Xenotransplantation is one of the most emotionally charged and technologically daring frontiers in modern medicine. At its core lies a simple, haunting truth: far more people need organ transplants than there are human organs available. Every day, patients wait, hope, and sometimes die because the gift they need never arrives. Xenotransplantation—the transplantation of organs, tissues, or cells from one species into another—emerged from this crisis not as a science fiction fantasy, but as a desperate, determined scientific response to human suffering.

For decades, the idea of using animal organs in humans felt both inevitable and impossible. Inevitable because biology offers potential donors in abundance, and impossible because the human immune system is exquisitely tuned to reject anything foreign. Yet today, thanks to breakthroughs in genetic engineering, immunology, and biotechnology, pig organs are no longer viewed as crude substitutes but as carefully redesigned biological systems that may one day function safely inside the human body.

The story of xenotransplantation is not just about technology. It is about fear and hope, about the boundaries between species, and about how far humanity is willing to go to save lives.

The Organ Shortage Crisis That Sparked Xenotransplantation

The modern transplant era transformed medicine, turning once-fatal organ failure into a treatable condition. Kidneys, hearts, livers, lungs, and pancreases can now be replaced, restoring years or decades of life. Yet this triumph created a new problem: demand rapidly outpaced supply.

Human organs can only come from donors, living or deceased, and donation rates have never matched medical need. Waiting lists grow longer each year, and the emotional toll is immense. Patients live tethered to machines, restricted by illness, and haunted by uncertainty. Families oscillate between hope and despair, knowing that survival depends on an event they cannot control.

Xenotransplantation arose as a response to this imbalance. If human organs are scarce, scientists asked, could animal organs fill the gap? The question was radical but logical. Animals have long been used in medicine for heart valves, insulin, and other biological products. Why not whole organs?

The answer turned out to be far more complex than anyone imagined.

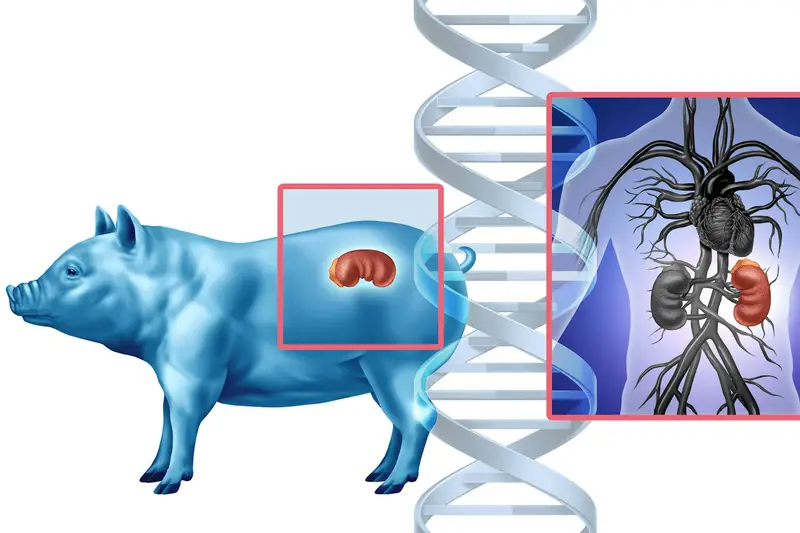

Why Pigs Became the Focus of Xenotransplantation

Early xenotransplantation experiments explored a variety of animals, including primates. While biologically closer to humans, primates posed profound ethical concerns, limited availability, and high risk of disease transmission. Pigs, by contrast, emerged as a surprisingly suitable candidate.

Pig organs are similar in size and function to human organs. Pigs reproduce quickly, are already part of the agricultural system, and can be bred in controlled environments. From a logistical perspective, pigs offered scalability, something essential if xenotransplantation were ever to move beyond rare experiments.

Yet biological similarity alone was not enough. When pig organs were transplanted into primates or humans, rejection occurred almost immediately. The immune system reacted with ferocity, destroying the foreign tissue within minutes or hours. This phenomenon, known as hyperacute rejection, became the central obstacle that defined the field for decades.

The Immune System as the Great Barrier

The human immune system evolved to detect and destroy anything that does not belong. This defense is lifesaving when it comes to infections, but devastating when it comes to transplants. Even human-to-human transplants require lifelong immunosuppression to prevent rejection. Animal organs amplify the problem dramatically.

Pig cells carry molecular markers that humans do not have. Among the most notorious is a sugar molecule found on the surface of pig cells that triggers an immediate immune attack in humans. When human antibodies bind to this molecule, they activate a cascade that clots blood vessels, inflames tissue, and rapidly kills the organ.

This violent rejection once seemed insurmountable. Early xenotransplants failed spectacularly, reinforcing the belief that species barriers were simply too strong. For many years, xenotransplantation hovered on the edge of scientific respectability, pursued by a small group of researchers often met with skepticism.

The turning point came not from transplantation itself, but from advances in genetic technology.

Genetic Engineering and the Rewriting of Pig Biology

The modern revival of xenotransplantation is inseparable from genetic engineering. Instead of trying to suppress the human immune system into tolerating pig organs, scientists began altering pigs themselves, removing the triggers that cause rejection.

By identifying specific genes responsible for producing problematic molecules, researchers learned how to “knock out” those genes, creating pigs whose cells lack the markers that provoke immediate immune attack. This was not a single breakthrough but a gradual accumulation of insights, each one removing another layer of incompatibility.

More recently, gene-editing tools have allowed unprecedented precision. Scientists can now delete, modify, or add genes with remarkable efficiency. Pig organs are no longer biologically wild. They are intentionally redesigned, tailored to coexist within the human body.

Some pigs are engineered to express human proteins that regulate immune responses and blood clotting. These proteins help the transplanted organ communicate with the human immune system, sending signals that reduce inflammation and prevent catastrophic clot formation.

This genetic fine-tuning represents a philosophical shift. Xenotransplantation is no longer about forcing two incompatible systems together. It is about building biological compatibility from the ground up.

Overcoming Rejection Beyond the First Hours

While preventing hyperacute rejection was essential, it was only the beginning. Even when pig organs survived the initial immune assault, slower forms of rejection emerged over days, weeks, and months. The immune system adapted, finding new ways to attack the foreign tissue.

Addressing this required a deeper understanding of immune pathways and a more sophisticated approach to immunosuppression. Modern xenotransplant protocols combine genetic modifications in pigs with targeted drugs that modulate specific immune responses rather than broadly suppressing immunity.

This precision matters. Traditional immunosuppression leaves patients vulnerable to infections and cancer. Xenotransplantation pushes scientists to develop therapies that are more selective, preserving immune defense while protecting the transplanted organ.

The result is a delicate balancing act, one that reflects the complexity of human biology and the ingenuity required to work within it.

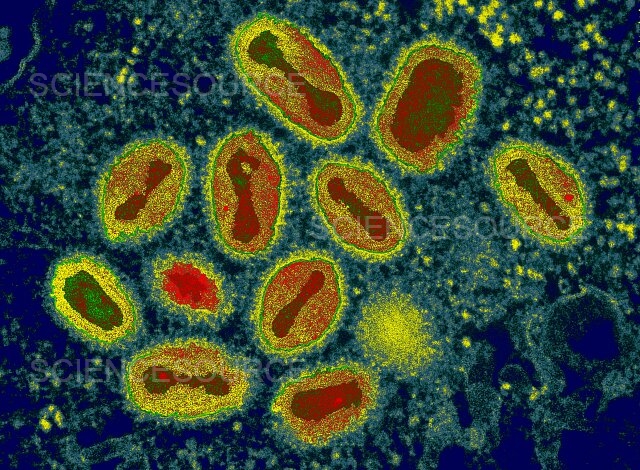

The Hidden Threat of Animal Viruses

Beyond immune rejection, xenotransplantation raised another alarming concern: the risk of transmitting animal viruses to humans. Pigs, like all animals, carry viruses that may be harmless to them but dangerous to humans.

Of particular concern were endogenous viruses embedded in pig DNA. These viral sequences are inherited and cannot be eliminated through standard breeding. The fear was that transplanting pig organs could introduce new infections into humans, potentially creating public health crises.

Addressing this threat required another technological leap. Scientists developed methods to inactivate or remove these viral sequences from pig genomes. Through extensive genetic screening and editing, pigs can now be bred with dramatically reduced viral risk.

Equally important are biosecure breeding environments. Xenotransplant pigs are raised under controlled conditions, monitored continuously for pathogens. This level of oversight exceeds that of most agricultural systems, reflecting the seriousness with which safety concerns are treated.

From Laboratory Success to Human Trials

For years, xenotransplantation advances were demonstrated primarily in non-human primates. Pig organs began to survive longer, function better, and integrate more seamlessly with host physiology. Each incremental success built confidence that human trials were no longer a distant dream.

When pig organs were finally transplanted into humans under carefully controlled circumstances, the world watched closely. These cases were not routine procedures but compassionate-use scenarios involving patients with no other options. The goal was not immediate clinical adoption but learning—understanding how genetically engineered pig organs behave in the human body.

These early experiences revealed both promise and limitation. Pig organs could function, sometimes remarkably well, but challenges remained. Immune responses evolved unpredictably, and long-term outcomes were still uncertain. Yet the mere fact that pig organs could survive and function in humans for meaningful periods marked a historic turning point.

Xenotransplantation had crossed the threshold from theoretical possibility to clinical reality.

The Emotional Landscape of Xenotransplantation

Behind every scientific milestone lies a human story. Xenotransplantation is not an abstract technological achievement; it unfolds in hospital rooms, among families grappling with impossible choices.

Patients who receive experimental xenotransplants often do so knowing the risks are enormous and the outcome uncertain. Their consent is an act of courage, driven by a desire to live and, often, to contribute to knowledge that may save others.

Families face profound emotional complexity. Hope is intertwined with fear, gratitude with anxiety. The idea that a loved one’s life may depend on an animal organ challenges deeply held beliefs about the boundaries between species and the meaning of the human body.

Physicians and scientists, too, carry emotional weight. They stand at the edge of the known, responsible for both innovation and safety. Every decision is scrutinized, not only scientifically but ethically.

Ethical Questions and the Human-Animal Boundary

Xenotransplantation forces society to confront uncomfortable ethical questions. Is it acceptable to genetically engineer animals for human benefit? Does the medical necessity justify the manipulation of life at such a fundamental level?

Pigs used for xenotransplantation are bred specifically for this purpose, under conditions designed to minimize suffering. Yet ethical debate persists, reflecting broader tensions about animal use in science and agriculture.

There are also concerns about equity. If xenotransplantation becomes viable, who will have access? Will it reduce disparities in healthcare, or deepen them? These questions cannot be answered by technology alone. They demand societal reflection and policy engagement.

What distinguishes xenotransplantation ethically is its intent. The goal is not enhancement or convenience, but survival. This does not resolve all moral dilemmas, but it frames the discussion within the context of compassion and necessity.

The Technology Behind Making Pig Organs Human-Compatible

At the technical level, making pig organs safe for humans involves a convergence of disciplines. Genetics, immunology, surgery, and bioinformatics all play essential roles.

Advanced genomic analysis allows scientists to map pig DNA in exquisite detail, identifying sequences that provoke immune responses or harbor viral risk. Gene-editing tools then enable precise modifications, sometimes involving multiple simultaneous edits.

Equally important is organ preservation technology. Pig organs must be harvested, stored, and transplanted in ways that preserve cellular integrity. Advances in perfusion systems, which circulate oxygenated fluids through organs outside the body, have improved organ quality and viability.

Surgical techniques have also evolved. Transplanting pig organs requires adaptations to account for subtle anatomical differences. Surgeons trained in xenotransplantation operate at the intersection of standard practice and experimental innovation.

Learning from Failure and Unexpected Outcomes

Progress in xenotransplantation has not been linear. Each success is accompanied by setbacks, and each failure yields critical insights. Organs that initially function may later fail due to unanticipated immune pathways or physiological mismatches.

Rather than discouraging the field, these challenges have sharpened its focus. Failure is not seen as defeat but as data, revealing where understanding is incomplete and where technology must improve.

This iterative process reflects the nature of scientific progress itself. Xenotransplantation advances not through grand leaps, but through careful refinement, driven by both humility and persistence.

Xenotransplantation and the Future of Transplant Medicine

If xenotransplantation fulfills its promise, it could transform transplant medicine fundamentally. Organs would no longer be scarce, waiting lists could shrink dramatically, and transplants could be planned rather than performed in emergencies.

This predictability would improve outcomes. Patients could be optimized for surgery, organs could be matched more precisely, and the emotional chaos of waiting could be replaced with structured care.

Beyond whole organs, xenotransplantation also holds potential for cellular therapies. Pig cells could be used to treat conditions such as diabetes or liver failure, offering temporary or permanent support.

Yet even as optimism grows, caution remains essential. Long-term safety must be demonstrated, regulatory frameworks must evolve, and public trust must be earned through transparency and rigor.

Public Perception and the Cultural Meaning of Xenotransplantation

Public response to xenotransplantation is shaped as much by emotion as by science. The idea of living with an animal organ evokes fascination, discomfort, and curiosity in equal measure.

Cultural narratives about purity, identity, and the body influence acceptance. Some people embrace the concept as a triumph of ingenuity, while others fear unintended consequences or loss of human distinctiveness.

Communication plays a crucial role here. Xenotransplantation must be explained not as a violation of nature, but as an extension of humanity’s longstanding relationship with biology. Just as vaccines, antibiotics, and prosthetics once seemed unnatural, xenotransplantation challenges existing boundaries that may eventually shift.

A New Relationship Between Species

At its deepest level, xenotransplantation reshapes how humans relate to other species. It forces recognition of biological continuity, the shared molecular machinery that links pigs and people across millions of years of evolution.

This recognition can inspire humility. The fact that a pig’s heart can beat inside a human chest underscores the unity of life, even as it highlights ethical responsibility. Xenotransplantation does not erase differences between species, but it reveals a profound interconnectedness.

In this sense, xenotransplantation is not just a medical innovation. It is a philosophical statement about life, adaptation, and survival in a complex world.

The Road Ahead: Hope Balanced with Responsibility

The future of xenotransplantation will be shaped by ongoing research, ethical oversight, and public dialogue. Scientific optimism must coexist with caution, and innovation must be guided by compassion.

Each new advance brings the field closer to a world where no one dies waiting for an organ. Yet that world will only be realized if safety, equity, and ethics are treated as inseparable from technology.

Xenotransplantation stands as a testament to what humanity can achieve when desperation meets ingenuity. It is a reminder that even in the face of biological barriers that once seemed absolute, understanding and persistence can carve new paths.

In the quiet beating of a pig heart inside a human chest lies a story of survival, sacrifice, and the relentless human refusal to accept death as the final answer.