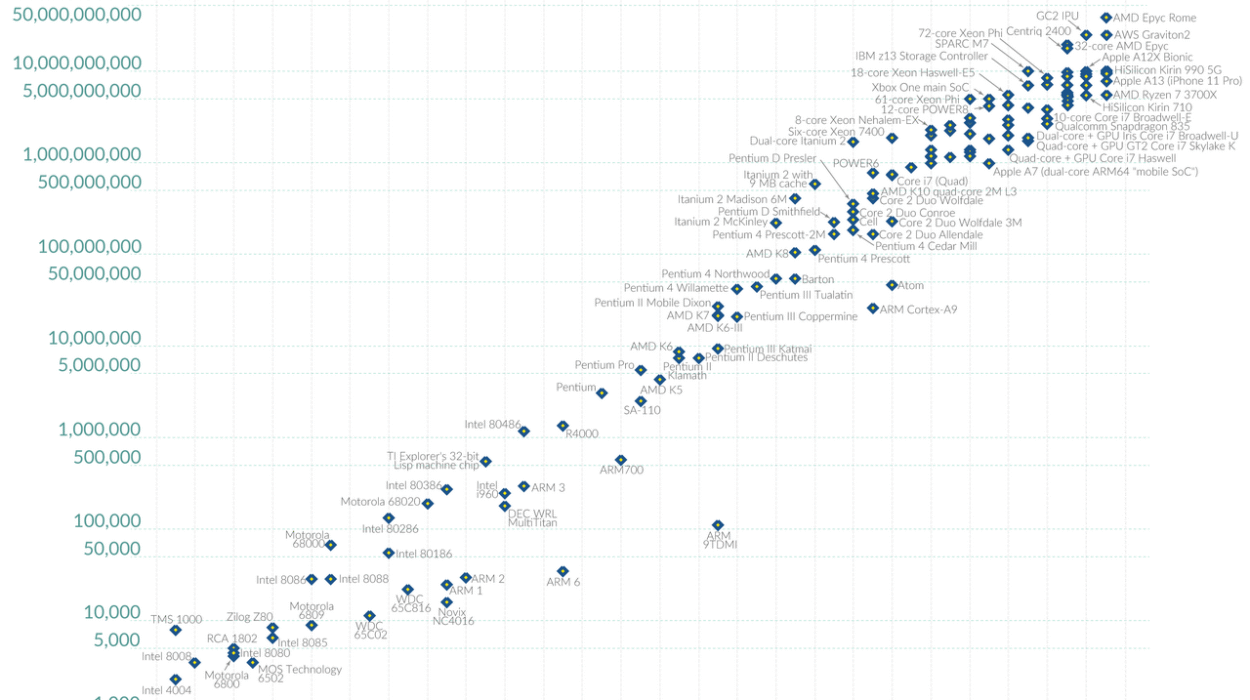

In modern cosmology, the question of whether the universe is infinite or finite is closely tied to its geometry. According to general relativity, the distribution of matter and energy determines the curvature of space. This curvature, in turn, affects the overall shape and extent of the universe.

There are three broad possibilities for cosmic geometry. In a positively curved universe, space resembles the three-dimensional analogue of a sphere. Such a universe is finite in volume but has no boundary. In a negatively curved universe, space has a saddle-like geometry and extends infinitely. In a flat universe, space follows the familiar rules of Euclidean geometry and may be either infinite or finite, depending on its global topology.

Measurements of the cosmic microwave background radiation, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang, have provided precise data on cosmic geometry. These observations strongly indicate that the universe is very close to flat. However, “close to flat” does not necessarily mean infinite. A flat universe could still be finite if space wraps around itself in a more complex way than simple curvature suggests.

The Cosmic Microwave Background as a Map of Space

The cosmic microwave background, often abbreviated as the CMB, is one of the most powerful tools for probing the structure of the universe. This radiation originated when the universe was about 380,000 years old, at a time when atoms first formed and light could travel freely through space. Today, it fills the cosmos almost uniformly, with tiny temperature variations that encode information about early cosmic conditions.

By studying the size and distribution of these variations, cosmologists can infer the geometry of space. The observed patterns match the predictions of a nearly flat universe with remarkable precision. This finding suggests that, on the largest scales we can observe, space does not exhibit strong curvature.

However, the CMB only provides information about the observable universe. If the universe extends far beyond this region, its global shape could still be finite or infinite without leaving an obvious imprint on the observable portion. Thus, while the CMB offers crucial evidence, it does not settle the question definitively.

Inflation and the Case for Vastness

One of the most influential ideas in modern cosmology is cosmic inflation, a theory proposing that the universe underwent an extremely rapid expansion in its earliest moments. Inflation was introduced to explain why the universe appears so uniform and flat on large scales.

According to inflationary theory, a tiny region of space expanded exponentially, smoothing out irregularities and driving the geometry toward flatness. If inflation occurred, it likely produced a universe far larger than the observable region, potentially many orders of magnitude larger.

Some versions of inflation suggest that the universe may be infinite, or at least so vast that any curvature or global structure is undetectable within our observable horizon. Other versions allow for a finite universe, but one so enormous that its finiteness has no practical observational consequences. Inflation thus strengthens the case that the universe is, at minimum, “really, really big.”

Topology: The Shape Beyond Geometry

While geometry describes local curvature, topology concerns the global connectivity of space. Two spaces can share the same local geometry yet differ dramatically in overall shape. For example, a flat sheet of paper and the surface of a cylinder are locally flat, but their global structures differ.

In cosmology, this means that even if the universe is geometrically flat, it could still be finite if space wraps around itself in certain ways. Light traveling through such a universe could, in principle, return from different directions, producing repeating patterns in the sky.

Scientists have searched for such signatures in the cosmic microwave background, looking for matching circles or repeated features that would indicate a finite topology. So far, no definitive evidence of this kind has been found. However, the absence of evidence does not rule out a finite universe; it may simply be larger than our observational reach.

Infinity in Physics and Mathematics

The concept of infinity occupies a strange position in physics. In mathematics, infinity is a well-defined and rigorously handled concept. In physics, however, infinities often signal the breakdown of a theory rather than a physical reality.

Many physicists are cautious about invoking actual infinities in nature. In theories of gravity and quantum mechanics, infinities frequently arise when models are pushed beyond their valid domains. This has led some scientists to suspect that the universe may be finite, even if extraordinarily large.

Yet caution alone does not constitute evidence. Current physical theories do not forbid an infinite universe, and some models naturally lead to infinite spatial extent. Whether nature truly realizes infinity or merely approaches it remains an open question, one that challenges both observation and theory.

The Multiverse and Radical Possibilities

Some modern theories propose that our universe may be just one region within a much larger multiverse. In certain inflationary models, inflation never completely ends, producing an endless collection of bubble universes with varying physical properties.

In such scenarios, the total multiverse could be infinite, even if individual universes within it are finite. Our observable universe would then be a small part of a far grander cosmic structure. While intriguing, these ideas are highly speculative and currently lack direct observational support.

The multiverse concept illustrates how questions about cosmic size can intersect with the deepest issues in theoretical physics. It also highlights the challenge of testing ideas that may lie beyond any possible observation, raising important questions about the nature of scientific explanation.

The Role of Observation and Its Limits

Science advances through observation and experiment, yet cosmology confronts unique limitations. We cannot step outside the universe to view it from afar, nor can we access regions beyond the cosmic horizon. As a result, certain questions may remain permanently underdetermined by data.

Nevertheless, physicists continue to push observational boundaries. Improved measurements of cosmic background radiation, large-scale galaxy surveys, and studies of gravitational waves all refine our understanding of cosmic structure. Each new dataset narrows the range of plausible models, even if it does not deliver a final answer.

The question of infinity may ultimately hinge on indirect evidence and theoretical consistency rather than direct measurement. In this sense, cosmology occupies a frontier where empirical science and philosophical reasoning intertwine.

Human Intuition and Cosmic Scale

The difficulty of grasping the universe’s size is not merely technical; it is psychological. Human intuition evolved to navigate environments measured in meters and kilometers, not light-years and cosmic horizons. Concepts such as infinite space or curved geometry stretch the imagination to its limits.

Yet the history of science shows that intuition can be reshaped by understanding. Ideas that once seemed absurd, such as Earth orbiting the Sun or time flowing at different rates for different observers, have become accepted through evidence and reasoning. Similarly, the true scale of the universe, whether finite or infinite, may one day feel less alien as knowledge deepens.

Engaging with this question invites humility. It reminds us that the universe is under no obligation to conform to human expectations, and that our role is to listen carefully to what nature reveals.

The Emotional Weight of Infinity

Beyond equations and observations, the idea of an infinite universe carries emotional resonance. For some, infinity evokes awe and freedom, a cosmos without boundaries where exploration has no end. For others, it inspires unease, suggesting a reality so vast that individual lives seem vanishingly small.

A finite universe, by contrast, can feel more intimate, a complete and self-contained whole. Yet finiteness does not make the cosmos any less mysterious. A universe with a total volume and shape still raises questions about why it exists in that form and not another.

These emotional responses are not distractions from science; they are part of the human engagement with it. They motivate inquiry and shape the questions we ask, even as scientific methods strive for objectivity.

What We Can Say with Confidence

Despite the uncertainties, some conclusions are firmly supported by evidence. The universe is far larger than the observable region alone might suggest. It has been expanding for billions of years from an early hot, dense state. On the largest observable scales, space appears remarkably uniform and nearly flat.

Whether the universe is infinite or finite remains unresolved. Current data are consistent with both possibilities, provided the universe is sufficiently large. The distinction may lie beyond observational reach, at least with present technology and understanding.

This uncertainty is not a failure of science, but a reflection of its honesty. Physics advances by clearly distinguishing between what is known, what is plausible, and what remains speculative.

The Question That Endures

“Is the universe infinite or just really, really big?” endures because it sits at the boundary of knowledge. It combines precise measurement with deep abstraction, empirical data with philosophical reflection. It reminds us that even as science explains more of the cosmos, some questions resist final answers.

Perhaps future discoveries will reveal subtle signatures of cosmic finiteness or provide compelling theoretical reasons to favor infinity. Perhaps the question will remain open, a reminder of the limits imposed by light, time, and human perspective.

In confronting this mystery, physics does more than describe the universe. It invites us to expand our imagination, to accept uncertainty, and to find meaning in the pursuit of understanding itself. Whether infinite or finite, the universe remains an extraordinary place, one that continues to challenge and inspire the human mind.