Meteor showers feel familiar. We make wishes, lie on rooftops, and watch streaks of light tear briefly across the sky. They appear romantic, fleeting, almost magical. But beneath that beauty lies a story far richer, stranger, and more scientifically profound than most people realize. Meteor showers are not random fireworks of the universe; they are ancient messages, dynamic processes, and living records of our solar system’s history.

Here are ten scientifically accurate, deeply fascinating things about meteor showers that most people don’t know—and once you do, you may never look at a shooting star the same way again.

1. Meteor Showers Are Cosmic Debris Trails, Not Random Events

It’s easy to think of meteor showers as spontaneous sky spectacles, but in reality they are anything but random. Every major meteor shower occurs because Earth passes through a stream of debris left behind by a comet or, in some cases, an asteroid. These debris streams are called meteoroid streams, and they behave like invisible rivers flowing through space.

As a comet travels around the Sun, heat causes its icy surface to sublimate—turning directly from solid to gas. This process releases dust, rock fragments, and organic compounds that spread out along the comet’s orbit. Over centuries or even millennia, these particles form a long, thin trail that can stretch millions of kilometers.

When Earth’s orbit intersects one of these trails, gravity pulls the particles into our atmosphere at high speed. The result is a meteor shower. The reason the shower happens at roughly the same time each year is because Earth crosses the same region of space annually, like a runner passing the same mile marker on a circular track.

Emotionally, this means every meteor you see is part of an ancient structure, shaped long before modern civilization existed. You are not just watching a light show; you are passing through the fossilized breath of a comet that may have last visited the inner solar system thousands of years ago.

2. The Meteors You See Are Smaller Than You Think

Those brilliant streaks blazing across the sky feel massive and powerful, but most meteors are shockingly small. Many are no larger than a grain of sand. Even the brightest meteors you see during a shower—called fireballs—are often only the size of a marble or pebble.

What creates the dramatic flash is not size, but speed. Meteoroids enter Earth’s atmosphere at velocities ranging from about 11 kilometers per second to over 70 kilometers per second. At those speeds, friction with atmospheric gases generates intense heat, causing the meteoroid to vaporize almost instantly. The glowing trail you see is actually superheated air and ionized particles, not the solid object itself.

This realization reshapes the emotional experience of meteor watching. Something infinitesimally small can produce something breathtakingly beautiful. It’s a reminder that impact is not always about mass or permanence, but about energy and motion—an idea that echoes far beyond astronomy.

3. Meteor Showers Have “Radiant Points” Because of Perspective, Not Origin

If you watch a meteor shower long enough, you may notice that the meteors appear to radiate from a single point in the sky. This point is known as the radiant, and it gives each meteor shower its name. The Perseids radiate from Perseus, the Leonids from Leo, and so on.

But here’s the lesser-known truth: the meteors are not actually originating from that point. The radiant is an illusion of perspective, similar to how parallel railroad tracks appear to converge in the distance.

All the meteoroids in a shower are traveling through space on nearly parallel paths. As Earth plows into the stream, those parallel paths appear to diverge from a single point when projected onto the dome of the sky. If you trace each meteor backward, they all seem to meet at the radiant.

Understanding this adds a layer of depth to meteor watching. You’re witnessing geometry on a cosmic scale, where motion, speed, and perspective conspire to paint a false center in the heavens. The sky, it turns out, is not just a stage—it’s a canvas shaped by perception.

4. Meteor Showers Change Over Time—They Are Not Eternal

It may feel like meteor showers are timeless, but they are actually temporary phenomena on astronomical timescales. Meteoroid streams disperse over time due to gravitational interactions with planets, radiation pressure from sunlight, and collisions between particles.

Some meteor showers that were spectacular in the past are now faint or nearly extinct. Others have intensified because Earth’s orbit has shifted slightly, or because the parent comet recently replenished the debris stream. The Leonid meteor shower, for example, is famous for producing meteor storms—bursts of thousands of meteors per hour—but only during certain years when Earth passes through particularly dense filaments of debris.

This impermanence carries emotional weight. When you watch a meteor shower, you are participating in a temporary alignment of cosmic circumstances. Some of the most intense showers in history may never occur again, while future generations may witness displays we cannot yet imagine.

Meteor showers remind us that even celestial rhythms are subject to change. The universe is not static; it is alive with motion, decay, and renewal.

5. Some Meteor Showers Come From Asteroids, Not Comets

For a long time, astronomers believed that all meteor showers originated from comets. While comets are indeed the most common source, modern research has revealed that some showers are linked to asteroids—objects traditionally thought of as inert, rocky bodies.

Certain asteroids, especially those with elongated orbits, can shed material through collisions or thermal fracturing as they approach the Sun. These debris clouds can form meteoroid streams similar to those produced by comets. One famous example is the Geminid meteor shower, which originates from an object called 3200 Phaethon. Phaethon behaves like a hybrid, showing characteristics of both asteroids and comets.

This blurring of categories has deep scientific implications. It suggests that the distinction between comets and asteroids is not as clear-cut as once believed. The solar system is full of transitional objects that challenge our classifications.

Emotionally, this discovery reshapes the narrative of meteor showers. They are not just the dying breath of icy wanderers; they are also the result of rocky bodies breaking down under solar stress. Even the most seemingly solid things in the cosmos are subject to erosion and change.

6. Meteor Showers Help Scientists Study the Early Solar System

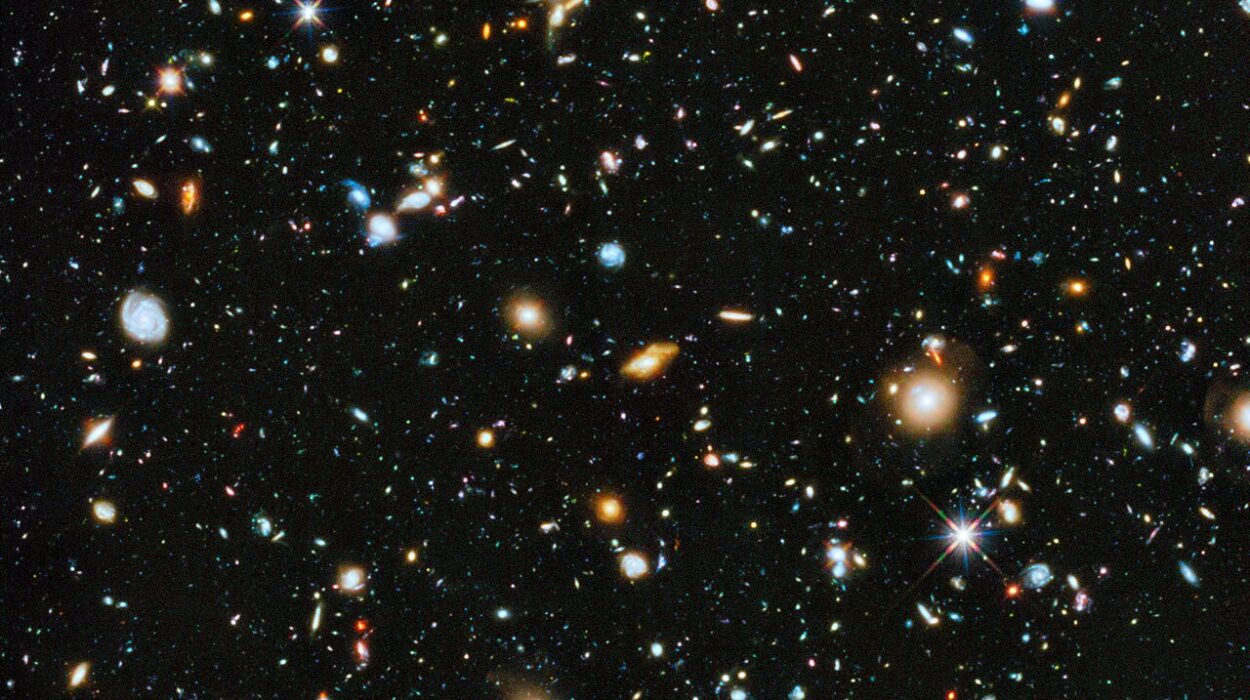

Meteor showers are not just beautiful; they are scientifically invaluable. The particles that burn up in our atmosphere are remnants of the early solar system, preserved in the cold vacuum of space for billions of years.

By studying meteoroids—especially those that survive atmospheric entry and become meteorites—scientists gain insight into the chemical composition, structure, and age of primordial material. Spectroscopic analysis of meteors as they burn reveals the presence of elements like iron, magnesium, sodium, and even complex organic compounds.

Some of the organic molecules detected in meteors are similar to those involved in life on Earth. This supports the idea that meteor impacts may have delivered key ingredients for life to the early Earth, seeding our planet with the building blocks of biology.

When you watch a meteor shower, you are witnessing ancient matter returning home. These particles formed alongside the Sun and planets, long before Earth became habitable. Their brief flash in the sky is the final chapter of a story billions of years in the making.

7. Not All Meteor Showers Are Visible Everywhere on Earth

Meteor showers are global events, but visibility depends heavily on location, timing, and geometry. The radiant of a meteor shower must be above the horizon for meteors to be visible, which means some showers favor the Northern Hemisphere, others the Southern Hemisphere.

Latitude plays a major role. Showers with radiants near the celestial equator are visible from much of the world, while those near the celestial poles may be inaccessible to half the planet. Time of night also matters. Early evening hours often produce fewer meteors because the observer’s location is facing away from Earth’s direction of motion. After midnight, the observer is on the “leading edge” of Earth, directly plowing into the meteoroid stream.

This uneven visibility gives meteor showers a personal, almost intimate quality. A spectacular display for one observer may be completely invisible to another thousands of kilometers away. The universe offers different gifts to different parts of the Earth, reminding us that perspective shapes experience.

8. Meteor Showers Can Create Sounds—But Not the Way You Think

Most meteors burn up tens of kilometers above Earth’s surface, far too high for sound waves to reach the ground before the meteor is gone. Yet for centuries, observers have reported hearing hissing, crackling, or popping sounds simultaneously with bright meteors.

For a long time, these reports were dismissed as imagination. But modern research suggests that some meteors can produce electromagnetic effects that interact with objects near the observer—such as hair, glasses, or dry leaves—causing them to vibrate and generate sound locally. These are known as electrophonic sounds.

This phenomenon is rare and not fully understood, but it highlights how meteor showers can affect Earth in subtle, unexpected ways. They are not just distant spectacles; under the right conditions, they can reach out and touch the senses directly.

Emotionally, the idea that a meteor can be heard as well as seen adds an almost supernatural dimension. It collapses the distance between sky and Earth, making the experience more intimate and immediate.

9. Meteor Showers Can Become Meteor Storms

Most meteor showers produce a modest number of meteors per hour, but under special circumstances, they can erupt into meteor storms—intense outbursts where thousands of meteors streak across the sky in a single hour.

These storms occur when Earth passes through especially dense filaments within a meteoroid stream. Such filaments often originate from relatively recent passages of a parent comet, where fresh material has not yet dispersed.

Historical records describe meteor storms that were so intense they inspired fear, religious fervor, and awe. The Leonid storm of 1833, for example, reportedly filled the sky with falling stars, leading some observers to believe the world was ending. That event played a significant role in the scientific study of meteors, convincing researchers that they were extraterrestrial rather than atmospheric phenomena.

Meteor storms remind us that the sky can still surprise us. Even in an age of satellites and simulations, the universe retains the power to overwhelm human expectation with raw, unfiltered spectacle.

10. Every Meteor Shower Is a Reminder of Earth’s Fragile Shield

One of the most profound truths hidden within meteor showers is what they say about Earth itself. Every meteoroid that burns up harmlessly is stopped by our atmosphere—a thin but powerful shield that protects life on the surface.

Without this atmosphere, even sand-sized particles would strike the ground at cosmic velocities, releasing enormous energy. Over time, such impacts would make the planet hostile to life. Meteor showers demonstrate, again and again, how vital our atmospheric blanket is.

At the same time, meteor showers hint at vulnerability. Larger objects can and do survive atmospheric entry, and Earth’s history includes catastrophic impacts that shaped evolution itself. Meteor showers are the gentle side of a process that, at larger scales, can be destructive.

Emotionally, this duality is striking. The same process that produces beauty also carries danger. The universe is not malicious, but it is indifferent. Our survival depends on delicate balances that physics maintains moment by moment.

A Closing Look at the Sky

Meteor showers are easy to romanticize, but they deserve something deeper than fleeting wishes. They are records of cosmic history, laboratories for science, and emotional bridges between humanity and the universe. Each streak of light is a moment where deep time intersects with human awareness, where something ancient meets something alive.

When you next watch a meteor shower, remember that you are standing inside a moving planet, traveling through a debris field left by a long-gone visitor to the inner solar system. You are seeing the past ignite in the present, briefly, brilliantly, and then vanish.

And in that fleeting moment, the universe is not distant. It is happening right above you.