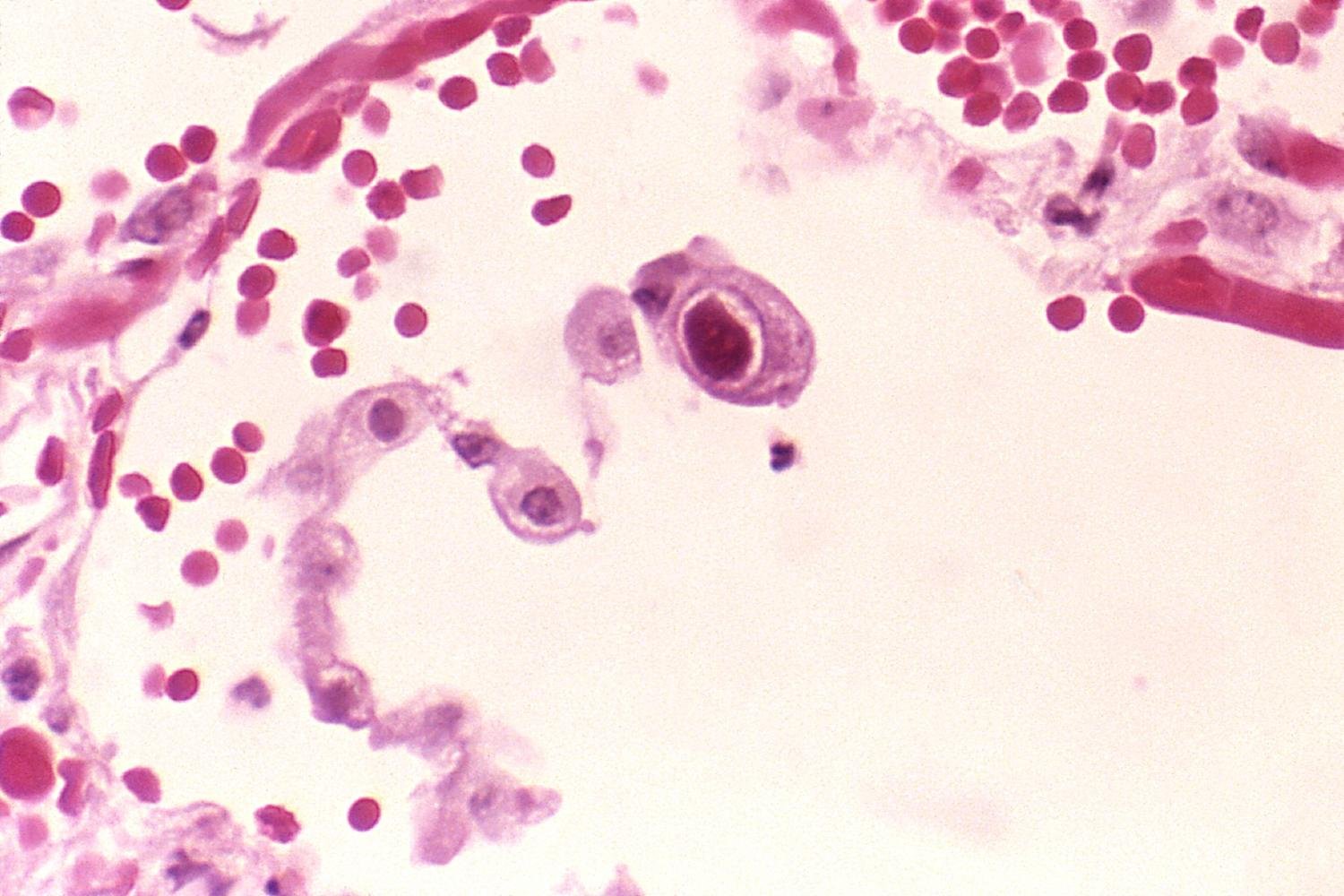

In the invisible war raging inside the human body, some enemies hide in plain sight. Among the most elusive is cytomegalovirus—better known as CMV—a virus that infects most adults around the world without a whisper of a symptom. Yet for pregnant women and people with weakened immune systems, this quiet invader can wreak heartbreaking consequences: birth defects, lifelong disabilities, and sometimes, death.

Now, scientists have uncovered a vital secret of CMV’s stealth tactics—a revelation that could transform the fight against one of the leading infectious causes of birth defects in the United States. The discovery, published in Nature Microbiology by researchers from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, shines a light on a previously unknown entryway CMV uses to invade the body’s cells and avoid detection.

And that secret “door”—called GATE—might just become the key to finally stopping the virus.

An Old Foe with New Tricks

CMV belongs to the herpesvirus family, alongside Epstein-Barr virus, chickenpox, and herpes simplex. Like its viral cousins, CMV is a master of disguise. For healthy adults, it typically causes no symptoms at all. But when the immune system is compromised—or during pregnancy—the virus reveals its darker side.

In the United States, about 1 in 200 babies is born with congenital CMV. Of those, roughly one in five will suffer serious consequences: hearing loss, vision impairment, seizures, and long-term developmental delays. CMV is also a major risk for people undergoing organ transplants or living with immunosuppressive conditions.

Despite decades of research, scientists have struggled to develop a vaccine or antiviral therapy that can effectively block CMV. Part of the reason lies in the virus’s genetic complexity—it has one of the largest genomes among known viruses. But as it turns out, it was also hiding a molecular weapon that no one had seen before.

The Discovery: A Hidden Entry Point

“We found a missing puzzle piece,” said senior author Dr. Jeremy Kamil, associate professor of microbiology and molecular genetics at the University of Pittsburgh. “And it may explain why CMV has been so hard to stop.”

Like other herpesviruses, CMV relies on a protein called gH to enter cells. Most herpesviruses pair gH with another protein called gL to breach a cell’s outer defenses. But CMV is different. Instead of following the typical path, the virus swaps out gL for a new partner: UL116, and adds a third accomplice, UL141.

Together, these three proteins form what the scientists call GATE—a complex that allows CMV to enter the cells that line blood vessels. More importantly, GATE provides a side entrance that bypasses the immune system’s normal alarm bells.

It’s a strategy as cunning as it is effective. The virus not only gains access to vulnerable cells—it also cloaks itself from detection.

“This is a mechanism we didn’t realize existed,” said Dr. Chris Benedict, co-senior author and associate professor at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology. “It’s like the virus built its own secret passage—and until now, we didn’t know where to look.”

Why This Changes Everything

The discovery of the GATE complex offers a possible explanation for why vaccine development efforts have repeatedly failed. Most attempts have focused on the standard viral machinery seen in other herpesviruses, not realizing that CMV was playing by its own rules.

Now, by targeting the GATE complex directly, scientists have a new strategy: block the side door, and you may stop the infection altogether.

“Previous vaccine strategies may have been aiming at the wrong targets,” said Benedict. “But with this new understanding, we can develop more effective approaches—potentially vaccines or antiviral drugs that disrupt CMV’s entry pathway.”

And because GATE may not be unique to CMV, this discovery could have even broader implications. Other members of the herpes family, including Epstein-Barr virus (linked to some cancers) and varicella-zoster (the cause of chickenpox and shingles), may use similar entry strategies.

A Lifelong Infection—And a Lifelong Hope

CMV is known as a “lifelong” virus. Once it infects a person, it stays in the body for life, often lying dormant but capable of reactivating. That makes prevention even more critical—especially during pregnancy, when the virus can silently cross the placenta and damage a developing baby’s brain, ears, or eyes.

“If we can develop antiviral drugs or vaccines that inhibit CMV entry, this will allow us to combat the many diseases this virus causes in developing babies and immune-compromised people,” said Dr. Erica Ollmann Saphire, president and CEO of the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, and a co-author of the study.

The prospect of a CMV vaccine, once elusive, now feels closer.

For parents, for organ transplant patients, and for people living with suppressed immune systems, that could mean fewer nightmares and more peace of mind.

A New Chapter in Virology

Science has always been a story of searching—of peering into the unseen and asking, Why? Sometimes the answer comes not with a bang, but with a key. GATE is that key.

This discovery not only rewrites what we know about one of the world’s most common viruses—it opens the door to a future where CMV’s quiet threat can be silenced.

As Kamil put it: “If we don’t know what weapons the enemy is using, it’s hard to protect against it. Now, we know. And that changes everything.”

Reference: The GATE glycoprotein complex enhances human cytomegalovirus entry in endothelial cells, Nature Microbiology (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-025-02025-4, www.nature.com/articles/s41564-025-02025-4