It starts innocently enough. A low-calorie diet, a commitment to “eat clean,” maybe after a holiday binge or in anticipation of summer. The pounds shed feel like a triumph—but they creep back, bringing along more than before. You try again. Restrict, lose, regain. And with each cycle, something changes—not just in your weight, but in the way you eat, in the way you feel around food.

For millions, this familiar pattern is more than just frustrating—it’s emotionally and physiologically destabilizing. Now, for the first time, scientists have discovered that the root of this vicious cycle may not lie solely in willpower, psychology, or metabolism. The answer, it turns out, may live deep within your gut.

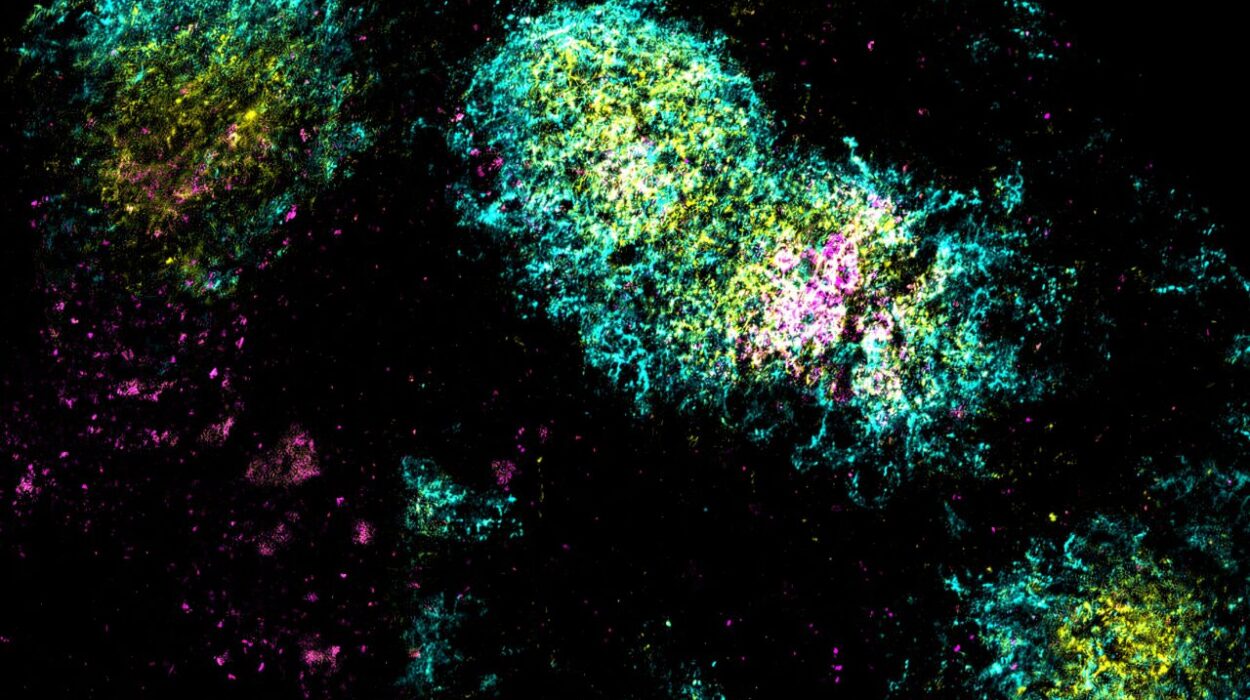

In a study that could reshape how we understand eating disorders and obesity, researchers from INRAE, CNRS, the University of Rennes, and Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté have found that gut microbiota—those trillions of microscopic organisms that dwell in our digestive tract—play a direct role in the development of binge eating behavior linked to repeated dieting. And astonishingly, this behavior can be transmitted from one individual to another through gut bacteria alone.

The results, published in the journal Advanced Science, unveil a hidden biological legacy of yo-yo dieting—and offer a stark warning about how the gut can silently rewire the brain’s relationship with food.

The Gut-Brain Conversation We Didn’t Know We Were Having

The idea that gut bacteria influence our health is no longer new. From immunity and mood to inflammation and even cognition, the microbiota has emerged as a powerful player in our biology. But until now, its role in disordered eating behaviors—especially those triggered by cycles of restrictive dieting—has been largely unexplored.

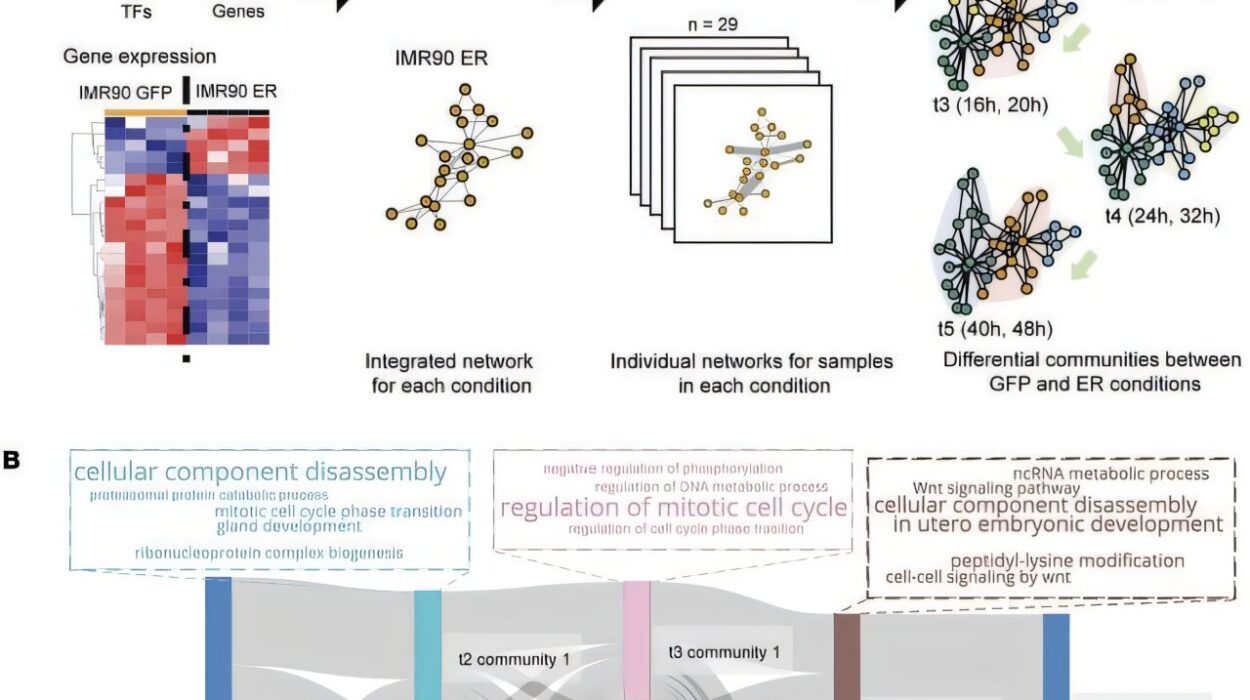

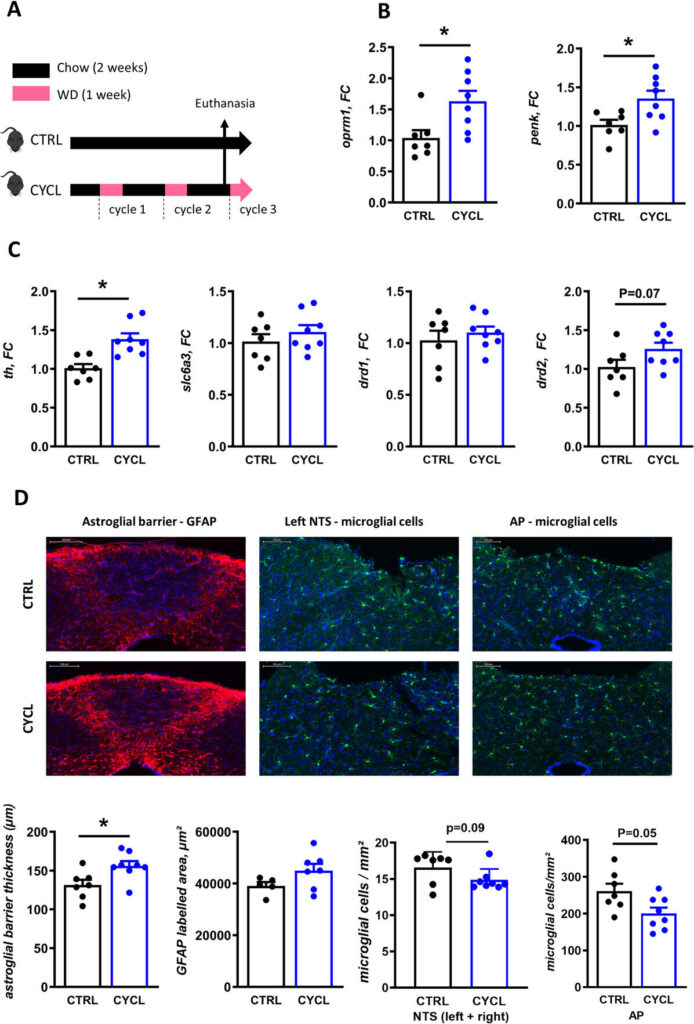

To investigate, the French research team designed a preclinical study using mice as a model. The animals were put on a fluctuating diet that mimicked human yo-yo dieting: a normal, balanced diet alternated with high-fat, high-sugar meals. Over time, the mice began to exhibit clear signs of binge eating. They would compulsively overconsume the fatty, sugary foods even after periods of restriction had ended.

But the most revealing part of the experiment came next.

Passing on the Craving

The team collected fecal samples from the binge-eating mice and transplanted their gut microbiota into healthy mice that had never been exposed to the yo-yo diet. What happened next was remarkable.

The recipient mice, despite never having undergone dietary restriction or exposure to junk food cycles, began to display the same binge-like behavior. They too sought out and overate the high-fat, high-sugar foods, mimicking the behavior of their microbiota donors.

In essence, the disordered eating pattern had been biologically transmitted—not through environment or upbringing, but through microbes.

“We were stunned,” said one of the study’s lead scientists. “This was a clear demonstration that gut microbiota alone were sufficient to trigger compulsive eating behaviors.”

Rewiring the Brain from the Gut Up

Digging deeper, the researchers looked at how this microbial influence was affecting the brain. What they found was equally startling.

In the mice with altered microbiota, key genes involved in the brain’s reward system—particularly those that influence how we feel pleasure and craving in response to food—were more active. The brainstem, a critical gateway where signals from the gut are processed, also showed cellular changes.

In other words, the gut microbes weren’t just nudging eating habits. They were reshaping the brain’s wiring, making it more prone to seek out rewarding, high-calorie food—and less able to regulate that drive.

This finding aligns with previous theories that the gut and brain form a two-way communication superhighway, often referred to as the gut-brain axis. But the study takes it further, showing that our gut flora can essentially “train” the brain to want more of the very foods that dieting tries to restrict.

The Unintended Consequences of Diet Culture

The implications of this discovery are profound. According to estimates, over 42% of adults in Western countries have attempted some form of calorie-restricted dieting. Many do so repeatedly, entering the cycle of weight loss and regain that characterizes yo-yo dieting.

What this new research shows is that these cycles may not only fail in the long term—they may actually make things worse, by biologically increasing a person’s risk of developing disordered eating behaviors such as binge eating.

And because the microbiota is so deeply intertwined with metabolic and psychological health, the fallout may extend beyond food itself—into areas like anxiety, self-image, and even mood disorders.

Why the Microbiome Matters in Treating Disordered Eating

While this study was conducted in mice, the mechanisms involved are highly relevant to humans, whose microbiota are even more complex and sensitive to dietary patterns.

For medical professionals and psychologists working in the field of obesity and eating disorders, the message is clear: it’s time to start taking the gut microbiome seriously as a factor in patient care. Diets that ignore its role may be setting patients up for deeper struggles.

“The gut is not just a digestive organ—it’s a central player in emotional and behavioral health,” said one of the study authors. “If we overlook that, we may miss key drivers of disordered eating.”

The team now plans to follow up with human studies—looking at individuals who have experienced yo-yo dieting and analyzing their microbiota to see if similar patterns emerge. Surveys, stool samples, and behavioral analyses will help determine how these findings might translate into clinical settings.

Hope for a New Approach to Weight and Wellness

Despite the troubling implications, this research also offers a glimmer of hope. If gut microbiota can drive disordered eating behaviors, they may also hold the key to preventing or reversing them.

By identifying specific bacterial signatures linked to binge eating, scientists may one day be able to develop personalized microbiota-based therapies. These could include targeted probiotics, dietary interventions, or even microbiome transplants aimed at restoring a healthier balance and breaking the cycle.

In the meantime, the study calls for a gentler, more holistic view of dieting and body weight—one that moves away from extreme restrictions and recognizes the delicate ecosystem inside us.

After all, what we eat doesn’t just change our weight. It changes who we are—from the gut, to the brain, to the choices we don’t even realize we’re making.

The Takeaway

What started as an investigation into the biology of weight loss has opened a new chapter in our understanding of the human body. The gut, once seen as a passive recipient of food, is now recognized as a powerful agent of behavior and emotion.

The next time someone blames a binge on a lack of willpower, they may be pointing in the wrong direction. The truth, as this study shows, may be buried much deeper—hidden in a microscopic world we’re only beginning to understand.

Reference: Mélanie Fouesnard et al, Weight Cycling Deregulates Eating Behavior in Mice via the Induction of Durable Gut Dysbiosis, Advanced Science (2025). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202501214