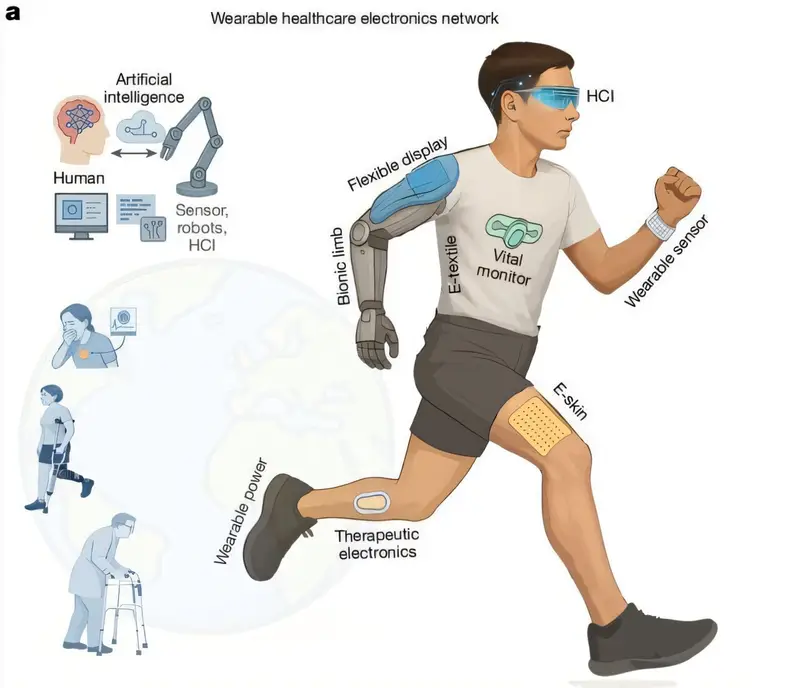

In a world where health is increasingly measured by the silent hum of technology against our skin, a quiet revolution is taking place. From the smartwatches on our wrists to the disposable patches tracking our heartbeats, we are entering an era of “digital infrastructure networks” for the human body. These devices—biophysical and biochemical sensors, e-textiles, and biointegrated therapeutics—offer a level of continuous tracking that was once the stuff of science fiction. But as researchers from the University of Chicago and Cornell University recently discovered, this digital health boom carries a physical weight that the planet is beginning to feel.

The Invisible Weight of a Tiny Patch

At first glance, a continuous glucose monitor or a blood pressure monitor seems insignificant—a feather-light assembly of plastic and silicon. However, when the research team conducted a “cradle-to-grave” life-cycle assessment, they found that these tiny devices have a surprisingly large environmental shadow. A single continuous glucose monitor, for instance, carries a carbon footprint of approximately 2 kg CO2-equivalent. To put that in perspective, using one of these monitors is the environmental equivalent of driving a gasoline-powered car for about five miles.

The researchers looked at four primary anchors of modern wearable tech: the non-invasive continuous glucose monitor, a continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) monitor, a blood pressure monitor, and a point-of-care ultrasound patch. The results showed that per-device warming impacts ranged from 1.06 kg CO2-equivalent for blood pressure tools to a high of 6.11 kg CO2-equivalent for the advanced ultrasound patch. While these numbers might seem small in isolation, the story changes when we look at how we actually use them. Because a glucose monitor is often discarded after just 14 days, the “annualized” impact for a single patient sky-rockets to 50.6 kg CO2-equivalent.

A Torrent of E-Waste on the Horizon

The true scale of the challenge lies in our future. Right now, these devices are becoming essential tools for patients, athletes, and the elderly. The study used diffusion modeling to project where we are headed, and the numbers are staggering: global device consumption is expected to rise 42-fold by 2050. By then, we may be producing nearly 2 billion units every year.

This is the “butterfly effect” of wearable tech. What starts as a small patch in a lab becomes a torrent of 3.4 million metric tons of CO2-equivalent emissions annually. To visualize that, the researchers noted it is roughly equal to the entire carbon footprint of the transportation sector of Chicago. And the problem isn’t just the air we breathe; it’s the land and water, too. The reliance on hazardous chemicals, fossil-based plastics, and critical metals leads to significant ecotoxicity and a mounting pile of e-waste that the current system is not equipped to handle.

Searching for the Source of the Heat

To fix the problem, the scientists had to find the “hotspots”—the specific parts of the device causing the most damage. Using Monte Carlo simulations to account for uncertainty, they traced more than 95% of the impact back to the printed circuit boards and the semiconductors. The culprits aren’t just the materials themselves, but the massive amounts of energy required to purify raw materials and power the high-tech manufacturing processes.

The analysis identified flexible printed circuit board assemblies as the heart of the environmental crisis. Inside these boards, the use of gold in integrated circuits, along with silicon wafers, polyimide, and batteries, creates a concentrated pocket of environmental cost. Even as artificial intelligence drives more efficient data processing, the advanced digital infrastructure required to support these devices only further enlarges their eco-footprint.

Designing a Greener Pulse for the Future

If the problem is rooted in design, then the solution must be as well. The researchers modeled four potential paths toward a more sustainable future, and the results were eye-opening. While switching to biodegradable or recyclable plastics (like starch, cellulose, or polylactic acid) sounds promising, it only reduced the warming impact by a meager 1.8% to 2.6%. Because the circuit boards are so dominant, simply changing the plastic shell isn’t enough.

The real “levers” for change lie in deeper engineering choices. By substituting gold with more common metals like silver, copper, or aluminum, researchers found they could slash warming impacts by 30% and reduce freshwater ecotoxicity and human toxicity by more than 60%. Another breakthrough strategy involves modular designs. By using pluggable interfaces, patients could reuse the expensive, long-lived internal circuits while only replacing the high-turnover, disposable parts. This single change could reduce the warming impact per use by up to 62.4%.

Why This Research Matters

This study serves as a vital wake-up call for the “next generation” of medical technology. It proves that while “greening” the power grid with renewable energy can cut emissions by about half, it does almost nothing to solve the problems of water consumption or toxic chemical runoff.

The significance of this work lies in its call for systems engineering. By linking life-cycle assessments with adoption growth forecasts, we can identify “sustainability blind spots” before they become global crises. As we move toward a world where two billion health monitors are sold annually, this research provides the blueprint for ecologically responsible innovation, ensuring that the technology we use to save human lives does not end up costing us the health of the planet.

Study Details

Chuanwang Yang et al, Quantifying the global eco-footprint of wearable healthcare electronics, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09819-w