Imagine being jolted awake by an intense, burning pain in your big toe. The joint is red, hot, and swollen. Even the touch of a bedsheet feels unbearable. You haven’t injured yourself, and you didn’t see this coming—but the pain is relentless. This isn’t just any inflammation. This is gout, one of the most ancient and misunderstood diseases in human history.

Gout has tormented kings, commoners, and intellectuals for centuries. Historically labeled the “disease of kings” because of its association with rich foods and luxury, gout has earned a dramatic reputation. But behind the myths and old-world medical ideas lies a surprisingly modern and well-understood condition rooted in chemistry, metabolism, genetics, and lifestyle.

To truly grasp what causes gout—and how to manage it—you have to step into the microscopic world of crystals, uric acid, and a delicately balanced biochemical system that sometimes tips into chaos.

Understanding the Chemistry of Uric Acid

At the heart of gout lies a molecule known as uric acid. It’s a waste product, a result of the body breaking down substances called purines. Purines are found naturally in the body’s cells and in many foods we eat, especially meats, seafood, and alcohol. When purines are metabolized, they’re converted into uric acid, which then travels through the bloodstream to the kidneys, where it’s normally excreted in urine.

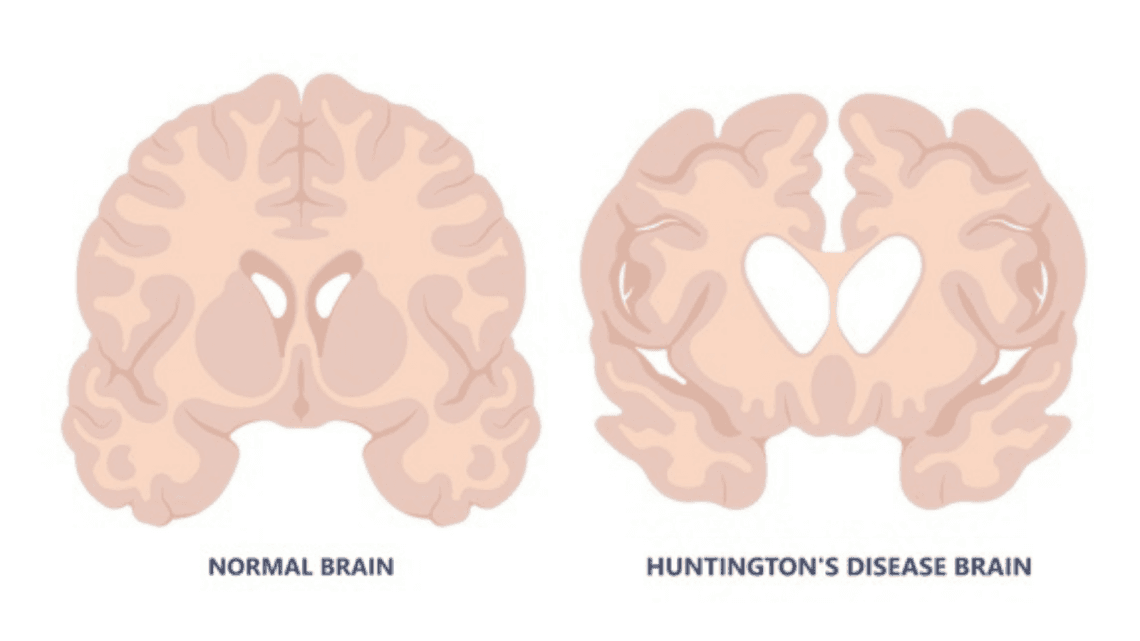

But problems begin when the body either produces too much uric acid or can’t get rid of enough of it. When uric acid levels in the blood rise too high, a condition known as hyperuricemia, the excess begins to crystallize—especially in cooler parts of the body like the joints of the toes. These needle-shaped crystals lodge themselves into joint tissue, triggering the body’s immune system to respond as though there were a foreign invader.

The result is a painful flare-up: inflammation, swelling, heat, and redness. This is not a subtle ache; it’s often described as one of the most excruciating forms of arthritis.

Why the Big Toe Often Takes the First Hit

One of the peculiar features of gout is its tendency to target the joint at the base of the big toe—a condition medically known as podagra. But gout doesn’t stop there. Over time, it can affect the ankles, knees, wrists, fingers, and elbows. So why does it so often begin in the toe?

There are a few theories. The big toe joint is relatively distant from the heart, meaning blood flow there is slower and the temperature slightly lower. This cooler environment makes it easier for uric acid to form crystals. It’s also a joint that bears a lot of mechanical stress from walking and standing, making it a prime location for damage or irritation—both of which can exacerbate crystal formation.

Furthermore, when a person lies down to sleep, fluids in the body redistribute, and uric acid may accumulate in lower extremities. Add dehydration or a late-night feast, and you’ve got the perfect storm for a midnight attack.

The Role of Diet and Lifestyle in Triggering Gout

Though gout has a genetic component, lifestyle factors play a major role in whether or not the condition actually manifests. Rich, purine-heavy foods such as red meat, organ meats, shellfish, and certain fish like anchovies and sardines are notorious for raising uric acid levels. But the real dietary villain might surprise you—fructose.

Fructose, a sugar found in fruit but especially abundant in sweetened beverages like sodas and fruit juices, ramps up uric acid production in the liver. When consumed in excess, it overwhelms the body’s ability to process it, leading to a spike in uric acid levels.

Alcohol, particularly beer and spirits, is another major contributor. Alcohol increases purine breakdown and simultaneously impairs kidney function, reducing the excretion of uric acid. Beer is doubly problematic because it contains both alcohol and purines from brewer’s yeast.

Being overweight or obese compounds the risk. Fat cells produce more uric acid, and extra weight stresses the kidneys, reducing their ability to eliminate it. Additionally, metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions including high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and high triglycerides—is closely linked to elevated uric acid levels and increased gout risk.

The Genetic Link That Sets the Stage

Even with a perfect lifestyle, some people are genetically predisposed to gout. Studies have identified several genes that affect how the body handles uric acid—specifically, how well the kidneys can excrete it. One gene in particular, SLC2A9, plays a role in uric acid transport and regulation. Variations in this gene can make it harder for the kidneys to filter uric acid out of the bloodstream.

Gout often runs in families. If your parents or siblings have it, your risk is significantly higher. But having the gene doesn’t guarantee an attack. Rather, it sets the stage. Diet, stress, and other triggers act as the cues that determine whether or not a gout flare will strike.

This interplay between nature and nurture explains why some people can eat steak and drink beer without consequence, while others are beset by agonizing pain after a seemingly minor indulgence.

When the Immune System Turns Against Crystals

Once uric acid crystals settle into the joint, the immune system swings into action. Specialized white blood cells called neutrophils rush in, attempting to engulf and destroy the crystals. But this response can backfire.

The immune cells release inflammatory chemicals, and the affected joint becomes a battleground. The inflammation causes severe swelling, redness, and intense pain. This acute phase can last for several days to a week before subsiding.

With repeated attacks, the situation can worsen. Over time, chronic gout can lead to the formation of tophi—lumps of uric acid crystals that collect under the skin or around joints. These tophi are visible, often disfiguring, and can cause permanent joint damage. Chronic inflammation may also erode cartilage and bone, leading to long-term disability if not properly managed.

Gout as a Red Flag for Other Health Conditions

Gout doesn’t always occur in isolation. It often coexists with a host of other health problems. High uric acid levels are frequently found in people with kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. In fact, gout is now considered a marker of broader metabolic dysfunction.

One reason for this connection lies in shared risk factors: poor diet, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle. But there’s growing evidence that uric acid itself may play a direct role in promoting inflammation, insulin resistance, and vascular damage.

This makes gout more than just a painful nuisance. It’s a signal—a warning light flashing on the dashboard of the body’s metabolic engine. Ignoring it means missing an opportunity to prevent more serious conditions down the road.

How to Diagnose Gout and Rule Out Impostors

Because its symptoms can resemble other forms of arthritis or infections, gout diagnosis often requires a combination of clinical judgment and laboratory analysis. A definitive diagnosis is made when urate crystals are found in joint fluid, extracted through a needle during a gout flare.

Blood tests can reveal high uric acid levels, but this alone isn’t always conclusive. Some people with high uric acid never develop gout, while others suffer attacks even when their uric acid levels are normal at the time of testing.

Imaging techniques like ultrasound or dual-energy CT scans can detect urate deposits in joints and tissues. These tools are especially useful in chronic cases where the diagnosis might be less clear.

Because of its episodic nature, gout is sometimes misdiagnosed or dismissed, especially during symptom-free periods. A correct and timely diagnosis is critical—not just to relieve pain but to prevent irreversible joint damage and long-term complications.

The Battle Plan for Managing Gout

Gout is highly treatable, and with the right strategy, most people can live free of painful flares. Treatment generally involves two fronts: acute attack management and long-term prevention.

When a gout attack strikes, the immediate goal is to reduce inflammation and relieve pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like indomethacin are commonly prescribed. Corticosteroids or colchicine—a plant-derived compound that interferes with inflammatory pathways—are also used to dampen the immune response.

But short-term relief isn’t enough. The underlying problem—elevated uric acid—must be addressed to prevent future attacks. That’s where urate-lowering therapy comes in.

Medications like allopurinol and febuxostat reduce uric acid production by inhibiting xanthine oxidase, the enzyme responsible for converting purines to uric acid. Others, like probenecid, enhance the kidney’s ability to excrete uric acid. These treatments are often lifelong and require careful dose adjustment and monitoring.

During the initiation of urate-lowering therapy, gout flares may paradoxically increase as crystals dissolve and trigger inflammation. That’s why doctors often prescribe anti-inflammatories alongside these medications during the early phase of treatment.

The Dietary and Lifestyle Overhaul That Makes a Difference

While medication is essential for many, lifestyle changes amplify its effects and, in some cases, may even allow for drug-free management. Reducing intake of high-purine foods—especially red meat, shellfish, and organ meats—can lower uric acid levels. Replacing beer with water or low-fat dairy, which appears to reduce uric acid, can help too.

Limiting sugary drinks and cutting back on fructose-rich foods is critical. Obesity and insulin resistance are major risk factors, so weight loss through a balanced diet and regular exercise significantly improves outcomes.

Staying hydrated is another key strategy. Water dilutes uric acid and supports kidney function. Aim for at least 8–10 cups per day, more if you’re active or live in a hot climate.

And don’t forget stress management. High stress levels can trigger flares, perhaps by promoting inflammatory hormones. Practices like meditation, yoga, or even regular walks can support both mental and physical health.

Living with Gout Without Letting It Define You

Though gout is chronic, it doesn’t have to be a life sentence of suffering. With awareness, modern treatment, and proactive self-care, many people live long, healthy, pain-free lives. The key is to recognize the condition early and to treat it not just as a joint disease but as part of a broader metabolic picture.

What’s more, there’s a growing movement to destigmatize gout. For too long, it has been trivialized as a disease of indulgence or poor lifestyle choices. In truth, it’s a complex interaction between genes, environment, and biochemistry.

People with gout are not weak-willed or gluttonous. They are navigating a delicate metabolic dance, one that requires compassion, scientific understanding, and long-term commitment.

The Future of Gout Research and Hope for a Cure

Science is steadily advancing. New drugs are being developed to more effectively lower uric acid and reduce inflammation. Researchers are exploring the gut microbiome’s role in uric acid metabolism and investigating genetic therapies to correct underlying transport dysfunctions.

One particularly exciting area involves biologic treatments that neutralize the body’s inflammatory response to crystals. Others focus on targeting enzymes involved in uric acid production more precisely, with fewer side effects.

As we continue to decode the molecular and genetic mechanisms behind gout, the dream of a lasting cure moves closer. In the meantime, our understanding of how to live well with the disease is better than it’s ever been.

If you’d like this article in PDF form, a condensed version, or additional visual aids like diagrams or timelines, feel free to request them!