In the world of cybersecurity, technological defenses often take center stage—firewalls, encryption, intrusion detection systems, and sophisticated algorithms designed to detect and prevent digital threats. Yet despite all these tools, the weakest link in any security system is rarely a machine. It is the human being who operates it. Social engineering is the art of exploiting this human vulnerability. Rather than breaking through firewalls, attackers bypass them entirely by manipulating people into giving up access voluntarily. Understanding social engineering means understanding how human psychology can be turned into a weapon.

Social engineering is not merely a form of hacking; it is a psychological manipulation technique designed to influence behavior and decision-making. It takes advantage of trust, fear, curiosity, urgency, and even empathy—universal human emotions and instincts that can be subtly twisted to serve malicious purposes. Behind every phishing email, fraudulent phone call, or deceptive message lies a deep understanding of how people think, react, and communicate.

To truly grasp how social engineering works, one must look beyond the technical layer of cybersecurity and into the intricacies of the human mind.

The Core Concept of Social Engineering

At its essence, social engineering is the process of deceiving individuals into divulging confidential information, granting access, or performing actions that compromise security. Unlike traditional hacking, which targets computer systems directly, social engineering attacks target people—their perceptions, emotions, and habits. The goal is to manipulate trust and elicit predictable responses.

Social engineering operates on the principle that people are often the path of least resistance in security systems. No matter how secure a network may be, all it takes is one employee clicking on a malicious link, revealing a password, or opening an infected attachment to compromise an entire organization. Attackers know this and craft their strategies accordingly.

The success of social engineering lies in its subtlety. Victims rarely realize they have been manipulated until the damage is done. The attacker creates a believable context—an email from a superior, a message from IT support, or a call from a government representative—and frames it in a way that makes compliance feel natural and logical.

The Human Factor in Cybersecurity

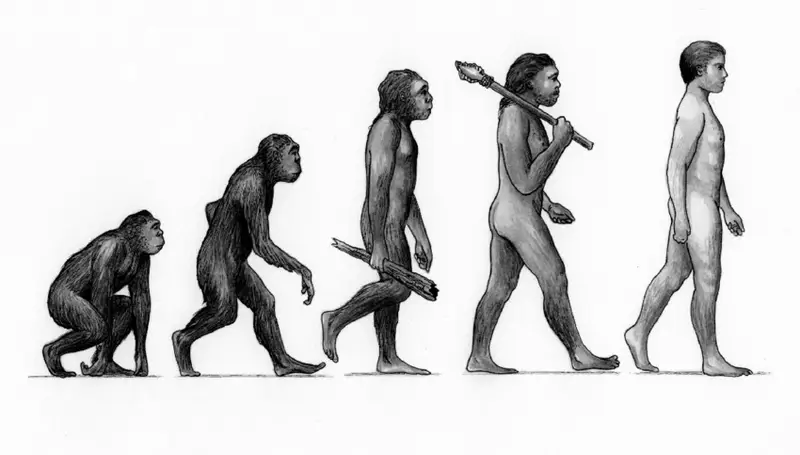

Technology can defend against malware, but it cannot protect against a moment of human error. The human brain evolved to function through social cooperation, not skepticism. Our tendency to trust, to help others, and to seek shortcuts in decision-making creates openings for manipulation. Social engineers exploit this by carefully studying how people respond to authority, reward, and fear.

Humans are also creatures of habit. In workplaces, routines form around communication and workflow. When an attacker introduces a message that fits within this routine—such as a familiar request for credentials or a link to a shared document—it blends seamlessly with the environment. The brain’s reliance on pattern recognition, a mechanism that usually increases efficiency, becomes a liability in the digital age.

Cognitive biases further weaken human defenses. The desire to please superiors, avoid conflict, or act quickly under pressure all lead to decisions that override caution. Even individuals trained in cybersecurity awareness can fall prey to social engineering when the right psychological levers are pulled.

The Psychology of Manipulation

Social engineering is built on psychological principles that have been studied and refined for decades. Attackers use these principles deliberately, crafting messages that tap into subconscious drives and emotional triggers.

The principle of authority is among the most powerful. Humans are conditioned from early life to respect authority figures—teachers, bosses, or officials. When an attacker impersonates someone in a position of authority, the victim’s instinct is to comply without questioning. A simple email signed “CEO” or “HR Department” can override rational skepticism.

Another critical factor is urgency. When people believe that immediate action is required, they are less likely to verify information. A message claiming that an account will be locked in one hour or that a payment must be confirmed immediately triggers panic, pushing recipients to act impulsively.

Scarcity also plays a role. Humans value opportunities that seem rare or limited. Scammers exploit this with messages like “limited-time offer” or “exclusive access,” manipulating recipients into making rushed decisions.

Fear and curiosity are equally potent motivators. A notification about a potential security breach or an intriguing subject line about a personal topic can compel even cautious individuals to click a link or download an attachment. In every case, emotion clouds judgment.

The Anatomy of a Social Engineering Attack

A typical social engineering attack unfolds through several stages. Each stage involves careful planning, observation, and manipulation designed to create trust and extract valuable information.

The process begins with research and reconnaissance. Attackers gather information about their targets—names, job titles, company details, and personal interests—often from publicly available sources such as social media, company websites, or data breaches. This intelligence allows the attacker to tailor their approach, increasing credibility.

The next phase is engagement, where the attacker establishes communication. This may occur via email, phone, text message, or even face-to-face interaction. The goal is to build rapport and create a believable narrative.

Once trust is established, the attacker initiates exploitation. They may request confidential information, send a malicious link, or persuade the victim to perform a harmful action, such as approving a fraudulent transaction or installing software.

Finally, after achieving the objective, the attacker executes the exit strategy, often covering their tracks by deleting messages or erasing evidence. By the time the victim realizes the deception, it is often too late to prevent the damage.

The Art of Impersonation

Impersonation lies at the heart of most social engineering attacks. The attacker assumes an identity that the victim is likely to trust or obey. This could be a coworker, a vendor, a customer support agent, or even a family member.

Digital impersonation is made easier by the abundance of personal data available online. Attackers can study social media posts, company announcements, and leaked databases to craft realistic profiles. For instance, an attacker who knows that an employee recently attended a conference may send an email referencing that event, making the message seem genuine.

Impersonation also extends to technical manipulation. Attackers use spoofed email addresses, cloned websites, and counterfeit phone numbers to make their communication indistinguishable from legitimate sources. In advanced cases, voice synthesis and deepfake technology allow attackers to imitate real voices and faces.

The key to successful impersonation is consistency. Every detail, from language style to timing, must align with the target’s expectations. Social engineers invest time in studying their targets’ communication patterns, ensuring that their messages blend seamlessly into the victim’s environment.

Social Engineering in the Digital Age

As digital communication expands, social engineering has adapted to new platforms. Traditional methods such as email phishing have evolved into a wide range of digital manipulations across social media, messaging apps, and corporate networks.

Social networks offer rich environments for attackers to exploit. Fake profiles, fraudulent friend requests, and deceptive job offers are common tactics. A user might receive a connection request from someone posing as a recruiter or a colleague, only to later be tricked into sharing confidential information.

Messaging platforms have become another battleground. Attackers use WhatsApp, Telegram, or corporate chat tools to send malicious links disguised as shared documents or updates. The informal tone of these platforms often disarms users, making them less cautious.

Even collaboration tools such as Slack or Microsoft Teams have been targeted. Attackers infiltrate internal channels or mimic automated bots to extract sensitive information. The blending of professional and casual communication in digital environments creates fertile ground for manipulation.

The Evolution of Social Engineering Techniques

Social engineering has evolved from simple scams into complex, multi-stage operations. Early attacks relied on generic messages sent to large audiences. Today’s attacks are more refined, leveraging data analytics and automation to customize content for specific targets.

Spear-phishing is a prime example of this evolution. Instead of sending bulk messages, attackers craft individualized emails that reference real events, projects, or colleagues. This level of personalization dramatically increases success rates.

Another advancement is the use of pretexting—creating a fabricated scenario to justify information requests. An attacker might pose as an IT technician needing login details for maintenance, or as a bank employee verifying account activity. The scenario provides a logical framework that makes the request appear legitimate.

Baiting, another form of social engineering, relies on curiosity or greed. Attackers may leave infected USB drives labeled “Confidential” in public areas, knowing that someone will eventually plug one in. Similar tactics occur online, where users are enticed with free downloads or exclusive content that hides malware.

The rise of AI and automation has amplified these techniques. Attackers now use machine learning models to generate realistic messages, replicate writing styles, and even engage in real-time conversations. This fusion of psychology and artificial intelligence represents the next frontier of social engineering.

The Role of Emotions in Social Engineering

At its core, social engineering is emotional manipulation. Every attack aims to provoke a specific emotional response that overrides rational thought. Fear, greed, curiosity, empathy, and urgency are the emotional engines that drive victims to act against their own interests.

Fear is perhaps the most effective motivator. Messages warning of account compromise, unpaid bills, or security breaches trigger panic. Under fear, the brain’s fight-or-flight response activates, narrowing focus and diminishing critical thinking. Attackers exploit this window of vulnerability to push victims toward impulsive actions.

Greed and reward play on the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Offers of refunds, bonuses, or prizes appeal to the desire for gain. Victims lower their guard, convinced they are about to benefit from the interaction.

Empathy is another underappreciated lever. Attackers often pretend to be individuals in distress—a stranded traveler, a sick relative, or a struggling coworker. The human instinct to help others can easily override skepticism.

Finally, urgency creates pressure that prevents deliberation. When time appears limited, people act without verification. Attackers understand this and design their communications to create a false sense of immediacy.

Understanding these emotional triggers is essential for defense. Awareness of how emotions influence decision-making can help individuals pause and evaluate suspicious messages more rationally.

Social Engineering in the Corporate Environment

Organizations are prime targets for social engineering because they house valuable data, financial assets, and operational infrastructure. Attackers exploit both technological and human aspects of corporate life, often starting with low-level employees and working their way up.

Corporate hierarchies inherently create power dynamics that attackers can exploit. A message appearing to come from an executive or department head carries authority, making employees reluctant to question it. Similarly, interdepartmental communication can be manipulated to create confusion or urgency.

Business Email Compromise (BEC) is one of the most financially damaging forms of social engineering. In such attacks, fraudsters impersonate executives or vendors to request wire transfers or sensitive information. These attacks often involve extensive research into corporate structures, communication styles, and financial processes.

Social engineers also target IT departments, knowing that technical personnel have elevated privileges. A convincing pretext—such as a vendor support request or system update—can lead to access being granted to unauthorized individuals.

Insider threats further complicate the picture. Not all social engineering comes from outsiders. Disgruntled employees or contractors can use manipulation to extract data or sabotage systems from within. This blurs the line between external attack and internal vulnerability.

The Interplay Between Social Engineering and Technology

While social engineering focuses on human manipulation, it often intersects with technical exploits. Many attacks combine psychological deception with malware or credential theft. For instance, a phishing email may contain a malicious attachment that installs spyware, while a fake login page captures passwords for later use.

Attackers use technology to enhance credibility. Email spoofing allows them to send messages from forged addresses. Deepfake technology enables voice and video impersonation. Automated scripts send thousands of personalized messages simultaneously, increasing reach without sacrificing believability.

Technology also facilitates persistence. Once an attacker gains access through social engineering, they may install backdoors, create hidden accounts, or plant ransomware. Thus, the human compromise often serves as the first step in a broader technical breach.

This synergy between psychology and technology makes social engineering particularly dangerous. It blurs the boundaries between human and digital vulnerabilities, creating multifaceted threats that are difficult to detect or prevent through technical means alone.

Real-World Consequences of Social Engineering

The impact of social engineering extends far beyond individual victims. On a global scale, it causes billions of dollars in financial losses annually, disrupts business operations, and undermines trust in digital communication.

In 2013, a well-known retail giant suffered a massive data breach after attackers gained network access through a third-party contractor targeted by a phishing email. The breach exposed millions of customer records, demonstrating how one compromised user can endanger an entire ecosystem.

Government agencies have also fallen victim to social engineering. In several cases, espionage operations began with a single deceptive email sent to an unsuspecting employee. Once inside the system, attackers exfiltrated classified data and disrupted operations.

Even personal lives can be upended by social engineering. Victims of romance scams, identity theft, and online fraud experience emotional and financial devastation. The psychological toll of betrayal often lingers long after monetary losses are recovered.

These incidents highlight the far-reaching consequences of human manipulation. Social engineering is not just a technical crime—it is an assault on trust itself.

Defending Against Social Engineering

The most effective defense against social engineering is awareness. While technology can filter threats, it cannot replace human judgment. Individuals and organizations must cultivate a culture of skepticism and verification.

Training programs that simulate real-world attacks can help employees recognize deceptive tactics. The goal is not to create paranoia but to instill caution. Simple habits—verifying unexpected requests, checking sender addresses, and avoiding impulsive actions—can prevent most attacks.

Organizational policies play a crucial role. Multi-factor authentication reduces the damage from stolen credentials. Clear reporting channels encourage employees to report suspicious incidents without fear of punishment. Regular security audits and phishing simulations reinforce vigilance.

Technology complements these efforts. Email authentication protocols, behavioral analytics, and AI-driven threat detection help identify suspicious activity. Yet the human element remains central. Ultimately, the strongest defense is a workforce that understands both the technical and psychological dimensions of security.

The Future of Social Engineering

As technology evolves, social engineering will continue to adapt. The rise of artificial intelligence, deepfakes, and real-time language models will make deception increasingly difficult to detect. Attackers may conduct live conversations using AI personas indistinguishable from real people.

In the coming years, augmented and virtual reality environments may become new frontiers for social engineering. Digital avatars could impersonate colleagues or leaders, creating immersive deceptions that challenge even trained professionals.

Defensive strategies must therefore evolve as well. Future security will depend on cognitive resilience—the ability to recognize manipulation at a psychological level. Educational systems, workplace training, and public awareness campaigns must teach not only technical literacy but also emotional intelligence and critical thinking.

Ethical considerations will also play a role. As AI becomes more capable of generating realistic human behavior, society must confront the question of authenticity in communication. Laws, regulations, and digital verification systems will need to ensure that identity remains trustworthy in a world of synthetic interactions.

Conclusion

Social engineering reveals the profound connection between psychology and cybersecurity. It reminds us that technology alone cannot guarantee safety in a world where human behavior can be influenced, coerced, or deceived. Every phishing email, fraudulent call, or deceptive message is a psychological experiment in manipulation, exploiting instincts that evolved for survival in a far different world than the one we inhabit today.

Understanding social engineering means acknowledging that the battlefield of cybersecurity is as much in the mind as in the machine. Attackers succeed because they understand human nature—our need to trust, to help, and to act quickly. Defending against them requires the same understanding, applied ethically and consciously.

The fight against social engineering is not just a technological challenge but a moral and educational one. It calls for awareness, empathy, and vigilance—the recognition that trust is both our greatest strength and our greatest vulnerability. In the digital age, wisdom lies not in rejecting trust but in managing it carefully, knowing that behind every screen, the human mind remains the ultimate target.