On clear nights, when the sky is far from city lights, the universe appears generous. Thousands of stars scatter across the darkness, the Milky Way stretches like a pale river of light, and distant galaxies reveal themselves as faint smudges. To the human eye, this spectacle feels vast and complete. Yet this visible universe, luminous and seemingly abundant, represents only a small fraction of what actually exists. Modern physics tells us that everything we can see—stars, planets, gas clouds, dust, and even our own bodies—accounts for barely fifteen percent of the matter in the universe. The remaining eighty-five percent is something profoundly strange: dark matter, an invisible substance that neither emits nor absorbs light, yet dominates the cosmic landscape.

The mystery of dark matter is one of the most compelling scientific puzzles of our time. It challenges our understanding of matter, gravity, and the very structure of the universe. Dark matter does not announce itself through light or heat. It does not glow, sparkle, or cast shadows. Instead, its presence is inferred through its gravitational influence, shaping galaxies, guiding cosmic evolution, and holding together structures that would otherwise fly apart. To ask why we cannot see eighty-five percent of the universe is to confront the limits of human perception and to explore how science uncovers reality beyond what our senses reveal.

The Birth of a Cosmic Puzzle

The story of dark matter begins not with exotic particles or futuristic detectors, but with careful observation and an unsettling discrepancy. In the early twentieth century, astronomers began to measure the motions of stars within galaxies and galaxies within clusters. According to Newtonian gravity and later Einstein’s theory of general relativity, the speed at which objects move under gravity depends on the amount of mass present. More mass means stronger gravity and faster motion.

When astronomers examined galaxy clusters, they found that the visible matter—stars and hot gas—was insufficient to account for the observed motions. Galaxies were moving too fast, as if an unseen mass were exerting additional gravitational pull. In the 1930s, the Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky studied the Coma Cluster of galaxies and concluded that a large amount of unseen matter must be present. He called it “dunkle Materie,” or dark matter. At the time, his claim was largely overlooked, partly because it challenged existing assumptions and partly because the observational data were limited.

Decades later, the problem resurfaced with greater clarity. In the 1970s, astronomer Vera Rubin and her collaborators measured how stars orbit around the centers of spiral galaxies. They expected that stars farther from the galactic center would move more slowly, much as planets farther from the Sun orbit at lower speeds. Instead, they found that stars maintained nearly constant speeds even at great distances from the galactic core. This flat rotation curve implied that galaxies are embedded in massive halos of invisible matter, extending far beyond their visible boundaries.

These observations transformed dark matter from a speculative idea into a central problem in astrophysics. The universe, it seemed, was dominated by something we could not see.

Why Light Fails Us

To understand why dark matter is invisible, it is essential to consider how we see anything at all. Vision, whether human or instrumental, depends on electromagnetic radiation. Objects become visible because they emit light, reflect light, or absorb and re-emit energy at specific wavelengths. Telescopes extend this principle across the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays, revealing phenomena invisible to the naked eye.

Dark matter, however, appears to be fundamentally different. It does not interact with electromagnetic radiation in any detectable way. It neither emits nor absorbs light, nor does it scatter photons. As a result, no telescope, regardless of sophistication, can capture an image of dark matter directly. Its invisibility is not due to distance or obscuration, but to a fundamental absence of electromagnetic interaction.

This property distinguishes dark matter from ordinary matter, which physicists call baryonic matter. Baryonic matter is composed of protons, neutrons, and electrons, particles that interact readily with light and with one another. Dark matter, by contrast, seems to interact primarily through gravity, exerting influence without revealing itself through radiation. This makes it extraordinarily difficult to detect, yet unmistakably present through its gravitational effects.

Gravity as the Cosmic Messenger

Although dark matter cannot be seen, gravity provides a powerful means of detecting its presence. Gravity is universal; it affects all forms of mass and energy, regardless of whether they interact with light. By studying how objects move under gravity, physicists can infer the distribution of mass, including mass that remains invisible.

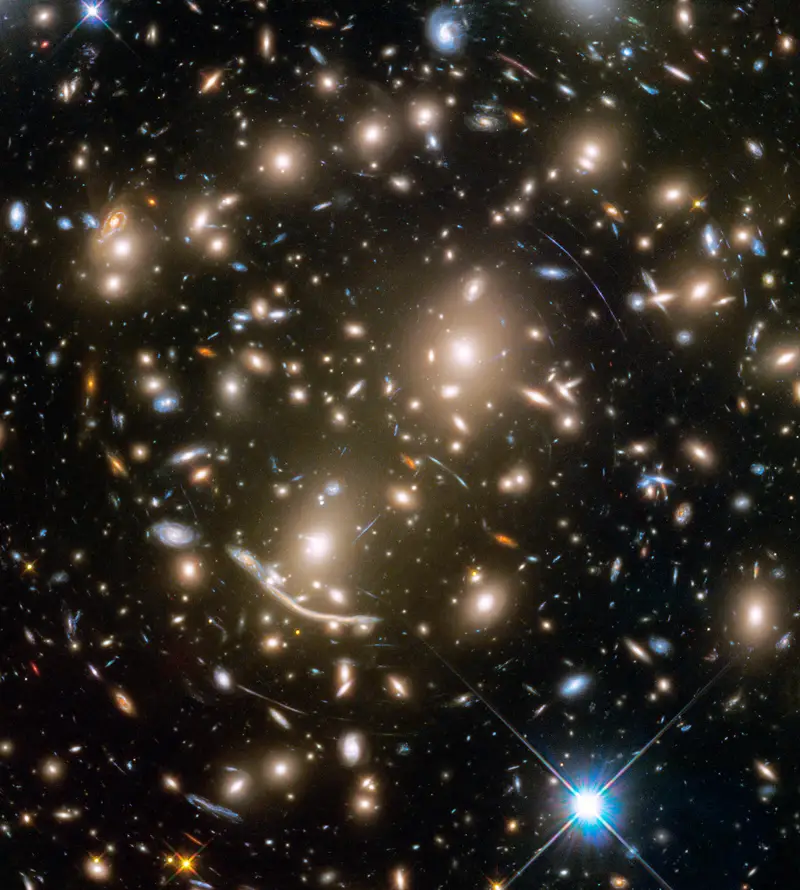

One of the most striking demonstrations of dark matter’s gravitational influence comes from gravitational lensing. According to general relativity, massive objects bend the fabric of spacetime, causing light from distant sources to curve as it passes nearby. This effect can distort, magnify, or multiply the images of background galaxies. By analyzing these distortions, astronomers can map the distribution of mass in the foreground, including dark matter.

Gravitational lensing studies consistently reveal far more mass than can be accounted for by visible matter alone. In some cases, such as collisions between galaxy clusters, lensing maps show that most of the mass is separated from the hot, X-ray-emitting gas that dominates the visible matter. These observations provide compelling evidence that dark matter is a distinct component of the universe, not merely a miscalculation of visible mass.

Gravity also explains why galaxies and galaxy clusters remain bound. Without dark matter, the observed speeds of stars and galaxies would cause them to disperse over cosmic timescales. Dark matter acts as a gravitational scaffold, holding structures together and enabling the formation of galaxies in the first place.

Dark Matter and the Architecture of the Universe

Dark matter is not merely a passive background component; it plays an active role in shaping the universe. In the early universe, shortly after the Big Bang, tiny fluctuations in density served as seeds for structure formation. Dark matter, interacting weakly with radiation, began to clump under gravity earlier than ordinary matter, which was tightly coupled to photons at that time.

As dark matter clumped, it formed gravitational wells into which ordinary matter eventually fell. Gas cooled and condensed within these wells, leading to the formation of stars and galaxies. In this sense, dark matter provided the blueprint for the cosmic web, the vast network of filaments and voids that characterizes the large-scale structure of the universe.

Computer simulations that include dark matter reproduce the observed distribution of galaxies with remarkable accuracy. Without dark matter, these simulations fail to generate the structures we see today. This success strengthens the case for dark matter as an essential component of cosmology, deeply intertwined with the history of the universe.

What Dark Matter Is Not

Understanding dark matter requires not only proposing what it might be, but also ruling out what it cannot be. One might imagine that dark matter consists of ordinary matter that is simply too faint to detect, such as dim stars, planets, or cold gas. However, careful observations constrain the amount of baryonic matter in the universe, based on measurements of cosmic microwave background radiation and the abundances of light elements formed in the early universe.

These measurements indicate that baryonic matter makes up only a small fraction of the total matter content. There simply is not enough ordinary matter, visible or invisible, to account for the gravitational effects attributed to dark matter. This implies that dark matter must be fundamentally different from the matter that composes stars and planets.

Dark matter is also not antimatter. Although antimatter annihilates with matter and emits energy, such annihilations are not observed at the levels required to explain dark matter. Nor can dark matter be explained by modifications to gravity alone, at least not in a way that accounts for all observations consistently. While alternative theories of gravity have been proposed, the dark matter hypothesis remains the most successful framework for explaining a wide range of phenomena.

The Leading Candidates for Dark Matter

If dark matter is not made of ordinary particles, what could it be? Physicists have proposed several candidates, guided by both theoretical considerations and experimental constraints. One prominent class of candidates consists of weakly interacting massive particles, often referred to as WIMPs. These hypothetical particles would interact through gravity and possibly the weak nuclear force, making them difficult to detect but capable of producing the observed dark matter abundance.

Another compelling candidate arises from attempts to solve unrelated problems in particle physics. Axions, originally proposed to address a symmetry issue in the strong nuclear force, could also serve as dark matter particles. They would be extremely light and interact very weakly with ordinary matter, making them challenging to detect but potentially abundant.

Other possibilities include sterile neutrinos, particles that interact even more weakly than known neutrinos, and more exotic entities emerging from theories that extend beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. Each candidate reflects a different approach to understanding physics at a fundamental level, illustrating how the dark matter problem connects cosmology with particle physics.

The Global Search for the Invisible

The search for dark matter is one of the most ambitious experimental efforts in modern science. Physicists employ multiple strategies, each designed to detect dark matter in a different way. Direct detection experiments aim to observe rare interactions between dark matter particles and ordinary matter. These experiments are typically located deep underground, shielded from cosmic rays and other sources of background noise.

Indirect detection experiments look for the products of dark matter annihilation or decay, such as high-energy photons or neutrinos, emanating from regions where dark matter is thought to be dense. Meanwhile, particle accelerators attempt to create dark matter particles in high-energy collisions, inferring their existence from missing energy and momentum.

Despite decades of effort, dark matter has not yet been directly detected. This absence of definitive evidence has not discouraged researchers; rather, it has refined theoretical models and experimental techniques. Each null result narrows the range of possibilities, bringing scientists closer to understanding what dark matter can and cannot be.

The Emotional Weight of the Unknown

The mystery of dark matter is not merely technical; it carries an emotional resonance that speaks to the human experience of confronting the unknown. There is something profoundly humbling about realizing that most of the universe is invisible and unfamiliar. Dark matter reminds us that reality extends far beyond what we can perceive, that the cosmos harbors secrets that resist easy explanation.

At the same time, this mystery is a source of inspiration. It exemplifies the power of scientific reasoning to reveal unseen aspects of nature through indirect evidence and careful inference. Even without seeing dark matter directly, physicists have built a coherent and predictive framework that explains its effects with remarkable precision.

This tension between ignorance and understanding lies at the heart of scientific progress. Dark matter represents both a failure of current knowledge and a promise of future discovery. It challenges scientists to develop new theories, invent new instruments, and rethink fundamental assumptions about matter and forces.

Dark Matter and the Nature of Reality

The existence of dark matter forces us to reconsider what it means for something to be real. In everyday language, reality is often equated with visibility or tangibility. Yet physics has long shown that many real phenomena, from electromagnetic fields to subatomic particles, are not directly observable. Dark matter extends this lesson to cosmic scales, demonstrating that the universe is shaped by entities that elude direct detection.

This realization has philosophical implications. It suggests that human perception captures only a narrow slice of reality, and that scientific knowledge expands this slice through abstract reasoning and empirical evidence. Dark matter exemplifies how science transcends sensory experience, revealing layers of existence that are accessible only through careful analysis.

In this sense, dark matter is not an anomaly but a continuation of a long tradition in physics. From atoms to quarks, from spacetime curvature to quantum fields, the history of physics is a story of uncovering invisible structures that underlie the visible world.

The Interplay Between Dark Matter and Dark Energy

Although dark matter dominates the mass of the universe, it is not the largest component of the cosmic energy budget. Dark energy, an even more mysterious entity, appears to drive the accelerated expansion of the universe. Together, dark matter and dark energy constitute the vast majority of the cosmos, rendering ordinary matter a minor player on the cosmic stage.

The relationship between dark matter and dark energy remains poorly understood. Dark matter clumps and structures the universe, while dark energy acts as a kind of cosmic repulsion, influencing its large-scale dynamics. Understanding how these components interact, if at all, is one of the central challenges of modern cosmology.

The dominance of these unseen components underscores how incomplete our picture of the universe remains. It also highlights the remarkable progress that has been made, as scientists have inferred the existence and properties of these entities through precise observations and theoretical insight.

Why the Mystery Endures

The persistence of the dark matter mystery reflects both the difficulty of the problem and the rigor of scientific standards. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and physicists are cautious about declaring success without unambiguous data. The universe does not yield its secrets easily, and dark matter, by its very nature, resists direct scrutiny.

Yet the absence of direct detection does not imply failure. On the contrary, it testifies to the subtlety of the universe and the sophistication of modern science. Each experiment, whether it finds a signal or not, contributes valuable information. The search for dark matter is a process of elimination and refinement, guided by theory and constrained by observation.

As technology advances and new ideas emerge, the prospects for discovery continue to grow. Future experiments may finally reveal the particles that constitute dark matter, or they may uncover entirely new principles that reshape our understanding of gravity and matter.

A Universe More Mysterious Than Imagined

The realization that eighty-five percent of the universe is invisible challenges our sense of completeness. It suggests that the cosmos we see is only a surface layer, beneath which lies a vast and hidden structure. Dark matter is a reminder that nature is deeper and stranger than it first appears, that even the most familiar cosmic scenes are shaped by unseen forces.

This mystery does not diminish the beauty of the universe; it enhances it. Knowing that galaxies are sculpted by invisible halos, that cosmic structures emerge from hidden scaffolding, adds a layer of wonder to the night sky. The stars become not only points of light, but tracers of an unseen architecture.

In confronting the mystery of dark matter, humanity stands at the edge of knowledge, gazing into the unknown with curiosity and determination. The inability to see most of the universe is not a limitation to be lamented, but an invitation to explore. Dark matter represents the frontier of physics, a challenge that promises to deepen our understanding of reality and our place within it.