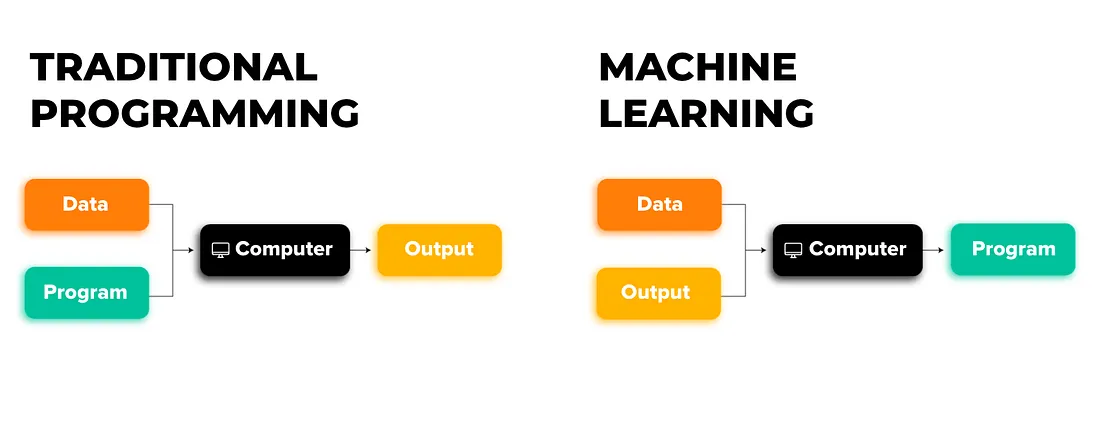

In the past, the inventions that changed the world were tangible: steam engines, light bulbs, printing presses. They could be touched, dismantled, and inspected. The rules to govern them were built on physical realities. But now, in the 21st century, humanity is grappling with something far more elusive—artificial intelligence.

AI is not just a tool; it is an ever-learning, ever-adapting force. It can write essays, diagnose diseases, negotiate contracts, and create art. It can filter job applications or decide who gets a loan. It can also be misused—to spread misinformation, design autonomous weapons, or manipulate democratic processes.

With its capabilities expanding faster than most people can comprehend, the question is no longer whether AI should be regulated—it’s how it should be regulated, and by whom. Around the world, nations are wrestling with that challenge, crafting frameworks that reflect not only their political philosophies but also their fears, hopes, and priorities.

The European Union: The Ambitious Architect of AI Rules

If one region can be called the global leader in AI regulation, it is the European Union. Building on its history of strict data protection rules under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the EU has drafted what may become the world’s first comprehensive AI law: the EU Artificial Intelligence Act.

The Act is based on a risk-tier system. Not all AI is treated equally—an AI that recommends music playlists is far less risky than an AI that decides medical treatments or controls an autonomous vehicle. The EU’s approach classifies AI applications into categories ranging from minimal risk to “unacceptable risk,” with the latter being outright banned.

For example, real-time biometric surveillance in public spaces is heavily restricted, as are AI systems that manipulate human behavior in ways likely to cause harm. On the other hand, lower-risk AI—like chatbots—faces lighter obligations, mainly transparency requirements.

What makes the EU model remarkable is its extraterritorial reach. Much like the GDPR, the AI Act will apply to any company, anywhere in the world, that offers AI products or services in the EU. This means a Silicon Valley start-up or a Shanghai tech giant must comply with Brussels’ rules if they want access to the European market.

Supporters hail the EU Act as a blueprint for ethical AI. Critics warn that overregulation could stifle innovation, pushing AI development to less regulated regions. The EU seems willing to accept that trade-off, prioritizing trust and safety over unrestrained technological growth.

The United States: The Decentralized Experiment

Across the Atlantic, the United States has taken a very different approach. There is no single, comprehensive federal AI law. Instead, the U.S. has a patchwork of guidelines, executive orders, and sector-specific rules.

Federal agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have issued warnings that deceptive or discriminatory AI practices could violate existing laws. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has developed the AI Risk Management Framework, a voluntary guide for organizations to identify and mitigate AI risks.

On the political front, the White House has released the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights, outlining principles such as data privacy, protection against algorithmic discrimination, and the right to explanation. Yet these principles are not binding—they serve more as moral guidance than enforceable law.

At the state level, California has led the charge with privacy laws that indirectly shape AI behavior, while cities like New York have passed rules requiring audits for AI systems used in hiring. The result is a regulatory landscape where compliance can vary drastically depending on geography and industry.

The American model reflects the nation’s deep-rooted skepticism toward centralized regulation and its preference for innovation-first policies. The downside is that without a unified framework, harmful AI applications can slip through the cracks until after damage has been done.

China: The Strategic Gatekeeper

China’s AI regulation is as much about governance as it is about technology. The country sees AI as both a critical driver of economic growth and a strategic tool for state power. As a result, its regulatory framework serves dual purposes: guiding development and maintaining political control.

The Interim Measures for the Management of Generative AI Services, issued in 2023, require AI providers to register with the government, ensure that their content aligns with socialist values, and prevent the generation of false or harmful information. Algorithms that recommend news or content must undergo review to avoid spreading politically sensitive material.

China has also enacted specific rules on deep synthesis technologies, which cover deepfakes and other AI-generated media. These rules mandate clear labeling of synthetic content to prevent deception.

While these measures are presented as safeguards for the public, they also reinforce the state’s control over information flow. Critics see them as a tool for censorship, while supporters argue they protect citizens from misinformation and fraud. Either way, they reflect a highly centralized approach that blends technological governance with ideological oversight.

The United Kingdom: Agile but Ambiguous

The UK, no longer bound by EU law after Brexit, has opted for a “pro-innovation” regulatory stance. Instead of a single AI law, the UK government has assigned oversight to existing regulators in specific sectors—such as healthcare, finance, and transportation—allowing them to apply AI principles in context.

This “light-touch” approach aims to encourage experimentation and attract AI businesses. The government has issued AI regulation principles—safety, transparency, fairness, accountability, and contestability—but enforcement is left to the relevant regulators rather than a central authority.

Critics argue that without binding rules, the UK risks falling behind in consumer protections. Proponents counter that flexibility will allow the UK to adapt quickly as AI technology evolves. The real test will be whether this approach can maintain public trust while keeping innovation thriving.

Canada: Balancing Innovation and Rights

Canada’s proposed Artificial Intelligence and Data Act (AIDA) seeks to create a framework that promotes responsible AI development while protecting citizens from harm. It focuses heavily on high-impact AI systems—those that could significantly affect health, safety, or fundamental rights.

AIDA requires organizations to assess and mitigate risks before deploying such systems and gives regulators the power to order changes or halt deployment if necessary. Canada’s framework also emphasizes international cooperation, recognizing that AI governance cannot be solved by one nation alone.

Canada’s approach reflects its broader political culture—a blend of progressive rights protections and openness to technological advancement. It aims for a middle path between the EU’s strict risk-based model and the U.S.’s looser innovation-first stance.

Other Notable Approaches: A Patchwork Planet

Around the globe, other nations are adding their own voices to the AI regulation conversation. Japan emphasizes voluntary guidelines and industry collaboration, reflecting its consensus-driven policy style. Australia has begun consultations on mandatory AI standards. Brazil is drafting legislation inspired by the EU model, while Singapore has issued a Model AI Governance Framework to guide companies without imposing binding rules.

This diversity of approaches means that AI companies operating internationally must navigate a complex web of obligations. An AI product that is legal in one country may be restricted—or banned outright—in another.

The Global Challenge of Harmonization

One of the thorniest issues in AI regulation is the lack of international harmonization. AI systems do not respect national borders; a chatbot hosted in one country can be accessed anywhere. This creates tension when regulations conflict.

For example, the EU’s ban on certain biometric surveillance technologies might clash with countries that permit—or even mandate—them. Similarly, requirements for transparency in AI decision-making may be difficult to reconcile with jurisdictions that protect trade secrets more aggressively.

There are ongoing efforts to address this at the international level. The OECD has issued AI principles adopted by dozens of countries, and the United Nations is exploring frameworks for AI governance. But without binding global agreements, the risk of “regulatory arbitrage” remains—where companies base operations in the least restrictive jurisdictions to avoid compliance costs.

Why Emotion Matters in AI Regulation

At its core, AI regulation is not just a technical or legal matter—it is deeply human. Behind every algorithm are human choices about what data to use, what outcomes to optimize, and what trade-offs to accept. These choices can amplify biases, determine economic futures, and shape the cultural narratives that societies live by.

Public trust is the invisible currency of AI. Without it, even the most powerful AI systems will face resistance. Regulations are one way of building that trust, signaling to citizens that their rights and safety are being taken seriously. But the way regulations are written—and enforced—will determine whether that trust grows or erodes.

The Road Ahead: An Unfinished Story

AI is still in its relative infancy. The rules we make now will be the scaffolding for a technology that could last centuries. The challenge for lawmakers is to create regulations that are strong enough to prevent harm, flexible enough to adapt to rapid change, and fair enough to win global legitimacy.

History shows that regulation often lags behind innovation—but it also shows that societies can learn from one another. The EU, the U.S., China, and others are running parallel experiments in AI governance. The outcomes of these experiments will inform not just policy, but the kind of future we inhabit.

As AI continues to learn from us, perhaps we must also learn from each other—across borders, industries, and ideologies. The goal is not just to control the machine, but to ensure that the machine serves humanity’s highest values.