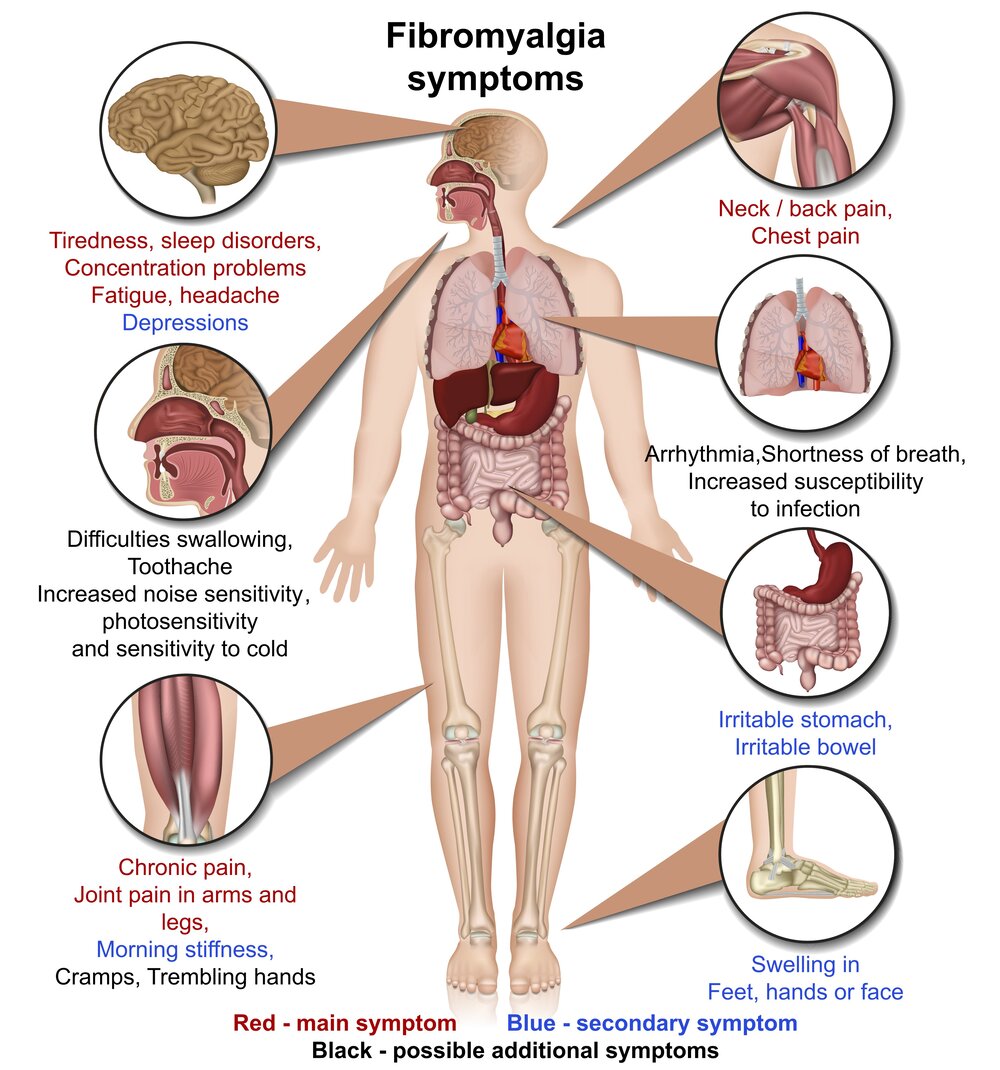

Fibromyalgia occupies a strange place in the medical world. It’s a condition that causes widespread pain, extreme fatigue, and a constellation of other symptoms, yet presents no visible signs of damage or disease in the muscles, joints, or organs. For years, many dismissed it as psychological or “not real,” but science is slowly peeling back the layers of this elusive illness. Today, fibromyalgia is recognized as a legitimate neurological condition rooted in real, measurable changes in how the brain and nervous system process pain.

Understanding fibromyalgia is like trying to map a ghost—it leaves no scars, no inflammation, and no structural abnormalities. But make no mistake: the pain is real. For the millions affected—mostly women but also men and children—the suffering is as palpable as any broken bone or inflamed joint. The challenge lies in understanding how a body can hurt so profoundly without any apparent injury.

The Long Road to Recognition

Fibromyalgia is not new, though its name is. In the 19th century, doctors referred to similar symptoms as “muscular rheumatism.” Patients would report deep, aching pain, profound exhaustion, and poor sleep, often with no apparent cause. As medicine became more sophisticated, these cases remained medical puzzles. There was no inflammation, no infection, and no consistent laboratory abnormality. As a result, many physicians chalked it up to hysteria, depression, or malingering.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that the condition began to gain recognition. In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology proposed the first diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia, requiring patients to have widespread pain and tenderness in at least 11 of 18 specified “tender points.” Though this method has since evolved, it was a pivotal moment—it said to patients, “Your pain is real, and it has a name.”

Fibromyalgia’s journey into mainstream medicine has been one of slow but steady validation. Along the way, it has challenged how medicine defines disease, how it measures pain, and how it treats chronic conditions that don’t fit neatly into biological models.

The Central Nervous System as the Epicenter of Pain

The hallmark of fibromyalgia is pain—but not the kind of pain that results from injury or inflammation. Instead, fibromyalgia involves pain processing gone awry. Research increasingly points to the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) as the core of the problem.

People with fibromyalgia appear to have a lowered threshold for pain. Sensations that might be mildly uncomfortable to others are perceived as intensely painful. This phenomenon is called “central sensitization.” It’s as if the body’s volume knob for pain has been turned up and left there.

In a healthy system, pain signals travel from the body to the spinal cord and then up to the brain, where they are interpreted and responded to. In fibromyalgia, the system becomes hyperactive. The brain overreacts to incoming signals and may even generate pain independently of any external stimulus. Brain imaging studies have shown increased activity in pain-related regions in fibromyalgia patients even when no painful stimulus is applied. It’s not just that patients feel more pain—it’s that their brains are wired to detect and amplify it.

Neurochemistry of a Disordered Pain System

The overactive pain processing seen in fibromyalgia is likely rooted in chemical imbalances within the brain. Several neurotransmitters—chemical messengers that help nerves communicate—are altered in fibromyalgia.

One of the main culprits is substance P, a molecule involved in transmitting pain signals. Studies show that fibromyalgia patients have up to three times the normal levels of substance P in their spinal fluid. This increase may explain why their nerves are so quick to shout “pain!”

Meanwhile, levels of serotonin and norepinephrine—two neurotransmitters involved in inhibiting pain—are often low. These same chemicals also regulate mood and sleep, perhaps explaining why depression, anxiety, and insomnia are so tightly intertwined with fibromyalgia. Low levels of dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved in motivation and reward, may also contribute to the mental fog and lack of motivation often reported by patients.

This cocktail of neurochemical imbalance paints a picture of a nervous system that’s both overly excitable and poorly equipped to dampen down its own alarms. It’s a recipe for constant pain, poor sleep, and emotional exhaustion.

Sleep That Fails to Refresh the Body and Mind

One of the most disruptive aspects of fibromyalgia is not just the pain itself, but the fatigue that accompanies it. This is not ordinary tiredness. It’s a bone-deep, mind-numbing exhaustion that lingers no matter how much rest a person gets. And often, the rest they do get is poor.

Polysomnographic studies—sleep studies that monitor brain activity—reveal that people with fibromyalgia often fail to enter the deep stages of sleep. Known as “non-restorative sleep,” this phenomenon means that the body and brain never fully recover during the night. Instead of waking refreshed, patients wake feeling as though they’ve been hit by a truck.

Sleep disturbances further disrupt pain regulation. Deep sleep is when the body repairs tissues and modulates pain sensitivity. Without it, the nervous system becomes even more sensitized, creating a vicious cycle: pain disrupts sleep, and poor sleep amplifies pain.

This exhaustion spills into every corner of life. It becomes harder to concentrate, harder to remember things, harder to stay motivated. Many patients describe a sensation known as “fibro fog”—a cognitive haze that makes even simple tasks feel overwhelming. In this way, fibromyalgia doesn’t just tax the muscles—it burdens the very act of being.

The Genetics and Biology Behind Vulnerability

While fibromyalgia is not strictly genetic, family history does play a role. Studies show that people with a first-degree relative who has fibromyalgia are several times more likely to develop it themselves. This suggests a genetic predisposition, though no single “fibromyalgia gene” has been found.

Instead, the genetic contribution seems to involve subtle variations in multiple genes—especially those related to neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. These genetic quirks may render some people more sensitive to pain, more vulnerable to stress, or less able to recover from trauma.

But genetics are only part of the equation. Environmental factors such as infections, injuries, psychological trauma, or chronic stress often act as triggers. Many patients report that their symptoms began after a specific event—a car accident, a viral illness, or a period of intense emotional stress. It’s as though these experiences flipped a switch in the nervous system, one that could not be turned off again.

This interplay of biology and experience places fibromyalgia within a broader class of conditions known as central sensitivity syndromes. These include irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, and temporomandibular joint disorder. In all of them, the nervous system becomes hyper-responsive, and normal sensations are amplified into pain or discomfort.

The Role of Inflammation Without the Classic Markers

Unlike autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, fibromyalgia does not show signs of classic inflammation. There are no swollen joints, no elevated white blood cell counts, and no damaged organs. Yet some researchers suspect that a more subtle form of inflammation—perhaps at the level of the nervous system—may be at work.

Recent studies have begun to explore the role of neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia. In particular, glial cells—support cells in the brain and spinal cord—may play a role. When activated, these cells release inflammatory chemicals that can irritate neurons and amplify pain signals. In fibromyalgia, glial activation may contribute to the central sensitization that defines the condition.

This discovery is still in its early stages, but it opens new doors. If inflammation in the nervous system is part of the problem, then anti-inflammatory therapies targeted at glial cells could represent a new frontier in treatment.

Diagnostic Challenges in a World That Favors the Visible

One of the most frustrating aspects of fibromyalgia is how difficult it is to diagnose. There’s no blood test, no imaging scan, no biopsy that can definitively confirm it. Doctors must rely on a patient’s history, symptoms, and the exclusion of other conditions.

This diagnostic ambiguity has contributed to skepticism and stigma. Many patients spend years being misdiagnosed or dismissed. They are told they’re just stressed, anxious, or exaggerating. Some are prescribed antidepressants not for the mood symptoms, but as a way to send them on their way.

But this is changing. New diagnostic criteria introduced in 2010 and revised in 2016 have shifted away from the old “tender point” exam and toward a broader assessment of symptoms. These include widespread pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and cognitive problems. The new criteria are more inclusive and more accurate, capturing the true breadth of the condition.

Still, the absence of a definitive test remains a barrier. In a medical system that prizes objectivity, fibromyalgia asks clinicians to trust what they cannot see—something that many still struggle to do.

Treatment as a Journey, Not a Cure

There is no cure for fibromyalgia, but there is hope. Treatment focuses on managing symptoms and improving quality of life. This often requires a combination of strategies—pharmacological, psychological, and lifestyle-based.

Medications can help, particularly those that modulate neurotransmitters. Drugs like duloxetine and milnacipran increase levels of serotonin and norepinephrine, reducing pain perception. Gabapentinoids such as pregabalin can dampen nerve excitability. However, medications alone are rarely enough.

Exercise is perhaps the most powerful intervention. Though counterintuitive—why move when movement hurts?—regular, gentle aerobic activity can reduce pain and fatigue over time. It reconditions the body, boosts endorphins, and helps recalibrate the nervous system.

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) offer psychological tools to cope with chronic pain. They don’t deny the reality of symptoms; rather, they teach patients how to live better within the boundaries the illness imposes.

Sleep hygiene, nutritional support, massage, acupuncture, and other integrative therapies can also play a role. For many, managing fibromyalgia becomes a lifestyle—a set of habits and strategies designed to keep the pain dialed down and the energy dialed up.

Rethinking Pain and the Mind-Body Divide

Fibromyalgia challenges many of our cultural assumptions about pain. It forces us to reconsider the artificial division between mind and body, between physical and psychological suffering. It reminds us that pain is not simply a signal of injury—it is an experience shaped by memory, emotion, expectation, and context.

The nervous system is not a passive conduit for signals from the body. It is an active interpreter, a sculptor of experience. In fibromyalgia, that sculptor becomes overzealous, carving pain where none is needed.

Understanding this does not mean dismissing the pain as imaginary. On the contrary, it demands a deeper appreciation of how real pain can arise from invisible processes. It invites a more compassionate and sophisticated approach to chronic illness—one that honors both the biology and the lived experience of the patient.

The Path Forward in Research and Awareness

Science is catching up. Advances in neuroimaging, genetics, and molecular biology are beginning to unravel the mysteries of fibromyalgia. Researchers are exploring biomarkers, investigating neuroimmune interactions, and developing more targeted therapies. Awareness among physicians is improving, though gaps remain.

But perhaps the most important progress is in how society views invisible illness. As fibromyalgia becomes better understood, it also becomes more visible—not on scans, but in the public consciousness. Patients are no longer dismissed as weak or neurotic. They are seen as survivors of a complex neurological storm.

The path forward is not easy, but it is brighter than ever. Each study, each patient voice, each moment of validation brings us closer to a world where fibromyalgia is no longer a mystery but a solvable piece of the human puzzle.