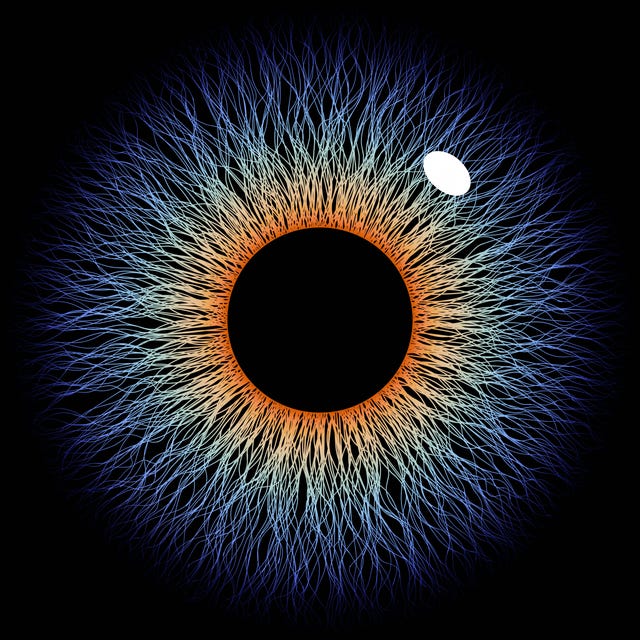

It feels impossible, almost poetic, that every human being walks through the world with a small hole in their vision and never notices it.

Inside each of our eyes lies a visual blind spot, the precise place where the optic nerve connects to the retina. In that tiny region, there are no light-detecting cells. No signals. No image. If a small object lands exactly there, it simply disappears from awareness.

And yet, our world does not flicker or fracture. We do not see gaps floating in midair. The visual scene feels whole, continuous, and solid.

For decades, scientists have wondered: does the brain truly fill in this gap perfectly, or does the blind spot subtly distort how we experience space? A newly published research protocol in PLOS One sets out to test that question in an unusually ambitious way. Rather than simply measuring perception, it aims to pit three major theories of consciousness against one another and see which one best explains how we experience space around this hidden void.

Three Competing Visions of Consciousness

At the heart of this investigation are three powerful and contrasting frameworks: Integrated Information Theory (IIT), Predictive Processing Active Inference (AI), and Predictive Processing Neurorepresentationalism (NREP).

Each offers a different explanation for how conscious experience arises. And each makes a different prediction about what should happen near the blind spot.

According to IIT, the quality of conscious experience depends on the structure of cause-and-effect relationships in the brain. From this perspective, the blind spot is not just an absence of input. It is a structural feature that should alter the underlying cause-effect organization. If that is true, then spatial perception near the blind spot should be warped or distorted in measurable ways.

The two predictive processing theories tell a different story. Both AI and NREP argue that perception relies on internal models. The brain constantly predicts incoming sensory information and updates those predictions to reduce prediction errors. In this view, the blind spot is simply another irregularity that the brain’s model learns to compensate for.

If these models work well, distortions near the blind spot should be small or even nonexistent.

But even these two predictive approaches part ways in subtle but important ways.

NREP suggests that if part of the visual field is damaged or missing, spatial judgments could be affected. However, information from the intact areas of vision would largely compensate. There might be slight distortions, but they would be corrected by the surrounding evidence.

AI, on the other hand, takes a more radical stance. It argues that conscious spatial experience depends on a generative model suited for active vision, one that follows a form of projective geometry rather than mirroring the anatomy of the eye itself. In this framework, perceptual judgments should not change simply because the blind spot exists. The only difference might be an increase in perceptual uncertainty, since sensory sampling differs in that region.

So the stage is set. One theory predicts spatial warping. Two predict little to no distortion. Now comes the test.

Three Simple Tasks With Profound Implications

To explore these predictions, researchers designed three carefully controlled psychophysical tasks. Each one targets a different aspect of spatial perception.

Participants will first complete a distance estimation task. They will look at pairs of dots and judge how far apart they appear. Sometimes the imaginary line between the dots will span the blind spot. Other times it will not. If space is subtly distorted near the blind spot, those distance judgments could shift.

Next comes the area size task. Participants will compare circles and judge their apparent size. Some circles will surround the blind spot; others will appear elsewhere. If the blind spot reshapes spatial experience, a circle near it might appear larger or smaller than it truly is.

Finally, there is the motion curvature task. Participants will observe moving paths and judge their curvature. Some motion trajectories will pass near the blind spot; others will not. Even a slight bending of perceived motion could reveal hidden distortions.

To ensure precision, the experiments use colored glasses for dichoptic presentation, meaning images can be shown to one eye at a time. This allows researchers to stimulate areas near the blind spot without interference from the other eye. Eye tracking will confirm that participants maintain accurate fixation, preventing accidental stimulation outside the intended region.

The researchers anticipate that any effects might be subtle. To detect them, they estimate needing around 32 participants per experiment. The resulting data will be analyzed using linear mixed-effects models and Bayesian model comparison, statistical approaches designed to weigh how much evidence supports each theory.

A Glimpse Into Simulated Futures

Before running the experiments with real participants, the team generated simulated data based on what each theory predicts.

The results paint three different possible futures.

Under IIT, the blind spot produces spatial warping. Distances might stretch or compress. Areas might shift in perceived size. Motion paths could subtly curve.

Under AI and NREP, distortions are minimal. Spatial judgments remain largely stable, though there could be small decreases in precision. The world might feel slightly less certain near the blind spot, but not structurally bent.

These simulations offer a roadmap. If real-world data resemble the warping pattern, IIT gains support. If perception remains stable, the predictive theories gain ground.

Yet science rarely unfolds cleanly.

When Theories Meet Reality

The researchers acknowledge that interpreting real data may prove challenging.

The theories predict the direction of possible effects, but not necessarily their magnitude. A distortion might exist, but how large would it need to be to favor one theory over another? That line may not be sharp.

Even more intriguing is the possibility of unexpected findings. Imagine if an object appears larger when a theory predicts it should appear smaller. Such a result might not fit neatly into any framework. It could force refinements, revisions, or entirely new interpretations.

And yet, even ambiguous outcomes would matter. Because the blind spot is more than a visual curiosity. It is a natural experiment embedded in every human eye.

Why This Invisible Gap Could Change How We Understand Consciousness

We experience the world as seamless. Continuous. Whole. But beneath that smooth surface lies missing data.

The blind spot is a built-in absence of sensory input. It raises a fundamental question: is consciousness a direct reflection of sensory structure, or is it the product of a predictive model that smooths over imperfections?

If IIT is right, then the structure of neural cause-and-effect relationships shapes the texture of experience itself. The blind spot would leave measurable fingerprints in spatial awareness.

If AI or NREP are right, then consciousness is less about raw structure and more about dynamic modeling. The brain would not merely patch a hole. It would actively construct a stable world, minimizing error and uncertainty.

The implications stretch far beyond vision. They touch the core of how we define conscious experience. Is it something that mirrors the brain’s physical wiring, or something that emerges from predictive engagement with the world?

By examining something as ordinary as a pair of dots, a circle, or a moving curve, this research attempts to probe one of the deepest mysteries in science.

Every time we open our eyes, we trust what we see. But hidden within that trust is a small void, silently filled in by mechanisms we are only beginning to understand.

The blind spot may be tiny. Yet by studying it carefully, scientists hope to illuminate something vast: how the brain creates the feeling of a complete world from incomplete information, and in doing so, bring us closer to understanding the nature of consciousness itself.

Study Details

Clement Abbatecola et al, Protocol for investigating the warping of spatial experience across the blind spot to contrast predictions of the Integrated Information Theory and Predictive Processing accounts of consciousness, PLOS One (2026). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0340593