If you’ve ever noticed that some illnesses seem to “favor” men while others strike women more often, you’re not imagining it. Asthma, for example, often shows up earlier in life in men — but as people age, women begin to outnumber men in new asthma diagnoses. Parkinson’s disease disproportionately affects men, while Alzheimer’s disease is more common in women.

And when it comes to autoimmune diseases — illnesses where the immune system turns against the body — the imbalance becomes striking. Women are about two and a half times more likely to develop multiple sclerosis, and a staggering nine times more likely to develop lupus than men.

These trends aren’t just curious medical trivia — they’re clues to something much deeper: the fundamental differences in how male and female immune systems work.

Cracking the Code of Sex-Based Immunity

A groundbreaking new review in Science, authored by scientists at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI), is shedding light on why these disparities exist. Leading the charge are Erica Ollmann Saphire, Ph.D., MBA, President & CEO of LJI, and Sonia Sharma, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Director of LJI’s Center for Sex-Based Differences in the Immune System.

“In just the last two years, LJI scientists have uncovered a whole new body of information about how the immune systems of men and women are very different,” says Saphire. “We’re looking at what is genetically encoded in our XX or XY chromosomes, and how hormones like estrogen and testosterone affect what’s programmed into our immune cells.”

The review dives into three major players shaping immunity:

- Genetics — the XX versus XY blueprint in every cell.

- Sex hormones — chemical messengers like estrogen and testosterone.

- Environmental influences — from diet to chemical exposures to the microbiome.

The X Factor in Immunity

In immunology, “biological sex” refers to the chromosomal pattern — XX in females, XY in males. That extra X chromosome in women turns out to be a game changer.

“The X chromosome has many, many immune-related genes,” explains Saphire. “Women have two copies of each. That gives them, in a sense, twice the palette of colors to paint from in formulating an immune response.”

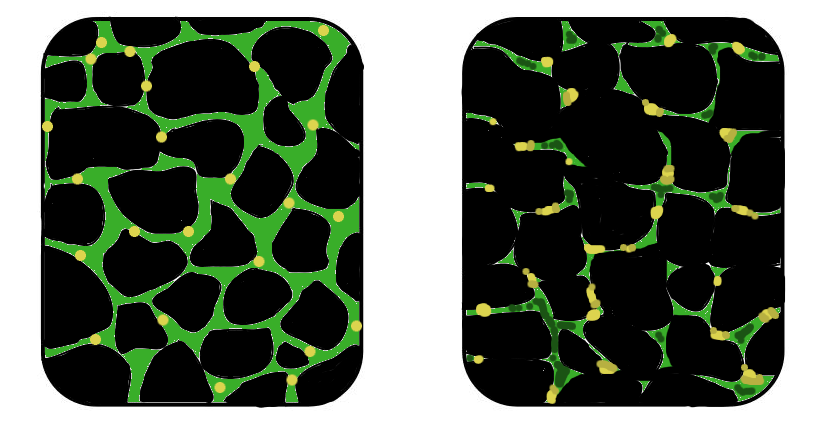

For some genes, both X chromosomes are active at the same time, boosting immune firepower. But there’s a twist — in every female cell, one X chromosome is “switched off” at random. The result is a mosaic of immune cells, each with slightly different genetic settings.

This cellular diversity makes women’s immune systems especially effective at fighting off infections — including viruses like SARS-CoV-2. But there’s a trade-off: that same robust immune response increases the risk of misfires, leading to higher rates of autoimmune disorders.

Hormones as Immune Switches

Sex hormones don’t just regulate reproduction — they act directly on immune cells, influencing which genes are activated or silenced. Estrogen, for example, can enhance certain immune responses, while testosterone can dampen them.

This means that even when a man and a woman have similar immune cells, those cells might behave differently based on hormonal cues. It’s one reason why the same disease can progress more aggressively in one sex than the other.

Beyond Genes and Hormones

Sharma and Saphire emphasize that the story doesn’t stop at chromosomes and hormones. Environmental influences — from nutrition and stress to chemical exposures — shape how the immune system develops and responds. Even the trillions of microbes living in our skin and gut appear to differ between men and women, potentially influencing susceptibility to certain diseases.

These complex interactions also have major implications for cancer treatment. “When it comes to medicine, one size doesn’t fit everybody,” says Sharma. “We’re asking how a person’s individual immune system is contributing to controlling that cancer through immunotherapy.”

A New Era of Precision Medicine

The ultimate goal of this research is not just to understand differences, but to use that knowledge to create better treatments for everyone. By accounting for sex-based immune system variations, scientists hope to design more effective vaccines, tailor cancer immunotherapies, and even develop preventive strategies for autoimmune diseases.

“It takes a team to translate these findings,” says Sharma. “But by understanding the unique strengths and vulnerabilities in each immune system, we can move toward a future where treatments are as individual as the patients themselves.”

More information: Sonia Sharma et al, Sex differences in tissue-specific immunity and immunology, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adx4381